FOREWORD

HARRIS DIAMANT

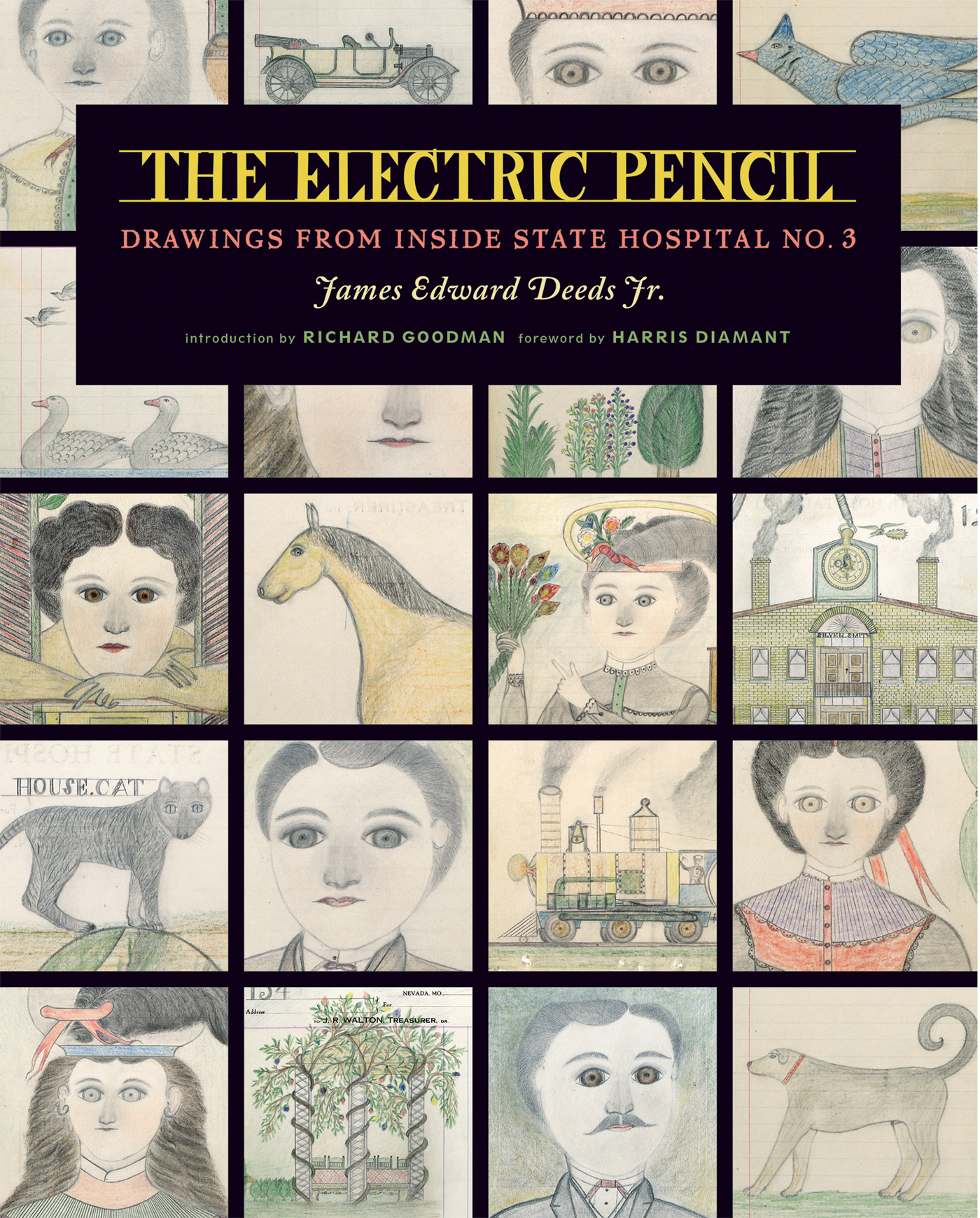

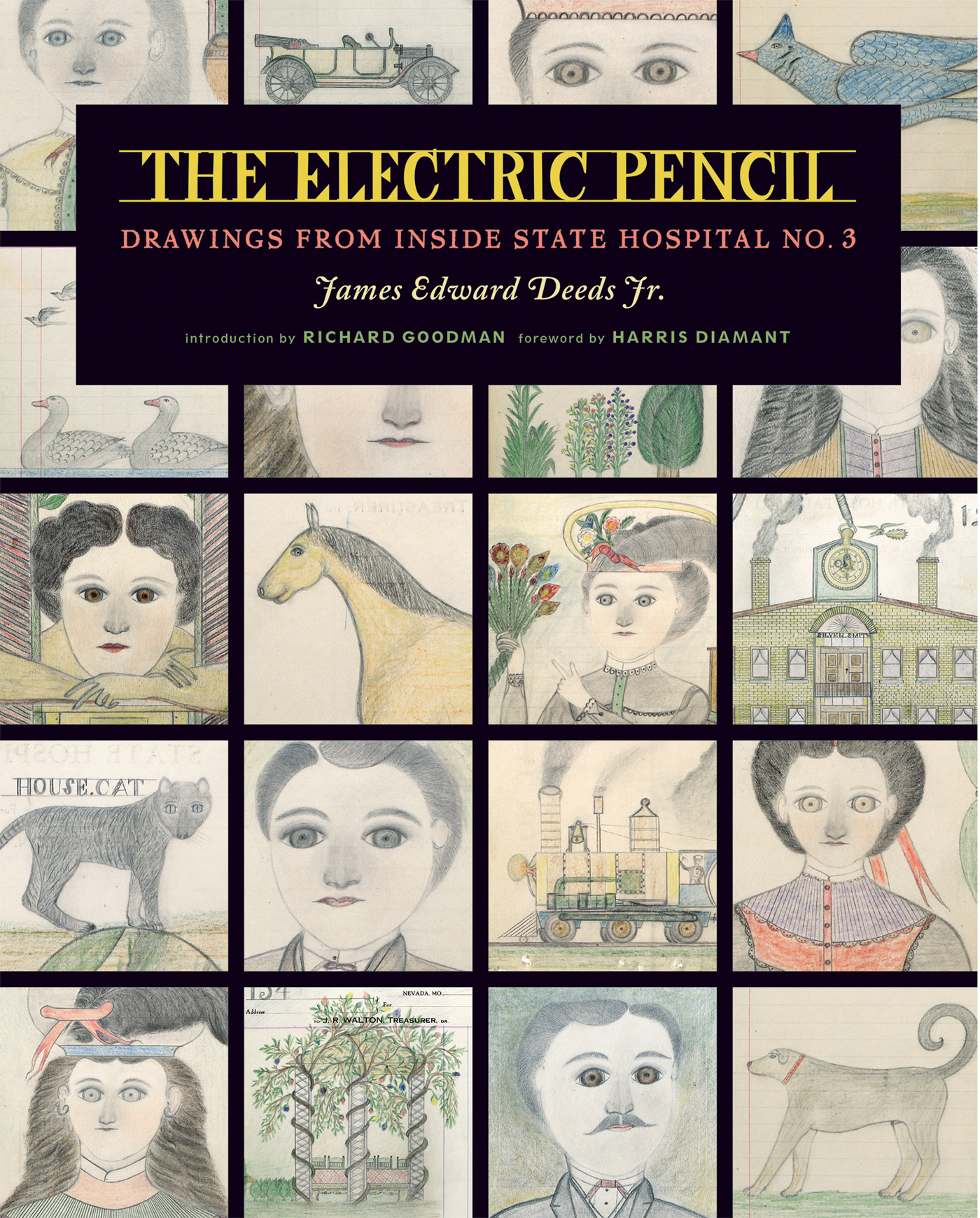

One day in 2006, trolling through eBay (as Im wont to do), I made a fortuitous discovery. A handful of intriguing drawings appeared, and then, in front of my eyes, the listing was swiftly pulled. I embarked on a quest to track them down. The search eventually brought me to a once-in-a-lifetime treasure: an album of 283 masterful drawings in a handmade album. Each drawing had been executed on a ledger sheet with the imprimatur of State Lunatic Asylum, No. 3 or State Hospital No. 3, in Nevada, Missouri.

