METAMORPHOSES

OVID

METAMORPHOSES

TRANSLATED AND WITH NOTES BY

CHARLES MARTIN

INTRODUCTION BY BERNARD KNOX

W.W.NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON The Introduction by Bernard Knox previously appeared in The New York Review of

Books , with the exception of the final paragraph. Reprinted with kind permission of

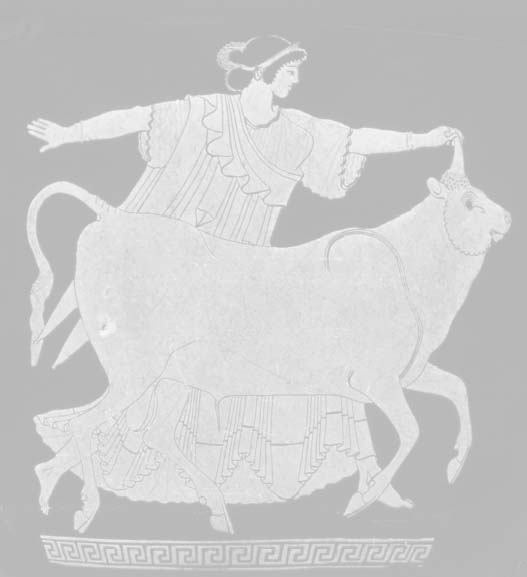

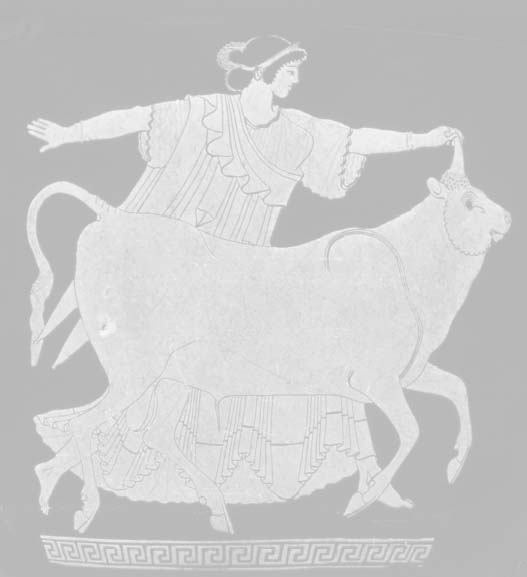

The New York Review of Books . Copyright 2004 by Charles Martin Detail of Grecian vase depicting the kidnapping of Europa by Jupiter disguised as a bull, ca. 470 A.D. Christel Gerstenberg/CORBIS. All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W.W.

Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 Production manager: Amanda Morrison Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ovid, 43 B.C .-17 or 18 A.D .

[Metamorphoses. English]

Metamorphoses / Ovid; translated by Charles Martin.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 978-0-393-07243-3 1. Fables, LatinTranslations into English. 2.

MetamorphosisMythologyPoetry.

3. Mythology, ClassicalPoetry. I. Martin, Charles, 1942II. Title.

PA6522.M2M44 2004

873'.01dc22 2003014491 W.W. 10110

www.wwnorton.com W.W. 10110

www.wwnorton.com W.W.

Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT TO JOHANNA

CONTENTS

BOOK I

THE SHAPING OF CHANGES BOOK II

OF MORTAL CHILDREN AND IMMORTAL LUSTS BOOK III

THE WRATH OF JUNO BOOK IV

SPINNING YARNS AND WEAVING TALES BOOK V

CONTESTS OF ARMS AND SONG BOOK VI

OF PRAISE AND PUNISHMENT BOOK VII

OF THE TIES THAT BIND BOOK VIII

IMPIOUS ACTS AND EXEMPLARY LIVES BOOK IX

DESIRE, DECEIT, AND DIFFICULT DELIVERIES BOOK X

THE SONGS OF ORPHEUS BOOK XI

ROME BEGINS AT TROY BOOK XII

AROUND AND ABOUT THE ILIAD BOOK XIII

SPOILS OF WAR AND PANGS OF LOVE BOOK XIV

AROUND AND ABOUT WITH AENEAS BOOK XV

PROPHETIC ACTS AND VISIONARY DREAMS

Publius Ovidius Naso was distrusted in the nineteenth century as an immoralist and dismissed for most of the twentieth as a lightweight, but is now back in favor. He was all the fashion in his own time, too, and that time has some intriguing resemblances to our own. It was an age of peace that succeeded generations of war and also one that saw the obsolescence of the stern moral code that had made the early Roman republic a nation of dedicated farmer-soldiers and faithful, fertile wives. In Ovids day divorce had become commonplace in upper-class Roman circles, abortion not infrequent, families small, and adultery generally condoned. Ovid, who proclaimed himself the well-known recorder of his own amorous follies, justified that title by devoting well over two thousand lines of elegiac couplets (the standard meter of Latin love poetry) to a witty chronicle of the ups and downs of his long affair with a married woman, including her abortion and his seduction of her maid. Not content with this he went on to write The Art of Love , an instruction book for young men on where in Rome to find women and how to seduce them, in which at one point he announced his satisfaction with the age in which he lived.

