written in Rome some time between 25 and 16 BC , was once his most popular work. The title translates as

. It is a series of poems in the voices of women from Greek and Roman myth including Phaedra, Medea, Penelope and Ariadne addressed to the men they love. Claimed as both the first book of dramatic monologues and the first of epistolary fiction,

is also a radical text in its literary transvestism, and in presenting the same story from often very different, subjective perspectives. For a long time it was Ovids most influential work, loved by Chaucer, Dante, Marlowe, Shakespeare and Donne, and translated by Dryden and Pope. Clare Pollards new translation rediscovers Ovids

for the 21st century, with a cast of women who are brave, bitchy, sexy, suicidal, horrifying, heartbreaking and surprisingly modern.

In many ways Pollard, a wunderkind who wrote her first poetry collec-tion while still at school, is a good match for the equally precocious Ovidthese are lively versions, seasoned with both agony and irony, reanimating Ovids originals

JOSEPHINE BALMER , The Times Ovid died in exile, booted out of Rome for what he described as carmen et error a poem and a mistake. These letters remind us that he, of all Latin love poets, understood the plight of the person left behind, waiting for news. He knew that even bad news was less excruciating than no news. And this breezy, witty translation should give new readers the chance to share this understanding

NATALIE HAYNES , The Guardian COVER PHOTOGRAPH Lee Miller, in Jean Cocteaus film The Blood of a Poet by Man Ray (1930)

Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, BI, Paris 2013

with kind permission from M. Pierre Berg, prsident of the Comit Jean Cocteau For Matthew

I

When I was working on this new version of Ovids

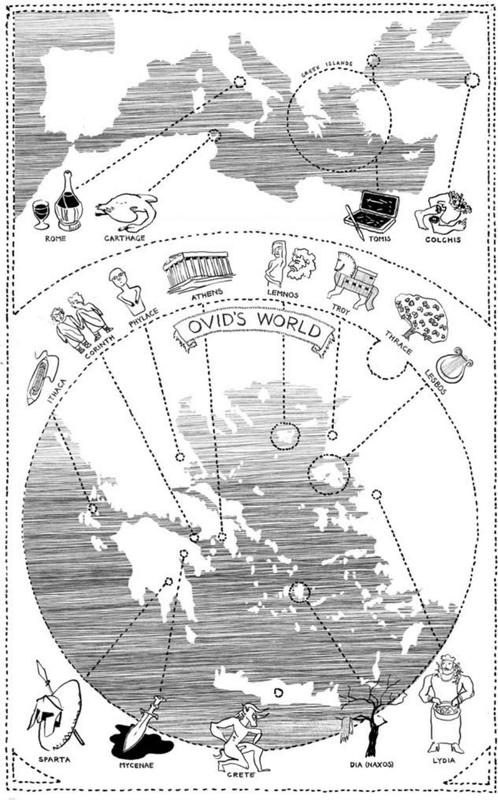

Heroides, I was invited with my husband to the island of Santorini for the wedding of some friends. We flew into Athens to get the boat, and also spent a few days on Amorgos.

I took Richard Lattimores translation of The Iliad to read on the vast ferries as they churned past schools of dolphins. It was a wonderful trip. The wedding was outside, in a whitewashed courtyard, and then we feasted and danced under the moon, drinking glasses of the golden local wine. We visited a volcano, bathed in belching sulphur pools, and then were schlepped up a hill by donkeys. The sea was the most clear and pale-green I have ever seen. One day we swam to a beach through a narrow, glowing cave; on another we saw a fat, black eel.

On Amorgos there were white villages with windmills; rocky outcrops that smelt of wild thyme. The ferries, though, were a nightmare. The distances between the islands were much further than Id imagined, and there were strikes. No one knew when they were going to go. Hours were spent on the phone, on hold to travel agents, hearing conflicting stories, or else sat waiting on the boiling concrete docks. As another ferry left without us on it and, perched on my backpack, I read of Homers baleful battle between godlike men, I would think of the women they had left behind.

