Table of Contents

To my friend Jo

Murdered in 1941

And to all the victims

Of the Nazi barbarity

For one pleasure a thousand pains

Franois Villon, 1463

Foreword

by Gregory Woods

On Remembrance Sunday in November 1977, I took part in a small ceremony to lay a pink-triangle wreath on the war memorial in Norwich, England. I was a doctoral student at the University of East Anglia on the edge of the city, writing my thesis on gay literature. We members of the student gay group had persuaded the students union to pay for and lay the wreath, in memory of the many men killed by the Nazis for being homosexual.

The announcement of our plans had caused controversy in the local pressostensibly because the nations war memorials and the traditions of Remembrance Sunday (on which the United Kingdom formally celebrates the anniversary of Armistice Day, 1918, which brought the First World War to an end) were intended to commemorate British victims of recent wars, not German and other European non-combatants. But there was, we judged, also a homophobic edge in the response to the announcement of our plans. The British Legion, which presides over the formal events of national commemoration, would not allow us to take part in the morning wreath-layings and two-minute silence; so we would lay our pink triangle in the quiet of the afternoon.

Later that day, we were confronted by a small group of hostile protesters. There was no overtly physical threat, but a lot of shouting and finger-pointing. They accused us of being unpatriotic. We accused them of being homophobicbut this word was newly coined, and they had no idea what we meant.

When the president of the students union went to lay our wreath, a protester snatched it from his hands and tried to hurl it down into the marketplace below the memorial, but it hit the railings and fell to the ground. The angry group shouted at us for several minutes and then abruptly left the scene. We handed the slightly battered wreath to the president, and he placed it on the memorial.

Some time later, two uniformed members of the British Legion removed the wreath and carried it off to their car. We intercepted them and, after a long but quite goodnatured argument, they handed it back to us. Once again, we put it back on the memorial. But by the evening it had vanished.

There was nothing especially imaginative, innovative, or daring about the political gesture we had taken part in. Since we were not an especially radical group, we were simply copying what we had heard that other groups had done at any of the universities in Londonperhaps where gay liberationists could guarantee themselves a decent crowd when organizing such demonstrations. The so-called gay holocaust was one of the themes of the time, as academic historians were piecing together and making sense of the facts of the matter. As an event or series of events, it stood for the extremes to which the oppression of homosexuals might be taken. It merited George Weinbergs newly minted term homophobia. The gay liberation movement had adopted the pink triangleas forced on many homosexual internees in the Nazi concentration campsas one of its symbols. We wore it on lapel badges; it often graced the mastheads of our newspapers; we carried it on banners during our demonstrations.

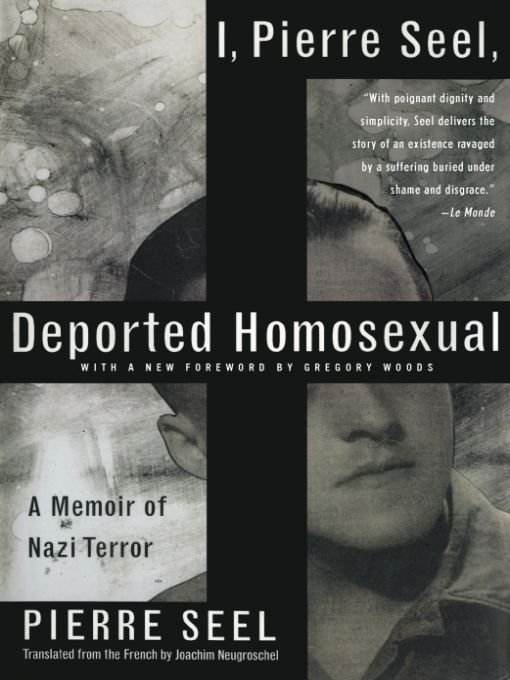

One of the characteristics of the broad discussion of this theme was an escalation, without evidence, of the estimated numbers of homosexual victims of Nazism (a hundred thousand, a quarter of a million, half a million ... ), and a careless tendency to assume that the Nazis had prosecuted the same kind of campaign against homosexual men as they had against Jews, with the aim of total annihilation as a final solution to the homosexual problem. My feeling now is that such exaggerations were understandable and perhaps inevitable, given that most of us were hearing of the Nazi mistreatment of homosexual men for the first time and that few substantiating facts seemed to be available. Above all, in contrast to the Shoahthe Holocaust of the Jewsthis smaller catastrophe had apparently not been furnished with the narrative evidence of survivors. Jewish memoirs of survival had been coming into print ever since the war had ended. Where were the homosexual equivalents?

For lack of firsthand accounts, some writers began to try to build narratives of the homosexual experience under Nazism around fictional characters. The gay holocaust became one of the concerns of the British theatre group Gay Sweatshop. They addressed it in two plays, As Time Goes By by Noel Greig and Drew Griffiths (1977), and Bent by Martin Sherman (1979). The first of these has successive historical settings, in three main locations: London in the 1890s, Berlin in the 1930s, and New York City in 1969. The aim was to compare and contrast the effects historical circumstances have on gay subcultures and on individual gay men. In each case, police action against gay men leads to drastic outcomes: the London characters decide they must go into exile; the Berlin characters are caught between exile and the horrors, as yet unrealized, of the concentration camps; and the New York characters respond to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn by kicking off a riot, thereby giving spectacular impetus to the gay liberation movement.

In the manner of all of Gay Sweatshops playsperformances which were always followed by lively discussions with the audienceAs Time Goes By is agitprop drama with a clear political message, an argument against quietism and the closet. The characters who meet oppression with optimistic discretion, keeping their heads down and hoping for the best, tend not to do well from it: for their invisibility is no more acceptable to the authorities than the flamboyance of the drag queenand is hardly more secure. The argument is in favor of visibility, pride, and active resistance. The play recognizes that this may have been virtually impossible, except to a few extraordinary individuals, in 1890s London and 1930s Berlin (where the pioneering sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld is one of its characters); but in gay-liberationist New Yorkand, by implication, in the England in which the play was to be performedthere was no excuse for inaction or for staying in the closet.

On the use of Nazism as the context for the plays central section, Philip Osment, a playwright and director who worked with Gay Sweatshop, later wrote:

Even in 1977 there was a widely held belief that homosexuality had been somehow responsible for the Third Reich. The perverted brutality of that regime was often embodied in plays and films by the queer Brownshirt or SS guard. I remember friends who couldnt understand why Gay Sweatshop was doing a play about Nazi Germany asking, Werent most of the Nazis gay anyway? The fact that homosexuals were sent to the concentration camps was still not widely known and we were often left out when victims of the Holocaust were listed.

The post-war situation of German gay men and lesbians had been exacerbated by a homophobic mythology that had been built up by the propagandists of the anti-Nazi movement. The Nazis were themselves said to be homosexual perverts: hence the imagery of the Hitler Youth; hence also the tailored uniforms and jackboots. This has proved to be one of the most enduring of the myths about Nazism, all the more solidly endorsed whenever yet another biography of Hitler repeats unsubstantiated suggestions either that he was actively homosexual himself or at least that, by reason of poverty, he worked as a rent boy during his youth in Vienna. The need to prove the sexual perversion of Nazism as an ideology, and of its leaders (most of whom were, of course, conventionally heterosexual) as a psychological type, has clouded the clarity of the regimes anti-homosexual vigor.