Let others delight in the good old days; I am delighted to be alive right now, This age is suited to my way of life. The word here roughly translated as way of life moribus is, as so often in Ovid, a significant allusion. It is an unmistakable and mocking echo of a famous line of Ennius, the epic poet who, two centuries earlier, had celebrated the great days of the early republic, the wars against Carthage, and the conquest of the eastern Mediterranean: Moribus antiquis res stat Romana virisque By its ancient way of life and its men the Roman state stands firm. Ovid goes on to make perfectly clear why he is so happy to be living now. It is not because of the stubborn gold we mine, or the rare shells gathered/For our delight from foreign shores,/but for/Refinement and culture, which have banished the tasteless/Crudities of our ancestors. U NFORTUNATELY FOR O VID , Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, who in 30 B.C ., after the defeat and death of Antony and Cleopatra, had become the master of the Roman world, was intent on turning the clock back.

Using powers granted him by a subservient Senate, he established a whole legislative program designed to restore the old Roman family values. Octavian himself, before he assumed the titles of Augustus and pater patriae , had been no plaster saint. He had divorced his wife, Scribonia, to marry Livia while she was still pregnant by her divorced husband, and, according to Suetonius, he had even before that had a remarkable career as a libertine. He was also the author of a six-line epigram abusing Antony and his wife Fulvia so explicitly obscene that Martial (who quotes it in full)cites Augustus as his precedent for his own witty little books stuffed with epigrams that Byron labeled nauseous. But there is no moral reformer more fanatical than a reformed rake, and these severe laws, though not always strictly enforced, were there on the books to be used if needed. One of them made adultery a crime punishable by expulsion from Rome; another restricted advancement on the administrative-military ladder to high office, the cursus honorum , to married men with three children.

Augustus must have been infuriated by the popularity of poems that, as Peter Green puts it, presented adultery as a high-class social game,but it was not until 8 A.D . that he took action, not just expelling Ovid from Rome but sending him all the way to Tomi on the Black Sea, a Fort Apache of the Roman frontier, where, according to Ovid, showers of poisoned arrows could come over the walls at any moment. One of the two reasons for this harsh sentence, Ovid informs us in one of the many poems written in exile, was a poempresumably The Art of Love which, however, he defends in a long letter addressed to Augustus as no worse than the love elegies written by Tibullus and Propertius or for that matter than Virgils Aeneid , in which Aeneas, the ancestor of Romes founder, joins in illicit union with Dido. The other reason he gives for his punishment is an error , a word with a semantic range stretching from mistake to madness whatever he did (or failed to do) probably had some connection with the many court intrigues sparked by the vexed problem of the succession to Augustus or with the sexual scandal that resulted in the exile of Augustus daughter Julia. The Art of Love had been in circulation for some eight years when Ovid was forced to leave Rome. In those years he worked on two long poems.

One of them was the Fasti , a celebration of the recurring religious fesitvals of the Roman calendar and the myths connected with them. But this was not the only poem Ovid worked at in the years before the imperial edict consigned this playboy of the Roman World to the outer darkness of the frontier. He also produced a major work which, he announced in its closing lines, was his warrant for eternal fame: Wherever Roman power rules over conquered lands I shall be read, and through all centuries, if poets prophecies speak truth, I shall live. The poem was known by the title Metamorphoses ,a Greek word meaning changes of shape its opening lines proclaim its themeMy mind is intent on singing of shapes changed into new bodies. In the Metamorphoses , by far the most ambitious of his poems (and also the longestover 12,000 lines divided into fifteen books), he abandoned the elegiac couplet, the metrical form used in all his other extant work. For the Metamorphoses he chose the hexameter, the line in which Homer sang of the wrath of Achilles and the wanderings of Odysseus, which Ennius adapted for the Latin language in his celebration of the great wars of the early republic, and Virgil shaped to majestic music for his tale of Aeneas and the origins of Rome.

OVID

OVID