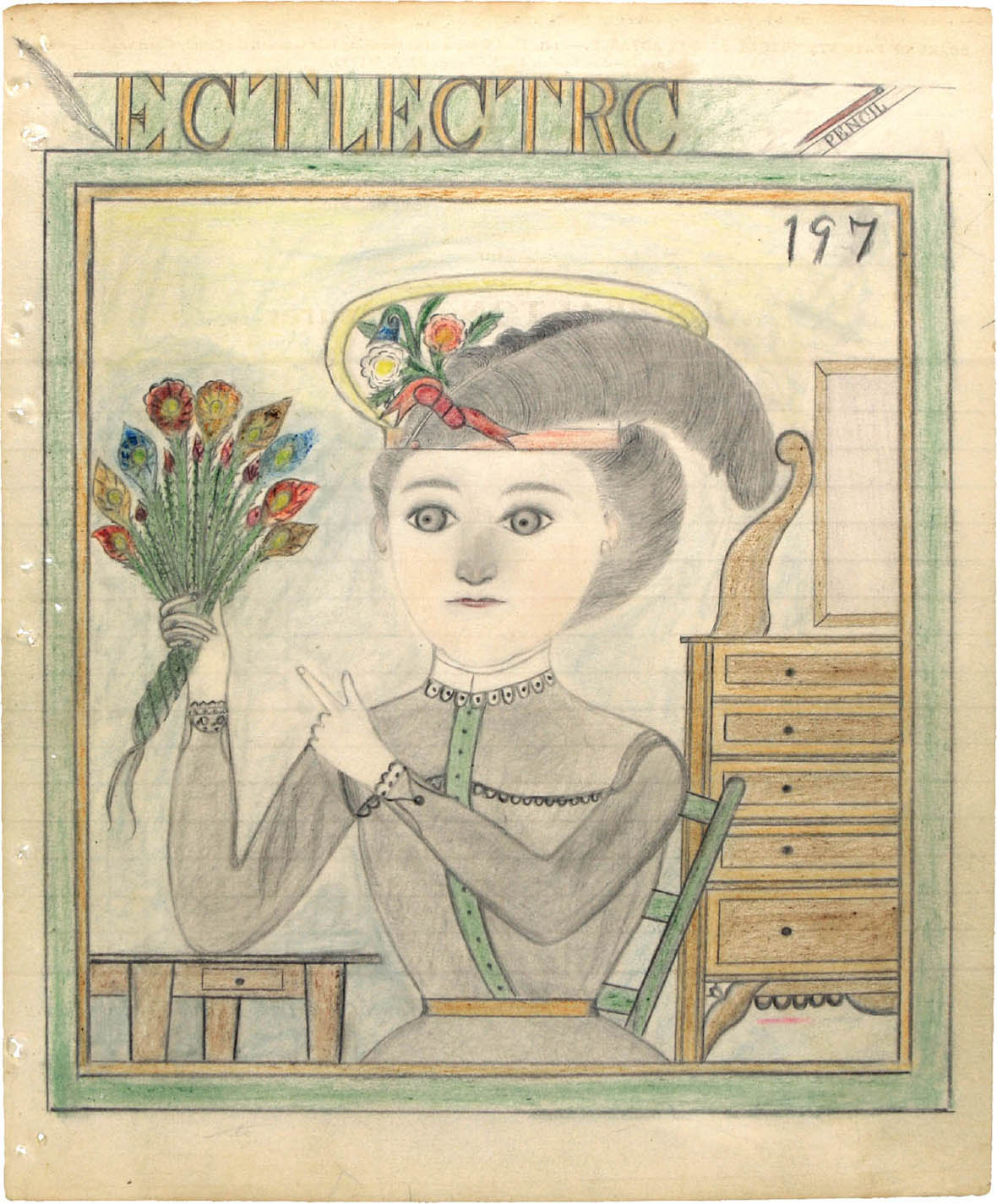

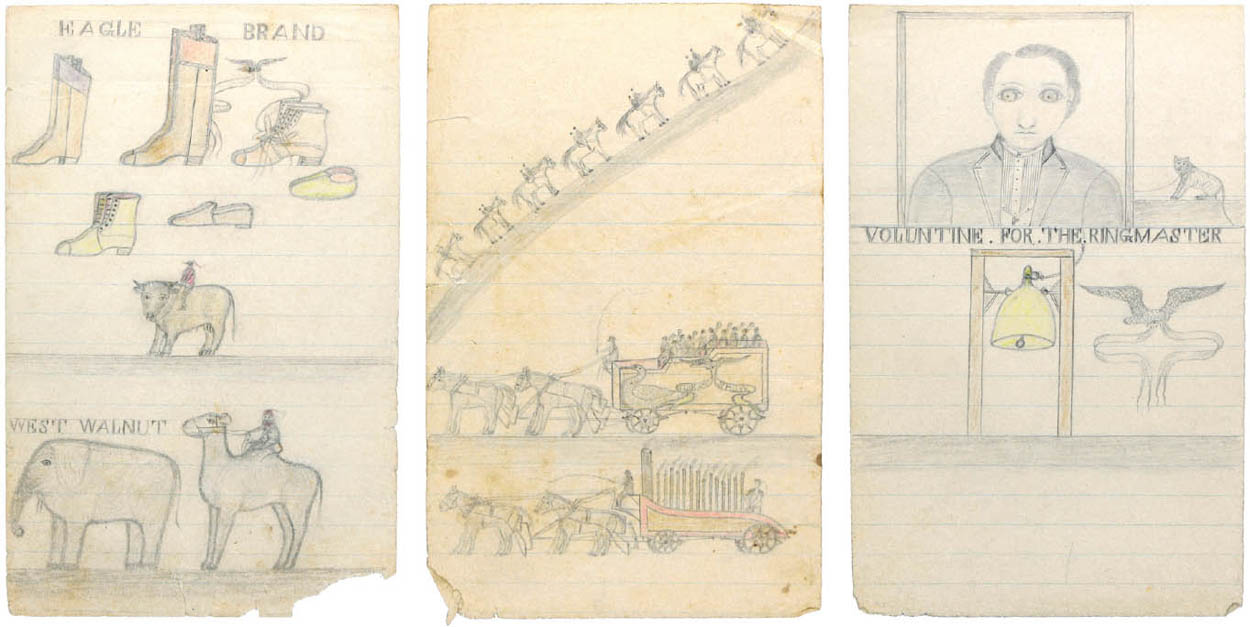

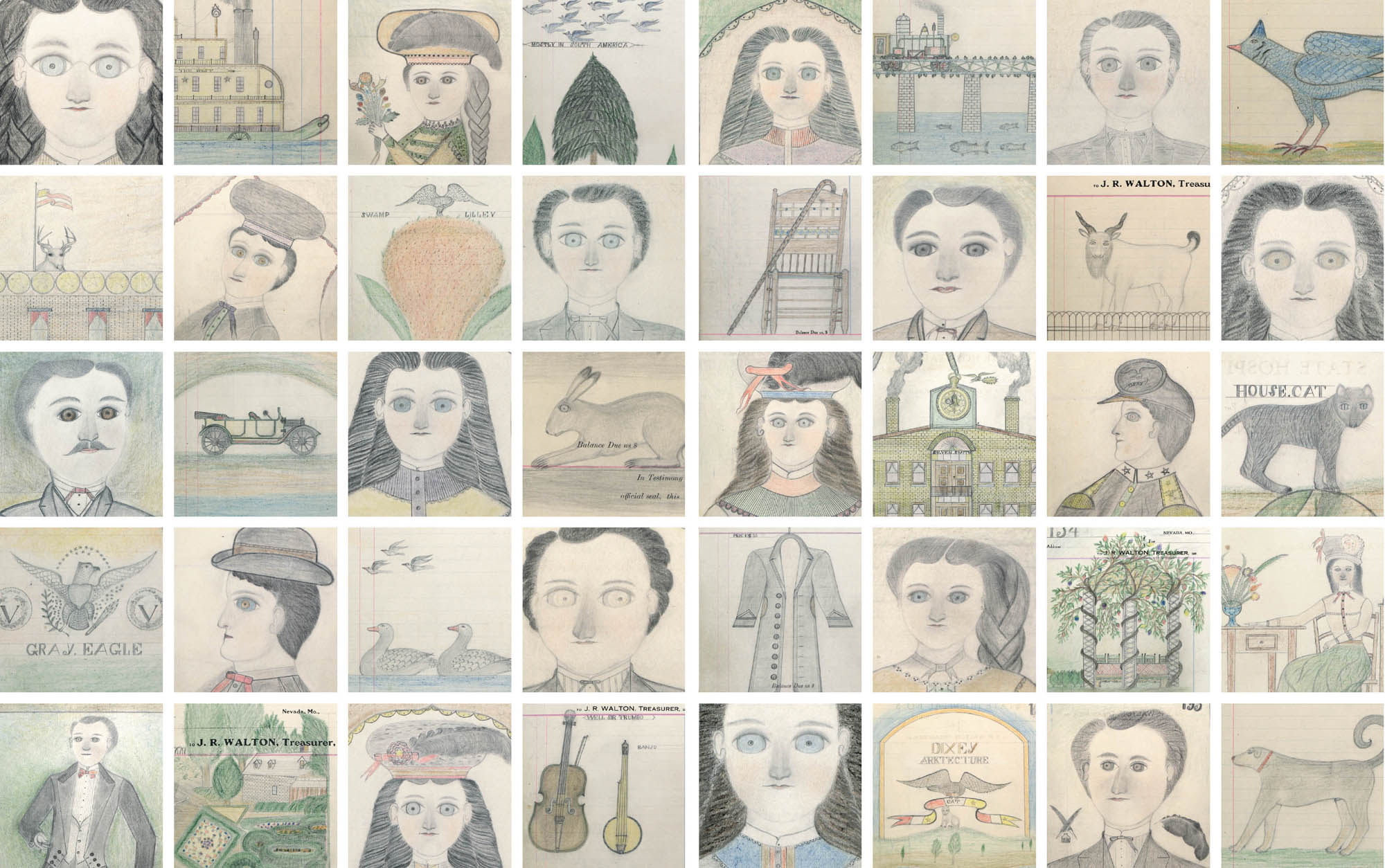

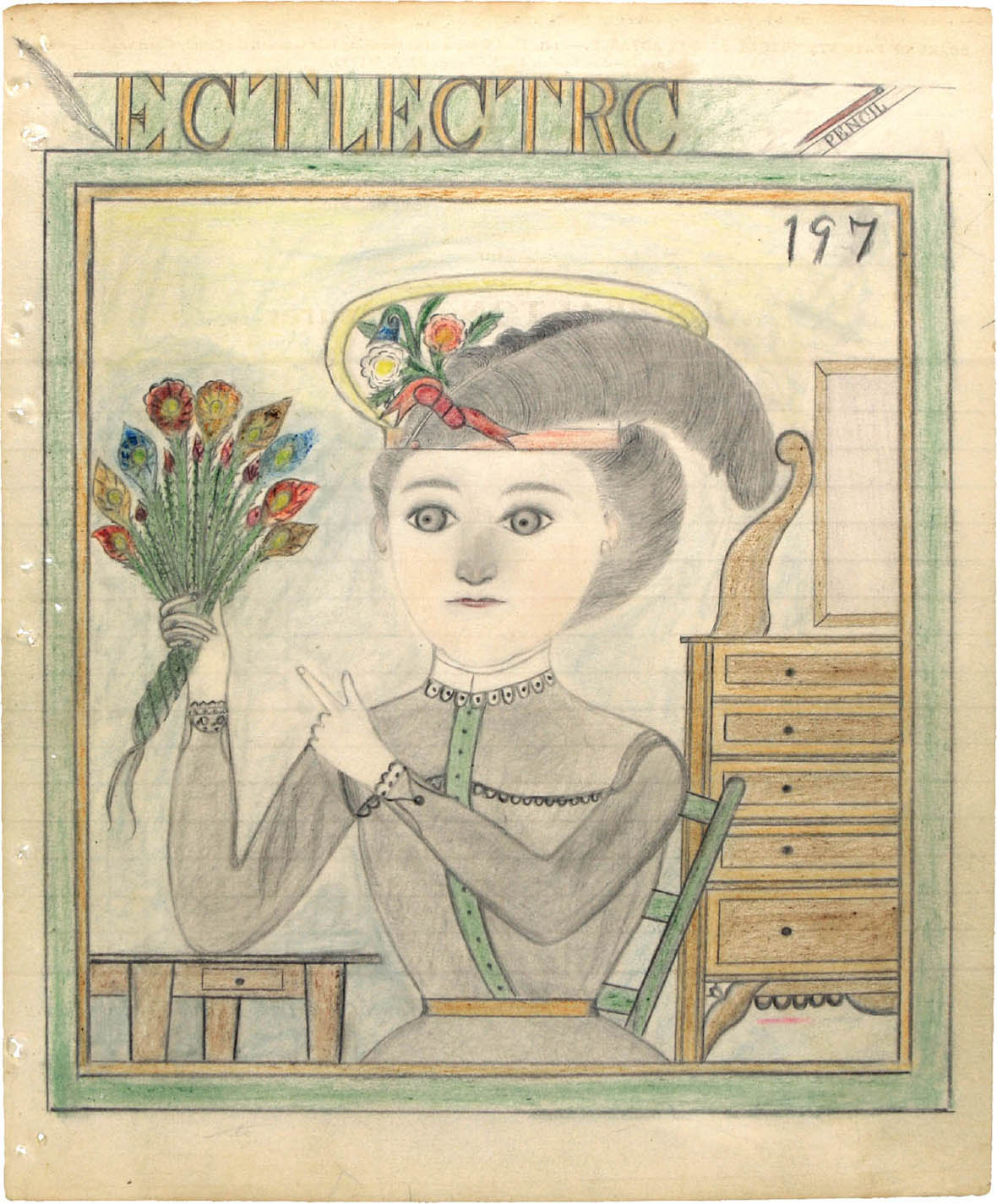

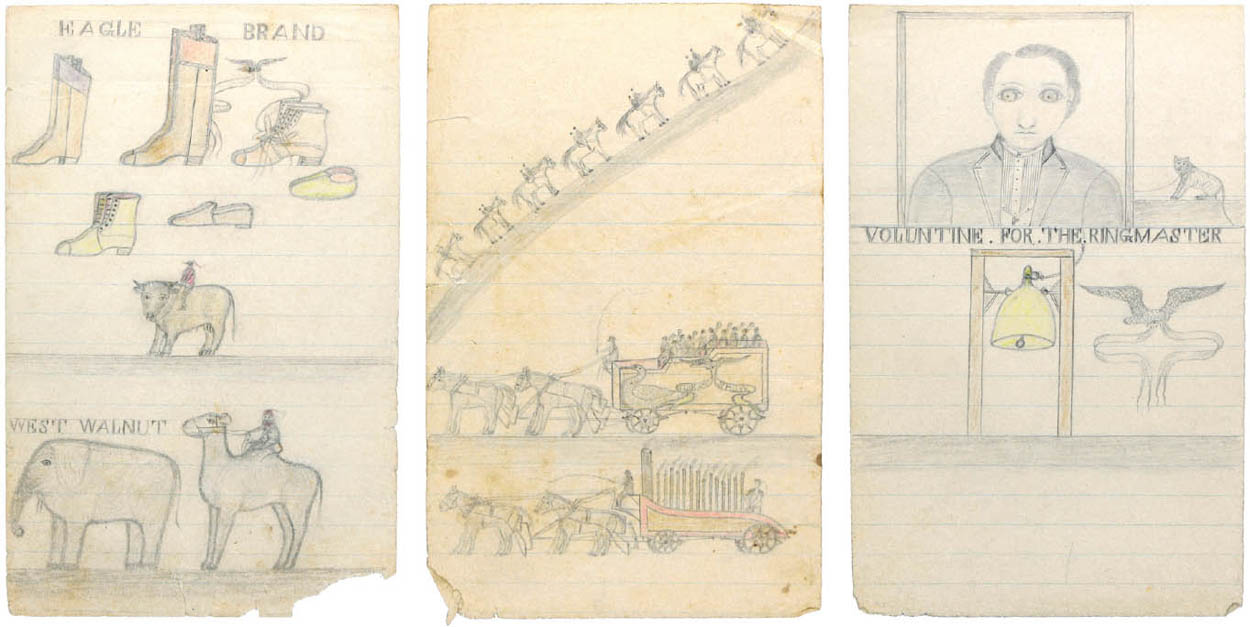

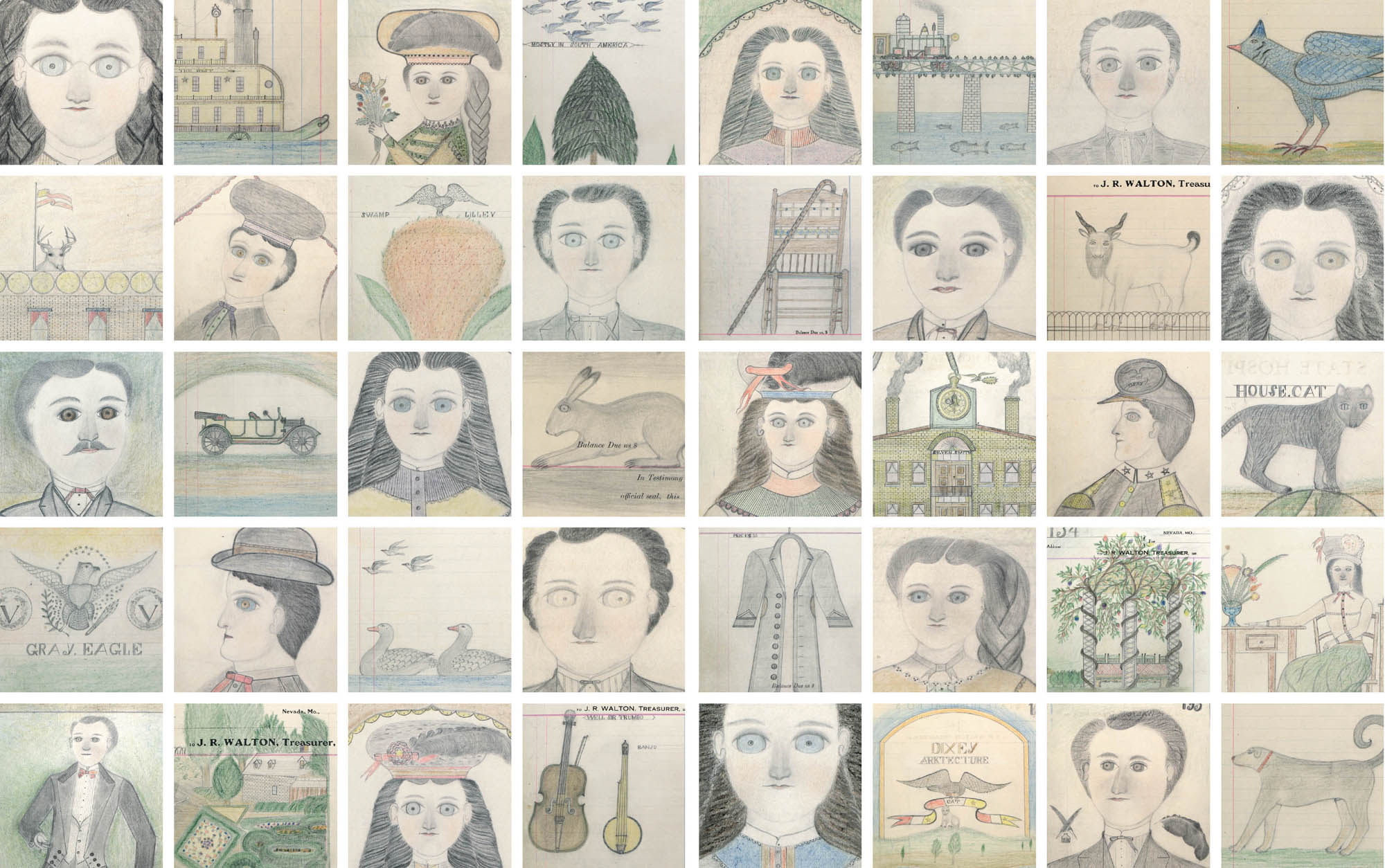

The artwork is a treasure trove of cluesa diary that tells a story in the artists own personal symbolic language. The album and drawings look like artifacts from a distant time: arresting portraits of people with gaping eyes wearing nineteenth-century clothing, Civil War soldiers, antique cars, fantastic boats and trains, country landscapes with roaming animals, and other