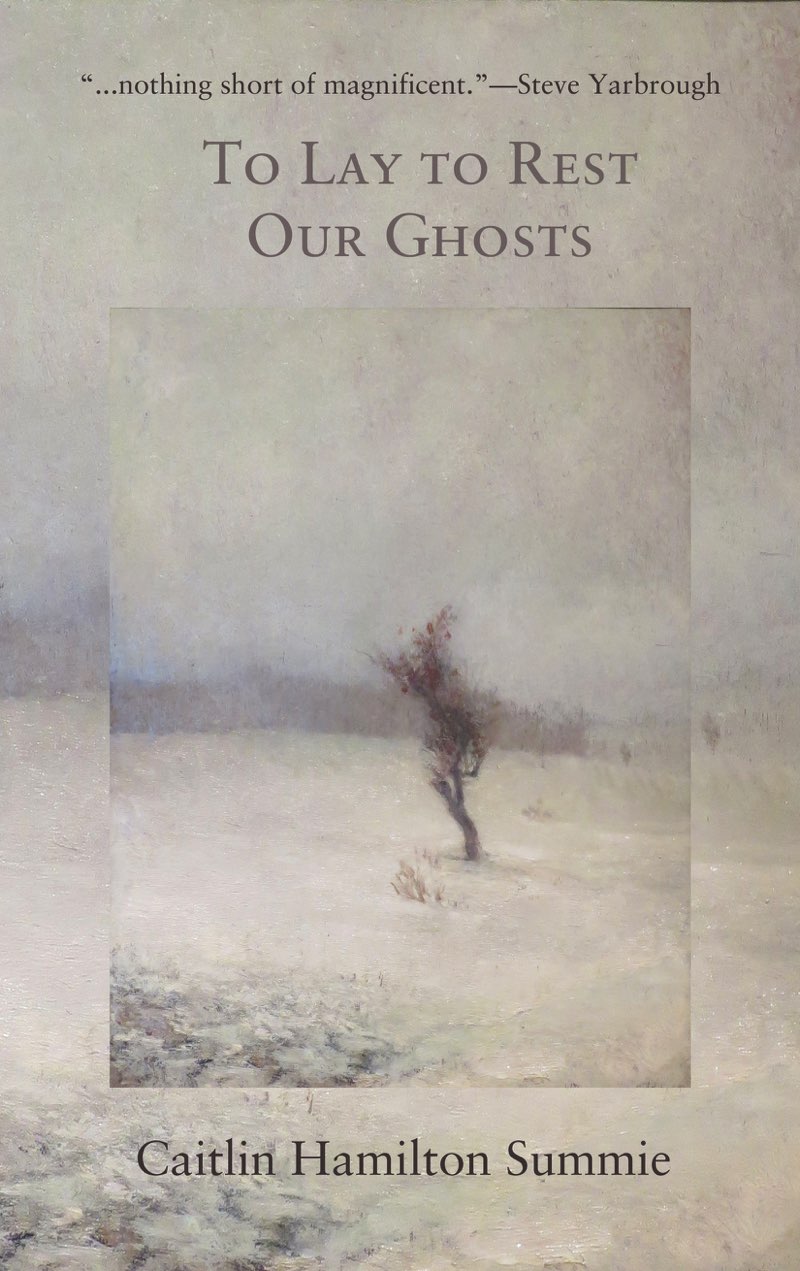

Praise for To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts

" W hat is remembered ; what is missed; what will never be again... all these are addressed with the tenderness of a wise observer whose heart is large enough, kind enough, to embrace them all without judgment.... intense and finely crafted.... her stories reach into the hidden places of the heart and break them open to healing light, offering a touch of grace and hope of reconciliation."

Foreword Reviews, starred review

I ts been a long time since I read a collection of stories that amazed me from cover to cover, but thats what Caitlin Summies To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts did. With the grace and elegance of a master, Summie lays bare our vulnerabilities and desires and hopes in equal measure. The result is one stunning story after another, each as lovely and heartfelt as the one before. If youre a fan of Grace Paley or Ann Beattie or Tobias Wolfe, youll surely find something to love in these pages.

Peter Geye, author of Wintering

T here are lots of story collections with a very strong connection to place. There are also lots of collections with great range in their locales.To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts is a wonderful achievement because it meets both of those goals. I found myself attached to each story and its placescarefully enhanced by characters whose lives and thoughts and situations are quite easy to feel connected to.

Hans Weyandt, Milkweed Editions Bookstore

C aitlin Hamilton Summie is an author in full flower. These ten stories embody craft, care, an obvious love of language, and a deeply generous understanding of people and places. To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts is a completely pleasurable read.

Joni Rodgers, NYT bestselling author of Sugarland

T o Lay to Rest Our Ghosts is nothing short of magnificent. The authors sense of place is extraordinary, and it informs every word she writes. Her characters are as real as anybody you know in the town where you live, and their lives are depicted with quiet dignity. The stories are both intense and economical. Ive gotten very hard to please, but I loved this book.

