Also by Len Fisher

How to Dunk a Doughnut:

The Science of Everyday Life

Copyright 2004, 2011 by Len Fisher

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

The Common Cormorant by Christopher Isherwood is quoted by the kind permission of Don Bachardy and the Christopher Isherwood estate.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-538-0

For my father, with fond memories,

and my wife Wendella, with love

Contents

Index

Preface

All truth passes through three stages: First, it is ridiculed; Second, it is violently opposed; and Third, it is accepted as self-evident.

Arthur Schopenhauer

T his book tells the stories of scientists whose ideas appeared bizarre, peculiar, or downright nutty to their contemporaries but who stuck to their guns through ridicule, oppression, and persecution. Some of their ideas were nutty, and most of these ideas (though by no means all!) rapidly became extinct. Other concepts, seemingly every bit as bizarre, passed every test that could be thrown at them and survived to be accepted and used by scientists such as myself as part of our everyday work.

The ideas that scientists now use routinely can still seem ridiculous to people outside science. My wife certainly thought so when she came home one evening to find me riding her bicycle down the road with the wheel nuts removed, explaining to a radio interviewer that the counterintuitive physical laws discovered by Galileo and Newton predicted that the wheels would stay on. Her brief, pungent comment about scientists and their lack of common sense was duly recorded and broadcast on national radio.

My wife was right; science and common sense often dont mix. Its not the scientists fault; Nature is the principal culprit. Those who proposed bizarre-sounding ideas about its behavior were often forced to do so after recognizing that the accepted wisdom, or common sense, of their eras was simply insufficient to understand what was going on. Their contemporaries, with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, were not always as receptive to new ideas as the popular image of the dispassionate, rational scientist would have us believe, and the fates of those who advanced new ideas ranged from the loss of their jobs to the loss of their lives. Their histories belie the popular image of science as an orderly, logical progression. It is more like a procession, with leaders and followers, which is unwillingly forced to change direction each time it comes up against the barrier of a revolutionary new idea. This book traces the route of the procession through the stories of those who forced the changes and shows how many of their ideas, which seemed to be so at odds with the common sense of the time, are now used by scientists to understand and tackle everyday problems. It also reveals the true process of discovery, where the brilliant has often met the bizarre and only the wisdom of hindsight allows us to distinguish between the two. The message is that we need to allow for a certain amount of laughable nuttiness if we are not to lose genuinely original insights and developments. If we cant tell the difference between oddity and insight, then maybe its wise not to laugh too loud.

A Note on the Approach of This Book

I am a scientist, not a historian, and when I write about scientists from earlier times it is from my perspective as a scientist. In consulting copies of original diaries, papers, and notes, I have often found I was reading about people who thought in the same way that modern scientists do but who happened to be working with a different set of questions and in a different environment of belief about the way in which the world works. I was particularly struck to discover the parallels between their struggles to understand how Nature works and my own efforts (rather less successful) as a child to understand for myself everything from movement, studied by Galileo, to light, space, and time, elucidated by Einstein. I have included some tales from this part of my life, partly to show that thinking like a child isnt necessarily a bad thing when it comes to science, and mainly to show that you dont have to be a genius to understand science it just needs persistence, and the wish to know.

A Note on the Notes

The notes section in many books is stuffed with boring detail. The notes at the back of this book are different, stuffed with interesting detail and designed to be read independently of the main text. Here you will find unusual, bizarre, and occasionally salacious tidbits, as well as the extra detail and expanded explanations that were too interesting to leave out but which I couldnt fit into the main stories without breaking the flow.

Whether you choose to read the book from the front or the back, its main purpose is still to reveal how science really works, both in the laboratory and in the wider world, and to show that scientists are just as human as anyone else.

Acknowledgments

M y wife, Wendella, has been a consistent source of strength and support and has read every chapter from the point of view of a nonscientist. Her amazing ability to spot flaws and obfuscations and to suggest ways of correcting them has added greatly to the ultimate clarity and readability of the book.

My agent, Barbara Levy, has been an enthusiastic proponent from the start, as have my editors, Cal Barksdale and Tom Wharton, whose professional insights have been particularly helpful in maintaining the pace and focus of the story lines. Many of my academic colleagues and other friends have also helped, some in conversation, some by providing material, and others by reading sections of the manuscript with critical and expert eyes that have (I hope) kept me from drifting too far away from the straight and narrow. Among those to whom I owe a particular debt of gratitude are (in alphabetical order) Lindsay Aitkin, Don Bachardy, Peter Barry, Susan Blackmore, Garry Graham, Denis Haydon, Oliver Heavens, Rod Home, Frank James, Jane Maienschein, Jeff Odell, Alan Parker, Larry Principe, Klaus Sander, John Smith, Brian Stableford, Jennifer Woodruff Tait, Phil Vardy, Jeff Watkins, Keith Williams, and Joe Wolfe. Unfortunately, I cannot blame them for any mistakes that remain. It is also the way of such lists that there will be at least one person who has made an important contribution but whose name I have inadvertently omitted. To that person I apologize, with the promise of a drink next time we meet and a correction if this book should run to a second edition.

1

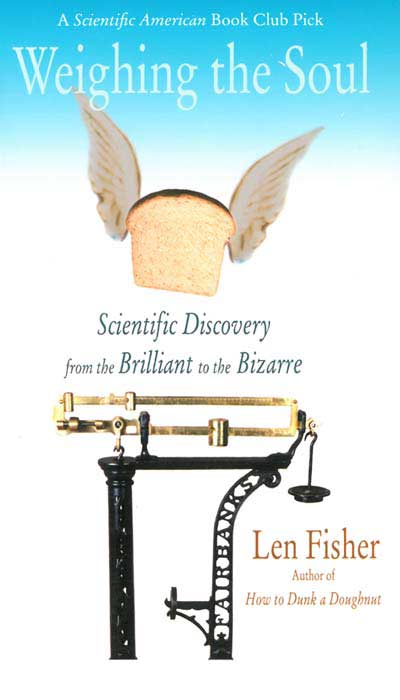

Weighing the Soul