drawings that seem fanciful and bizarre. The oxidized edges of the old paper make the drawings look like treasure maps. The artist had hand made and hand bound this album of drawings with loving care.

Where the drawings were made was instantly apparent, but nothing else beside its beauty and uniqueness was known about this artwork. Researching the clues in the drawings brought up many other questions: Who was the artist? Was the artist a he or a she? When were the drawings created? What was the connection with State Lunatic Asylum No. 3?

Three additional single-sided loose drawings were included in the album.

As an artist, I was intrigued by the skillful, one could say obsessively, detailed draftsmanship of the work, each brick rendered with precision. The portraits are arresting, and despite the haunting faces, this is a peaceable world with no aggressive violence. The artist lovingly captured his subjects with a subtle use of color and shading, using the side of his pencil to create the smutty noses that enhance the modeling of the faces. The clothing and intimate objects of daily life are presented with solemnity and respect.

As a folk art and outsider art dealer and collector, I was thrilled by the discovery. I knew this was a singular workrare and remarkable.

I began an adventurous search for the artists identity, which led me to the Deeds family and the touching, disturbing life story of Edward Deeds, institutionalized for most of his adult life.

Amazingly, the album had been lost in 1970 and miraculously rescued by a fourteen-year-old boy, who kept it safe for thirty-six years until improbably, it came to light a second time, intact. I was able to acquire the collection, preserve and document the drawings, and embark on this journey of discovery. It is a gift and a miracle these drawings were saved.

Edwards story speaks to the human need to communicateand the artists need to make work in spite of horrendous circumstances. Looking at the well-worn covers, I envision Edward clutching the album like a talisman. I imagine the drawings were a source of comfort for hima formal, gentle world he created as a sanctuary, a world in contrast to the harsh reality of his long life of abuse, hospitalization, and the frightening treatments he suffered at State Hospital Number 3. I am thrilled that Edward Deedss wondrous art has found its own life on the world stage, telling a fanciful tale beyond the walls of the hospital and the tragic artist who was its creator.