Steve Yarbrough

J immy Weston had his Dads dog tags. He wore them around his neck on a steel chain and had this funny habit of rubbing them back and forth between his fingers. Wed be playing marbles or collecting tin for the war effort; wed be jumping on cracks to break Hitlers back or be waiting, just waiting, for the whole thing to end, and Jimmy would talk and rub those dog tags together, and Id listen. Thats mostly how I remember those days: Jimmy and me sitting on the curb, tired of marbles, tired of tin, him with that sound of his father, and me with nothing of mine but his name.

My father enlisted when I was four. He was quiet about it, according to my mother, but she knew he was planning on signing up. Before the war, the men met after their day shifts for a beer or a game of ball or cards, but not after the war began. Then they started home when the whistle blew. Too sick of the brewery to think of beer, too distracted to finish a game, they peeled off from one another at each doorway with cat calls and jokes and day weary voices. But then the talk began.

T he sky would go pitch , lights would fill window frames, and then the men would come over. Jimmys Dad and my uncles and others my mother does not name. Shed be standing at the sink, hands greasy and dripping and slick, and there would be a soft rap on the door, or the low groan of the wooden porch steps, or just the feeling, suddenly, that she was not alone, and shed turn, and there was Uncle Joey, or Uncle Ray, or any of them.

How many? I once asked. I was fifteen, maybe sixteen, wanting to hear the details again, confident in my newly discovered remove.

She shrugged. Five, she said, six, sometimes seven. All around that little kitchen table.

How come they came to our house?

She shook her head. We were the mid-point, half way down the block. I dont know. Maybe I served the best coffee. She smiled, but her smile quickly faded.

They knew, my mother said, that they wouldnt all come back. We all knew that.

I nodded, but only as a reflex because we did not all know that. I didnt. Jimmy didnt. We were the littlest ones, the ones who learned slowly, much later than everyone else, what the absences meant. I remember catching on. I remember sitting on the curb late one afternoon in the middle of winter, wrapped in wool, listening to Jimmy rub those dog tags together. I remember thinking, as the sun went down and the chill set into me, that Jimmys father was up there somewhere, in bits and pieces.

J immy Weston and I got to be friends playing marbles. I was sitting on the sidewalk outside the house one day, placing my marbles along the cracks in the pavement in neat rows of blue and yellow and green. My favorite marble was a solid red, the only red one I had, and it was my shooter. The day was quiet, a Saturday, or maybe even a Sunday, and cool. I wore a plaid hand-me-down jacket from my cousin, Linda, and my cousin Larrys old baseball cap. I was the youngest and got whatever old clothes fit.

I didnt like Jimmy much. Jimmy had pale skin and freckles and a soft voice that was sometimes hard to hear. We were the same age, younger than most kids in the neighborhood, but we didnt spend much time together then. Every time I asked him to play, he had a cold or the flu or a sore tooth or his left toe was throbbing. I stopped asking. I played by myself or with two boys down the street, Tommy Ocerly and John Swenson, but Tommy and John were best friends, and I was an awkward addition.

That day I sat on the curb and admired my marbles. I had twenty-one in swirling colors, and I loved to watch the colors as the marbles shot across the pavement. I was used to being alone, and Id started talking to myself, using a voice like the ones I heard on the radio, talking in the same clipped manner. I started to describe my marbles, imagining the marble tournament of the world, imagining a final match between me and a nip maybe.

You talking to yourself, Dolores?

I looked up quickly, and coming across the street with a small cloth bag gripped in one hand was Jimmy Weston, limping. I shook my head at his limp, but he misunderstood.

Then you must be talking to me, he said, and stepping in a hop over the curb and up onto the sidewalk, he knelt down. He let his marbles out onto the pavement slowly, holding them in with his hand and forearm. He looked me in the eye. Ill play you for the red one, he said.

A ll the men in my family went, first Dad in 42, then Uncle Ray, then Uncle Joey, and so on, until all five were away in Europe. They disappeared quickly, I guess, though one by one, and then the women pulled together. This is what they tell me, my mother and my aunts and my cousins: Grammy picked up the phone after the last man had gone and called my mother; and my mother called her sister, and that was that. Five women and their children moved into Grammys once spacious and echo-y house in Kansas City, and waited for their men to come home. For my mother and me, the move was minor, only one block down.

I knew the men in my family by photograph, but the only photograph I studied was my fathers. Id sneak into the room my mother shared with my aunt, and Id stare at the photograph of my Dad on her dresser. Id look at the ridge in his nose, the little bump part way down, and Id rub my nose, which was smooth and long. Yet the minute I closed my eyes and tried to remember his face, I saw nothing. On a good day, I remembered the smell of soap when he hugged me, the smell of cigarettes in his clothes and hair. On a good day, I remembered his voice saying my name.