ALSO BY JOHN D. BARROW

Cosmic Imagery:

Key Images in the History of Science

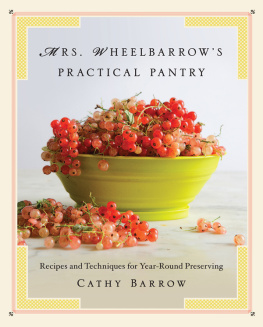

100 Essential Things You Didnt Know You Didnt Know:

Math Explains Your World

The Book of Universes: Exploring the Limits of the Cosmos

Mathletics

100 Amazing Things You Didnt Know about the World of Sports

JOHN D. BARROW

W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

Heck, gold medals, what can you do with them?

Eric Heiden

TO MAHLER

who can already run

and soon will count

Contents

Preface

In this Olympic year I have taken the opportunity to demonstrate some of the unexpected ways in which simple mathematics and science can shed light on what is going on in a wide range of sporting activities. The following chapters will look into the science behind aspects of human movement, systems of scoring, record breaking, Paralympic competition, strength events, drug testing, diving, riding, running, jumping, and throwing. If you are a coach or a competitor, you may get a glimpse of how a mathematical perspective can enrich your understanding of your event. If you are a spectator or commentator, then I hope that you will develop a deeper understanding of what is going on in the pool, gymnasium, or stadium, on the track or on the road. If you are an educator, you will find examples to enliven the teaching of many aspects of science and mathematics, and to broaden the horizons of those who thought that mathematics and sport were no more than a timetable clash. And if you are a mathematician, you will be pleased to discover how essential your expertise is to yet another area of human activity. The collection of examples you are about to read covers a great many sports and tries to pick topics that have not been discussed extensively before. Occasionally, there is a little bit of Olympic history for perspective, but it is balanced by chapters about several non-Olympic sports as well, and if you wish to delve deeper with your reading or push a calculation further there are notes to show you where to begin.

I would like to thank Katherine Ailes, David Alciatore, Philip Aston, Bill Atkinson, Henry Baker, Melissa Bray, James Cranch, Marianne Freiberger, Franz Fuss, John Haigh, Jrg Hensgen, Steve Hewson, Sean Lip, Justin Mullins, Kay Peddle, Stephen Ryan, Jeffrey Shallit, Owen Smith, David Spiegelhalter, Ian Stewart, Will Sulkin, Rachel Thomas, Roger Walker, Peter Weyand, and Peng Zhao for the help, discussions, and useful communications that helped this book come into being. A few of the topics covered here have been presented in lectures at Gresham College in London and as part of the Millennium Mathematics Projects activity for the London 2012 Olympics. I am most grateful to these audiences for their interest, questions, and input. I must also thank family members, Elizabeth, David, Roger, and Louise, for their enthusiasmalthough it turned to disbelief when they realized that this book wasnt going to help them get any Olympic tickets.