INTRODUCTION

THE IMAGINED NOSTALGIA OF JAMES EDWARD DEEDS JR.

RICHARD GOODMAN

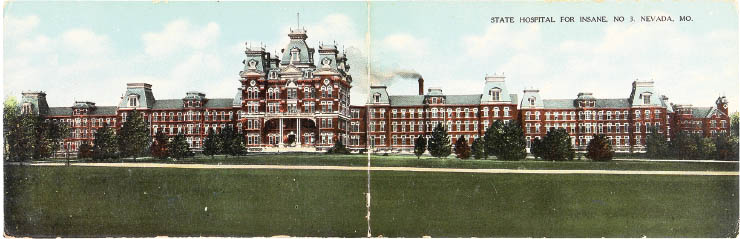

On June 7, 1936, a slender twenty-eight-year-old man with a ninth-grade education entered a massive, eight-wing brick structure in Nevada, Missouri. In its design and scale, this building would have fit in perfectly well in nineteenth-century London. It was as if the Victoria and Albert Museum had been set down on the outskirts of this small town in western Missouri. [] Except that it wasnt a museum. It was a hospital for the mentally ill. The mans name was James Edward Deeds Jr. He was admitted to State Hospital Number 3 in Nevada with a diagnosis of dementia praecox. He was one of about seventeen hundred patients who lived in that building, some for a few months, some for years, some until they died. James Edward Deeds Jr., called Edward by his family, would reside at State Hospital Number 3 for the next thirty-seven years. He would begin his residency during the height of the Great Depression and continue it through the first moon landing. He would know no other life than inside the walls of institutions. He would never marry, never father children, never own a house or a car, never travel, never walk through the world freely.

Postcard, ca. 1920, of the entrance gate to State Hospital Number 3, in rural Nevada, Missouri, featuring the giant eagle sculpture depicted in Edward Deedss drawings.

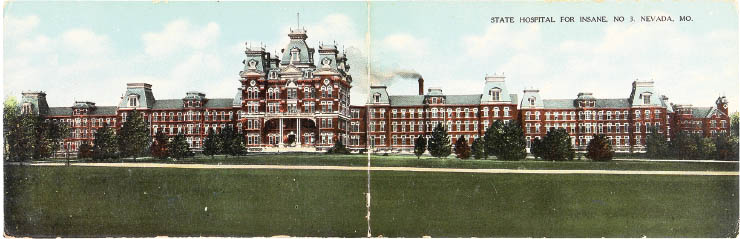

Double postcard of the massive State Hospital Number 3. It was the largest building west of the Mississippi when it opened in 1887.

Postcard of the reception hall of State Hospital Number 3. The goal of the asylum was to create a home and a haven for people suffering from mental illness.

Yet, Deeds created an entire mysterious, enduring world with pen, pencil, crayons, and the discarded pages of a hospital ledgerand with his own unconfined imagination.

Edward Deeds and his art would have disappeared from historyand, in fact, until just recently, didif it hadnt been for the scavenging eye of a fourteen-year-old boy. Walking down a street in a residential section of Springfield, Missouri, one day in 1970, the boy spotted something in a trash heap. It was a worn, dull portfolio made of leather and cardboard. Its green and grayish cover had a patina of age and use. The boy pulled it from the trash. In it was something that must have astonished and befuddled him: 283 drawings that had been stitched crudely but resolutely into the book, along with three loose drawings. He would have immediately seen that the drawings were made on ledger paper labeled State Hospital No. 3. There was no indication of who had made these drawings; there was no name on the book. They were strange yet purposeful, drawn with a fastidious delicacy. The boy had certainly never seen anything like them. No one had.

What did he make of the many drawings of large-eyed men and women staring straight at him as if they were transfixed, yet somehow not threatening? They were dressed in clothes he might have seen in black-and-white nineteenth-century formal photographs. What did he think of the drawings of animals, some drawn accurately, some awkwardly? Some were familiardogs, cats, ducks, and squirrels. Some he had only seen in books or in the zoo or at the circustigers, lions, elephants, and camels. He saw drawings of steamboats, smoke billowing out of smokestacks, and of old cars he might have seen in silent films on TV. He saw clocks and fans, factory-like buildings and landscapes dotted with slim, tall trees. There was a baseball team in old-fashioned uniforms that might have especially caught his eye. There was a Wild West show.

Next page