Part I. Introduction

The Macintosh and Windows are the most popular computer platforms on Earth. But the relationship between them, and between the people who use them, has never been smooth. For years, Macintosh fans felt robbed by Microsoft, who, they felt, stole the best features of the Macintosh when designing Windows. And Windows users, for their part, often resented what they perceived as the excessive enthusiasm Macintosh fans felt for their underdog platform.

Today, much of the anger has subsided. Microsoft, it turns out, is enthusiastic in its support of the Mac OS, happy to support its sole competitor (if only to show the U.S. Justice Department that Microsoft is no monopoly). The Macintosh, moreover, benefits greatly by Microsofts Macintosh software division, whose Office suite and Internet tools rank among the most popular Macintosh applications. Meanwhile, Apple has helped itself to some of the best ideas from Windows in the latest versions of the Mac OS, bringing the two systems even closer together.

Bilingual Education

As a result, we now live in an era of unprecedented shifts from one operating system to another. During Apples financial slump of 1995 to 1997, thousands of Macintosh fans reluctantly started using Windows out of a fear that their favorite computer maker might not be around to support the Macintosh for long. Then, during Apples subsequent recovery, thousands of frustrated Windows users embraced the simplicity and style of Apples smash-hit iMac computer. Its increasingly common for someone to use a Macintosh at home, but Windows at work; Windows in Accounting, but a Macintosh in the art department; Macs for the kids, Windows for their parents. And among computing professionalsnetwork administrators, consultants, and web page designersfamiliarity with both platforms is becoming ever more important.

With all the emotion clearing like smoke, one fact becomes clear: whether at Apple or Microsoft, the designers of an operating system must solve the same set of challenges. They need to offer you, the user, a means of interacting with your files and folders, access to preference settings to tailor the operating system to your purposes, a system of printing and going online, and so on. Sometimes Apple and Microsoft solved these puzzles in similar fashions, other times they took drastically different approaches, but the problems themselves are the same. Once you study both platforms, the parallels become crystal clear: a Macintosh alias is essentially identical to a Windows shortcut; the Macs Trash can matches the Windows Recycle Bin; the Macs Network Browser and the Windows Network Neighborhood both access other computers on your network; and so on.

But knowing one set of terminology isnt much help in figuring out the other. Who would guess that a shortcut and an alias have the same function? And more important, when youre plopped in front of the platform you dont know, how can you figure out the important differences between aliases and shortcuts?

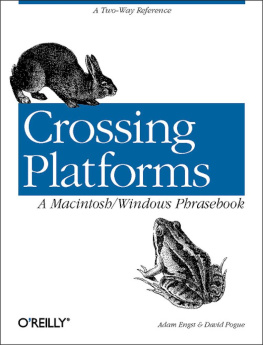

This book is the answer. Its designed like a foreign-language translation dictionary. For instance, if youre a Macintosh user trying to use a Windows machine and you want to create an alias, you look up alias to find out its a shortcut in Windows. Like a French-English/English-French phrasebook, this one is split in half; one set of alphabetical entries is written for the person whos switching to Windows, and the other set is written for people going to Macintosh.

How to Use This Book

Crossing Platforms assumes that you already know your native computer; it makes no attempt to start from such basics as pointing, clicking, or how RAM and hard disks work. Its mission is to make you operational on the less familiar platform as efficiently as possible, to help minimize your groping for important controls in an unfamiliar vehicle.

The key to using this book is simple: Turn to the appropriate half of the bookFor Mac Users Learning Windows or For Windows Users Learning the Mac. Then look up the term you already know.

If youre a Macintosh user, then, use this half of the book. Look up such Macintosh-specific terms as alias, Disk First Aid , and Option key , or generic computing terms like file sharing, moving files , and printing files . Either way, youll find out exactly what the equivalent component is in Windows, and you can read about how it differs from the one you already know. Words in boldface are cross-referencesother related terms in this same half of the book that you can look up.

As you become increasingly familiar with Windows, youll likely recognize more and more familiar landmarks. Eventually, youll grasp the stylistic differences of the worlds two most famous system software companies, and maybe youll even anticipate where Microsoft stashed things. At that point, you wont need this book as often, and youll have attained a most impressive statusas a truly bilingual computer user. When that time comes, you wont even bat an eye when taking what was once an inconceivable leap: crossing platforms.

Operating System Versions

Both Apple and Microsoft update their operating systems constantly. This book covers the most widely used, recent versions of each: Windows 95 and 98, and Mac OS 8 through 8.6. The book doesnt explicitly cover Windows 2000, but almost all of this books Windows discussions should apply equally well to the newer Windows.

The Ten Most Important Windows Differences

This entire book is dedicated to documenting the differences between the Mac OS and Windows. But if today is your first day in front of a Windows PC, here are the ten differences most likely to trip you up.

Turning the machine on and off. Theres no keyboard on/off button on the PC, as there is on every Macintosh. Instead, your PC probably has a power button on the front panel; push it to turn on the computer. To shut down, choose Shut Down from the Start menu at the lower-left corner of the Windows screen.

Mouse buttons and contextual menus. The Windows mouse has two buttons instead of one. Use the left button for everyday clicking. Use the right mouse button where you would Control-click something on the Macintoshthat is, to bring up contextual pop-up menus.

Menu bars. In Windows, a separate menu bar appears at the top of every single window. Theres no single menu bar at the top of the screen, as on the Macintosh.

Keyboard shortcuts. Many keyboard shortcuts are the same in Windows as on the Macintoshbut you should substitute the Ctrl key for the Command key, and the Alt key for the Option key.