John D. Barrow, Cambridge, 2012

How Usain Bolt Could

Break His World Record with No Extra Effort

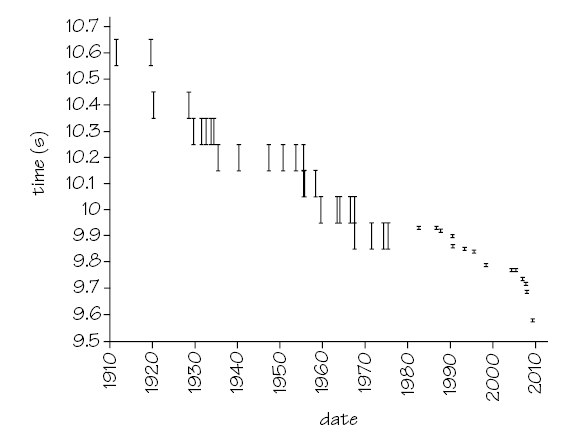

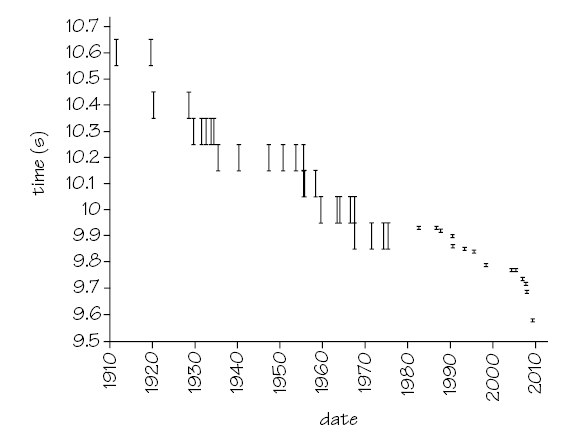

Usain Bolt is the best human sprinter there has ever been. Yet, few would have guessed that he would run so fast over 100 m after he started out running the 400m and 200m races when in his mid teens. His coach decided to shift him down to running the 100m one season so as to improve his basic sprinting speed. No one expected him to shine there. Surely he is too big to be a 100m sprinter? How wrong they were. Instead of shaving the occasional hundredth of a second off the world record, he took big chunks out of it, first reducing Asafa Powells time of 9.74 s down to 9.72 in New York in May 2008, and then down to 9.69 (actually 9.683) at the Beijing Olympics later that year, before dramatically reducing it again to 9.58 (actually 9.578) at the 2009 Berlin World Championships. His progression in the 200m was even more astounding: reducing Michael Johnsons 1996 record of 19.32 s to 19.30 (actually 19.296) in Beijing and then to 19.19 in Berlin. These jumps are so big that people have started to calculate what Bolts maximum possible speed might be. Unfortunately, all the commentators have missed the two key factors that would permit Bolt to run significantly faster without any extra effort or improvement in physical conditioning. How could that be? I hear you ask.

The recorded time of a 100m sprinter is the sum of two parts: the reaction time to the starters gun and the subsequent running time over the 100 m distance. An athlete is judged to have false-started if he reacts by applying foot pressure to the starting blocks within 0.10 s of the start gun firing. Remarkably, Bolt has one of the longest reaction times of leading sprintershe was the second slowest of all the finalists to react in Beijing and third slowest in Berlin when he ran 9.58. Allowing for all this, Bolts average running speed in Beijing was 10.50 m/s and in Berlin (where he reacted faster) it was 10.60 m/s. Bolt is already running faster than the ultimate maximum speed of 10.55 m/s that a team of Stanford human biologists recently predicted for him.

Bolt 0.146 + 9.434 = 9.58

Thompson 0.119 + 9.811 = 9.93

Gay 0.144 + 9.566 = 9.71

Chambers 0.123 + 9.877 = 10.00

Powell 0.134 + 9.706 = 9.84

Burns 0.165 + 9.835 = 10.00

Bailey 0.129 + 9.801 = 9.93

Patton 0.149 +10.191 = 10.34

In the Beijing Olympic final, where Bolts reaction time was 0.165 s for his 9.69 run, the other seven finalists reacted in 0.133, 0.134, 0.142, 0.145, 0.147, 0.165 and 0.169 s.

From these stats it is clear what Bolts weakest point is: he has a very slow reaction to the gun. This is not quite the same as having a slow start. A very tall athlete, with longer limbs and larger inertia, has got more moving to do in order to rise upright from the starting blocks. If Bolt could get his reaction time down to 0.13, which is very good but not exceptional, then he would reduce his 9.58 record run to 9.56. If he could get it down to an outstanding 0.12 he is looking at 9.55 and if he responded as quickly as the rules allow, with 0.1, then 9.53 is the result. And he hasnt had to run any faster!

This is the first key factor that has been missed in assessing Bolts future potential. What are the others? Sprinters are allowed to receive the assistance of a following wind that must not exceed 2 m/s in speed. Many world records have taken advantage of that, and the most suspicious set of world records in sprints and jumps were those set at the Mexico Olympics in 1968, where the wind gauge often seemed to record 2 m/s when a world record was broken. But this is certainly not the case in Bolts record runs. In Berlin his 9.58 s time benefited from only a modest 0.9 m/s tailwind and in Beijing there was no wind, so he has a lot more still to gain from advantageous wind conditions. Many years ago, I worked out how the best 100m times are changed by wind.

All-rounders

Humans are often compared rather unfavorably with the champions of the animal kingdom: cheetahs sprinting faster than the motorway speed limit, ants carrying many times their body weight, squirrels and monkeys performing fantastic feats of aerial gymnastics, seals that swim at superhuman speeds, and birds of prey that can pluck pigeons out of the air without the need for guns. It is easy to feel inadequate. But really we shouldnt. All these stars of the animal kingdom are really nowhere near as impressive athletes as humans. They are very good at very special things, and evolution has honed their ability to dominate their competitors in a very particular niche. We are quite different. We can swim for miles, run a marathon, run 100 m in less than ten seconds, turn a somersault, ride a bike or a horse, high-jump over eight feet, shoot accurately with rifles and bows, throw small objects nearly a hundred meters, ride a bicycle for hundreds of kilometers, row a boat, and lift much more than our body weight over our heads. Our range of physical prowess is exceptional. Its easy to forget that no other living creature can match us for the diversity of our physical abilities. We are the greatest multi-eventers on earth.

Next page