Often just-married, they had been immediately abandoned, and left standing on the beaches, or the cliffs, or the harbour, watching their men go off to Troy. Grieving. Impotent. Stuck, stuck, stuck.

II

The year before, coincidentally, I had been in Rome for another wedding (I was thirty and going to a lot of weddings), reading the

Heroides for the first time. I always try to pick my reading matter to match my location, and I had with me Ovids

The Art of Love, translated by James Michie, as well as a battered old copy of George Showermans 1914 Loeb translation of the

Heroides, borrowed from a library.

The only Ovid I had read before was Ted Hughes version of the Metamorphoses, and so I was surprised and charmed by James Michies rendering of Ovids voice in The Art of Love how dry and modern it was. Born in 43 BC , Ovid was sent to Rome as a boy to study, and lived in the city until Augustus sent him into exile in 8 AD to Tomis by the Black Sea (for what seems to have been his involvement or complicity in some scandal, although historians have never quite solved the mystery). For most of his life, Ovid was very much a Roman poet, so I could almost glimpse him as I strolled through the Forum or by the Circus Maximus (as he noted, at the Circus you could: sit as close to a girl as you please, /so make the most of touching thighs and knees). Then I started to read the Heroides, and as I began to realise what it actually was a retelling of the Greek myths from the perspective of the women (Phaedra was there, and Medea, and Penelope) I got a feverish, vertigo-feeling. That mixture of excitement and panic every writer feels when they have a brilliant idea. The prose translation had dated, but behind the archaisms I could glimpse something astonishing.

I had to write a new version of this! How had I never heard of this book before? The wedding ceremony was Catholic and in Latin impenetrable to me, of course, my state school in Bolton not teaching the classics, but I did not let this detail put me off my new project. The party afterwards was on a nearby beach. This is life, I thought to myself, prosecco in hand, as candles wobbled in the sea breeze and the newlyweds gazed at each other. Its about love. And this, it seems to me, is why the Heroides is a great book. It takes huge narratives of nationhood, war, death, myth and religion, but it puts love at the centre.

Because it may sound a little cheesy but in the end love, for most of us, is what matters. (Im at a wedding, drinking prosecco, okay? Such observations are allowed.)

III

Yet the sober truth is that for this reason the

Heroides has often been dismissed. By putting love at its heart, it has been seen as trivialising and domesticating great legends, with the criticism often smacking slightly of misogyny the critic Brooks Otis talks of: the wearisome complaint of the reft maiden, the monotonous iteration of her woes, whilst Howard Jacobson moans of grating and carping women. Irritatingly, whenever the heroines do show strength and humour, this is also condemned. L.P. Wilkinson sneeringly notes that: The heroines are not too miserable to make puns.

The implication is that any wit in the voices is just Ovid showing his face through the mask, unable to sustain character. Because, obviously, women are never ironic. Heroides is a radical collection of poems. It is a daring act of literary transvestism. It is an attempt to modernise and revitalise well-worn myths. Its narrators stories are deeply subjective, partial and often unreliable, with this highlighted by telling the same stories from different perspectives.

It has been called both the first book of dramatic monologues and the first of epistolary fiction. For a long time, it was Ovids most loved and influential text, its impact visible in Chaucers The Legend of the Good Women, Dante, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Donne. It was translated by Dryden and Pope Yet on the dispiriting days I spent in the British Library trawling essays about the Heroides, it seemed like Id made a mistake and was wasting my time on a minor text. Mean-spirited critics repeatedly talked of Ovids failure or his manipulative presence usually proving their points with their own flat-footed translations with Florence Verducci claiming that even the most closely reasoned and dispassionate argument for the poetic merit of Ovids collection will whisper of the marketplace, the boutique for overpriced and at best second-rate antiquities. This is OVID! I wanted to shout. Hes simultaneously inventing about four genres! Have some