An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data is available.

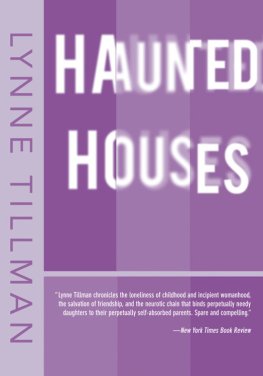

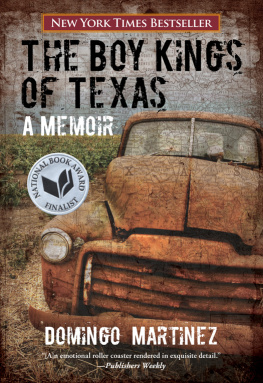

The Building at 805 East Tyler Street

(Photo by Brad Doherty)

CHAPTER 1

An Unmeasured Feeling

Its a long story here.

MINERVA PEREZ, NEIGHBOR

M idway through my first year as a newspaper reporter, I walked through a two-story apartment building in Brownsville, Texas, where a poor young couple had murdered their three children. My assignment was to write about the local debate as to whether the decrepit but historic building should be demolished. It sat on a corner on the outskirts of Brownsvilles downtown, just a handful of city blocks from Mexico. There, tropical birds effortlessly crossed into the United States from points south, while human travelers traversed international bridges or paid coyotes to hustle them surreptitiously across the Rio Grande. Yet, even among the quotidian dramas of the border, the deaths of Julissa, John Stephan, and Mary Jane were not merely reportedthey were communally grieved.

When I interviewed people about the murders, some cautioned that the crime was a black hole that held nothing within. Heinous crimes are like that, people said. They do not teach lessons, they only confirm the worst suspicions about what can happen in our world. To venture close to an entity so dark and try to wrest value from its depths was not only foolish, it was dangerous: a black hole withholds and mangles all it consumes and devours anything wandering too close to its invisible mouth. Yet, the same people who compassionately issued this warning also told me, often at length, of all the crime had come to mean in their lives, how it had challenged their beliefs or fortified them. How it continued to flicker as a figure on the edge of their peripheral vision, moving out of range when they turned to see it head-on.

That the victims were children, that the father was from Brownsville, that an explanation seemed always out of reach, had caused people to question their understanding of their community, their spirituality, the values they held as universal. As they reckoned with these questions, they necessarily reconfigured the world around the shape of the crime in its wake.

As I began to visit the building with increasing frequency, I noted a cloud hovering overheadan accumulation of meaning more dense and persistent than Id ever intuited. It signaled that there was more to this story than the simple details, the dates and quotes and analysis that a reporter usually assembles. The cloud was heavy with palpable ambivalence, an existential dread about what had happened here and how it had burrowed through and ruptured the landscape, leaving damage that had yet to be completely measured. I began to realize that, if I wanted to comprehend this city, a place layered with unwritten history that seemed to lie naked and obscured in the same instant, this story was key.

I had never before been drawn to tragic crimes. Like many people, I pushed them out of mind when I could. It was easier to box them up and store them on a mental shelf of humanitys worst moments. Media cover these stories for a while, until the case is closed and the criminal is punished. Then, more often than not, the stories retreat into the background, at least on a national level. For the cities that survive them, what changes? Something must change, even if the difference is unnoticeable on the surface. People continue with their lives, having families and teaching their kids. They fall in love and break up. They get degrees and jobs and build new homes. As for the criminals, I figured they still eat and sleep and talk and think.

John Allen Rubio, the father of the children, had become an infamous figure in Brownsville, known by all three of his names. He was both a product of the city, born and raised, and seemingly its communal enemy, guilty of an act almost too terrible to make sense of. He pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, lost, and was sentenced to die. After winning an appeal, his second trial took place seven years after the crime. Again, he was convicted and was given the death penalty.

When I started writing to John, I didnt expect him to respond. But he wrote to me for years. He told me about his childhood, his depression, and the three children who died that night and early morning. I never fully got used to those envelopes from the Polunsky Unit, sitting alongside the bills and catalogs in our mailbox. Johns answers to my questions were candid and conversational in a way I found captivating. He was a confessed killer, but his personality leaped from the pages, undeniably human, full of ideas and memories. In my minds eye, I could see the curtain at the edge of the proscenium being tugged away. A construct of this mans life had been built by headlines and court documents, but it was complicated, predictably, by his reflections, his language, his version of that life.

After that first tour, I fell into the buildings orbit. Id drive by on my way home from work and pause for a long moment at the stop sign out front. Later, I would park and walk around the perimeter slowly, cataloging its every corner and blemish and frailty. The cloud lingered here, whether the sky was dense with fog or crisp and blue. Someday, John and the building would be banished from the earth. It felt as if everything were disappearing, or about to, until all that would be left was a sad story with no meaning.

There had to be meaning; it hung morosely overhead. I could feel it following me, leaving a damp film on my skin when I got home.

I began to compile evidence about what had happened on East Tyler Street and its aftermath and sort through it. The collection came to include more than just the testimony and confessions from the murder case. Much of what I considered evidence was tangential: a house where John lived as a boy, the moral claims of the district attorney who prosecuted the case, the arguments made by people in the neighborhood for why the building should be destroyed. Confounding questions emerged, ones Id never before considered, which couldnt be resolved by searching a database or conducting a few interviews. Like the algorithm marked in chalk on a mathematicians blackboard, or the brew in a cauldron, it seemed that if the correct elements were fused, they would deliver the answers.