ALSO BY ANTHONY ARTHUR

Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair

For Duncan,

who likes adventure stories,

and, as always and forever,

for Carolyn

Tho much is taken, much abides; and tho

We are not now that strength which in old days

Movd earth and heaven, that which we are, we are:

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Ulysses BY A LFRED T ENNYSON , 1842

CONTENTS

PART ONE

ONE :

TWO :

THREE :

PART TWO

FOUR :

FIVE :

SIX :

SEVEN :

EIGHT :

NINE :

TEN :

ELEVEN :

PART THREE

TWELVE :

THIRTEEN :

PROLOGUE

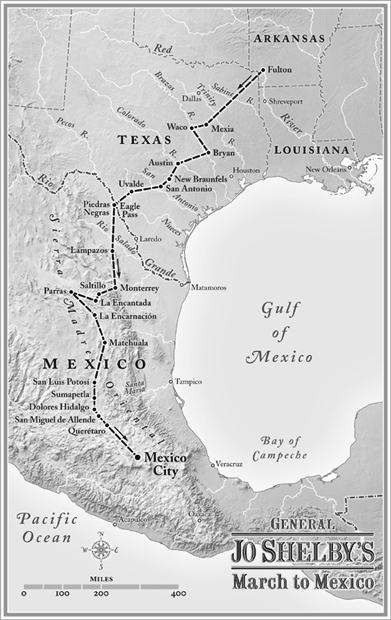

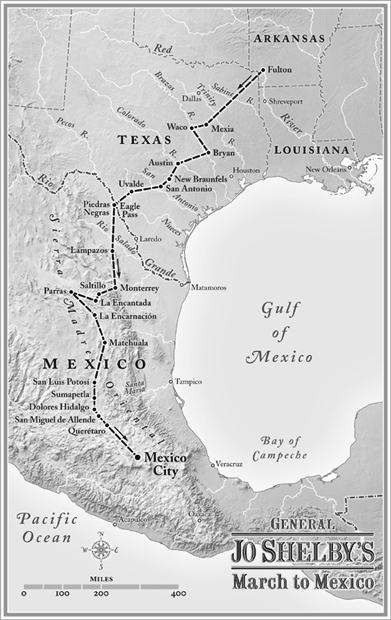

The Burial of the Flag: Eagle Pass, Texas, July 1, 1865

F ive men stood knee-deep in the muddy shallows of the Rio Grande, each clutching an edge of a tattered Confederate flag that billowed lightly in the soft early morning breeze. On the other side of the wide river, still rushing from the late spring rains, were the low adobe huts of Piedras Negras and two thousand troops loyal to their beleaguered and exiled president, Benito Jurez. Beyond lay the turbulent nation of Mexicovast, hostile, alienuneasily ruled by the French army supporting the Hapsburg interloper known as the emperor Maximilian.

Above the men, on a bluff overlooking the river, lay the dusty border town of Eagle Pass, Texas. This desolate crossroads had been the last outpost of the shattered Confederacy. Behind it loomed the newly triumphant United States, now nearly as foreign as Mexicoand, to their minds, no less hostileto these men who had tried for so many long years to dismember it.

Gaunt, bearded, clad in threadbare gray tunics, the five soldiers looked years older than their ageyet only one was over forty. Their names were Slayback, Elliott, Williams, Gordon, and Blackwell, and they were colonels in General Jo Shelbys Iron Brigade of Missouri Volunteers. That is, they had been. Now the war was lost and the brigade disbanded. Most of its thousand-plus survivors had gone back to their farms and villages, and to their families. Fewer than two hundred of the Missourians remained, along with a motley crew of adventurers, fortune hunters, and deserters from half a dozen armies who had stuck to Shelby like cockleburs on his march through Texas.

Shelbys colonels and his men knew why they stayed with him, and it was more than mere self-interest. He was the Jeb Stuart of the Trans-Mississippi West, as the newspapers had itthe daring cavalry commander renowned for his slashing forays behind Union lines in Missouri and Arkansas, and tarred by some as a bushwhacker who harbored the infamous William Quantrill and the James brothers. Shelbys brigade had followed him on his famous raid into Missouri in 1863six weeks of attack and parry, of plundering Union storage depots and capturing Union soldiers, of sleeping in saddles. And they had been with him in 1864 when he rescued the Confederate forces under the lumbering general Sterling Price from certain destruction at the critical Battle of Westport, near Kansas City. Jo Shelby had risked their lives many times for the Confederacy, which was no more. Now they would place an all-or-nothing bet on his latest gamble, this grand final adventure, the march into Mexico.

Some of those watching the flag ceremony from the bluff above the river were not Shelbys soldiers but prominent men, years andin some casesdecades older than the young general. They had been senators, congressmen, and governors, and there was a clutch of high-ranking officers, including Major General John Magruder, hero of the Battle of Galveston. Like Shelby, whose home and businesses in western Missouri had long since been reduced to smoldering ruins, these men had nothing to go back to. When Shelby had vowed to seek a new life in Mexico, they willingly acknowledged him as their leader.

Shelby sat silently on a sorrel mare near his officers in the river, leaning forward slightly, resting his crippled right arm on the pommel of his saddle. In his left hand he held his slouch hat with its famous curling black ostrich plume. His face was deeply tanned under a thatch of black hair, his expression remote and stern under a heavy russet beard. Not a large man, bow-legged from years in the saddle, lean but broad-shouldered, he conveyed motion and force even in repose. And violence: He fought like a man who invented fighting, wrote an admiring biographer, and the men of the Missouri Cavalry Brigade looked on him as the perfect commanding officer: colorful and dashing, reckless with his own life but careful with those of his men.

Abruptly Shelby spoke, halting the officers as they prepared to fold and sink the flag. They waited as he dismounted and waded slowly toward them. He withdrew the black plume from his hat brim and laid it gently within the folds of the flag before it vanished beneath the muddy water. This battle, his typically picturesque gesture saidthis four-year battle that the North called the Civil War and the South the War of the Rebellionwas over.

Another struggle beyond the Rio Grande awaited. For Shelby and his men, as Tennyson said of Homers Ulysses, it was not too late to seek a newer world. None of them could know whether that world would be better or worse than the one they were rejecting.

PART ONE

THE CALL TO ARMS

183065

ONE

From Privileged Youth to Border Ruffian

I n the early 1850s, a dozen years before he crossed into Mexico, nothing could have compelled Jo Shelby to leave the world of privilege and wealth into which he had been born. Well before his birth, the Shelby name was a famous one in Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, denoting a numerous, widespread, and very successful clan. A common ancestor from Wales, Evan Shelby, had arrived in Pennsylvania in 1735 with his wife and four sons. Evan set the tone for the strain of violence and eccentric independence that would emerge in some of his progeny: Presiding at a wedding in Maryland, he blessed the couple by saying Jump Dog, Leap Bitch, and Ill be damned if all the Men on Earth can unmarry you. He also threatened to job a fork into the Gutts of the groom when he showed signs of backing out.

Evans energetic sons soon moved west and south, becoming wealthy entrepreneurs and men of property along the Appalachian frontier. His second son, David, sowed crops and begat children, eleven in all; the ninth of these was Orville, Jos father, born in 1803.