This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

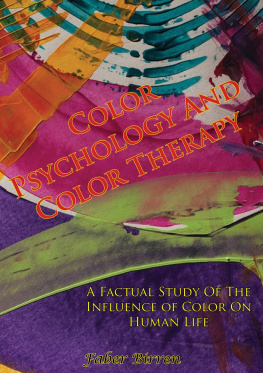

COLOR PSYCHOLOGY AND COLOR THERAPY:

A FACTUAL STUDY OF THE INFLUENCE OF COLOR ON HUMAN LIFE

BY

FABER BIRREN

Typography and Illustrations by Raymond Lufkin

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

To DEANE B. JUDD

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

When COLOR PSYCHOLOGY AND COLOR THERAPY first appeared in 1950, it was fairly well reviewed in the medical press. There were reservations, of course, especially where I launched into mysticism, but for the most part the medical reviewers found the text not without a measure of interest.

What is now saving the day for color therapy is the rising science of psychosomatic medicine, which admits that man has a psyche that cannot be divorced from his body. The fears and tensions that cause the ulcer (or the asthma or the allergy) must be relieved or the person never will be well. The value of color therapy in psychosomatic disease cannot be denied. However, as this book strives to show, the influence of color is by no means limited to the psychological realm; its direct biological and physiological effects are rapidly becoming more evident as new research data accumulate.

In the years since the publication of the first edition of this book, I have continued my own studies and engaged in correspondence with other workers all over the world. A review of some of the more important research results from 1950 to the present is included in a new section of the present edition, Part 5, New Biological and Psychological Findings. Thus brought up to date, it is my hope that this volume will be accepted as a standard reference work in the field of color psychology.

FABER BIRREN

New York

1961

INTRODUCTION TO THE REVISED EDITION

Faber Birren is not a theorist but a very practical craftsman. Whether he is reading the works of mystics, or of biologists, or of psychologists, he is reading and studying them not for their theoretical structures, and one might say not even to know whether what theyre saying is true but, quite simply, in order to find something to use in picking the colors for a mental hospital or a battleship, or a missile base, or to make new kinds of colored paper to print on, or to make a new home attractive, or to make new kinds of colored bricks for buildings.

Most of us bring our preconceptions and prejudices wherever we go. We are like horses with blinders on, going only in the direction we have been set to go. What is so extraordinary and so fruitful about Faber Birrens practicality is that it goes everywhere quite utterly without prejudice. Unlike most of us, Faber Birren, now just as when he was a young man, is willing to learn from anybody. He has learned from the most diverse people, from people who contradict each other, from people who denounce each other, from the occultists and mystics as well as from the biologists and agnostic scientists. He dares to learn from the occultists and mystics as well as the scientists.

It is necessary to emphasize this because otherwise Part One of this book, THE HISTORICAL ASPECTS, may appear to the reader to be a speedy commentary on a dead past, to be read as mere background after which one can turn to the rest of the book for some really scientific knowledge. Faber Birren does speak of superstitions, cults, and similar invidious terms, as if to show that he is not being taken in. But these terms should not obscure the full extent of his acknowledged debt to the mystic arts. Unfortunately, too, the first section of his book is much too short for what it contains andto take but one examplethe reader will hardly grasp from the one quotation from E. A. W. Budges great work on amulets how much one can learn from this book. One of the fullest sections in this first part is on the work of Edwin D. Babbitt, but the reader will find it difficult to be sure what Birren has accepted, and what not. (It is pleasant to report that Birren has promised an abridged edition of Babbitts THE PRINCIPLES OF LIGHT AND COLOR.) The reader whose appetite has been whetted should understand that he will do best if he takes this first part of Faber Birrens book as a guide to the literature which is mentioned rather than a substitute for it.

Birren entered the University of Chicago in 1920, majoring in education. Soon he decided to make color his lifework. There was no institution which gave instruction in this subject. He left the university after two years and set up his own system of study. He read all the books on light and color he could obtain from the Chicago Public Library and the Library of the American Medical Association, and entered into correspondence with various European psychologists, physicists, and ophthalmologists. He also made color experiments of his own.

To test the truth of the old quotation, paint the dungeon red and drive the prisoner mad, he painted the walls, floor and ceiling of his room vermilion, curtained the windows with red glassine, and installed red light bulbs. He spent weeks in this room and found the red surroundings only made him feel quite comfortable and cheerful.

To support himself during these early years of research, Birren worked for a publishing firm and occasionally wrote articles on color for medical and technical journals. In 1934 he rented an office in Chicago and set up as a color consultant. But it was not until he solved a problem for the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, that manufacturers took an interest in his work.

The public was not buying billiard tables for basement rumpus rooms. Birren found it was largely a matter of color psychology. American women would not have the green-topped billiard tables in their homes, he had learned, because they associated this color with cheap pool halls and gambling dens. Birren recommended changing the color of the table covering to a soft purplish tone. The company complied and home sales of the purple-topped tables climbed quickly.

By 1935 Birren was called to New York City so frequently that he decided to move his offices there.

In the Southern textile mills of Marshall Field & Company, Birren reduced fatigue by giving workers light green end-walls He relieved monotony for thousands of telephone girls by introducing yellow into the decoration of exchanges. He reduced accidents in the Caterpillar Tractor Company by devising a new color scheme for its 72-acre plant. The advent of fluorescent lights brought Birren many new accounts, because special color treatment was needed to spare employees eyestrain and keep objects from looking ghastly.

Next page