Jonathan C. Slaght - Owls of the Eastern Ice

Here you can read online Jonathan C. Slaght - Owls of the Eastern Ice full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Owls of the Eastern Ice

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Owls of the Eastern Ice: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Owls of the Eastern Ice" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Owls of the Eastern Ice — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Owls of the Eastern Ice" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Karen

What was happening around us was unbelievable. The wind raged furiously, snapping tree branches and carrying them through the air huge old pines swayed back and forth as though they were thin-trunked saplings. And we could not see a thingnot the mountains, not the sky, not the ground. Everything had been enveloped by the blizzard We hunkered down in our tents and were intimidated into silence.

VLADIMIR ARSENYEV, 1921, Across the Ussuri Kray

Arsenyev (18721930) was an explorer, naturalist, and author of numerous texts describing the landscape, wildlife, and people of Primorye, Russia. He was one of the first Russians to venture into the forests described in this book.

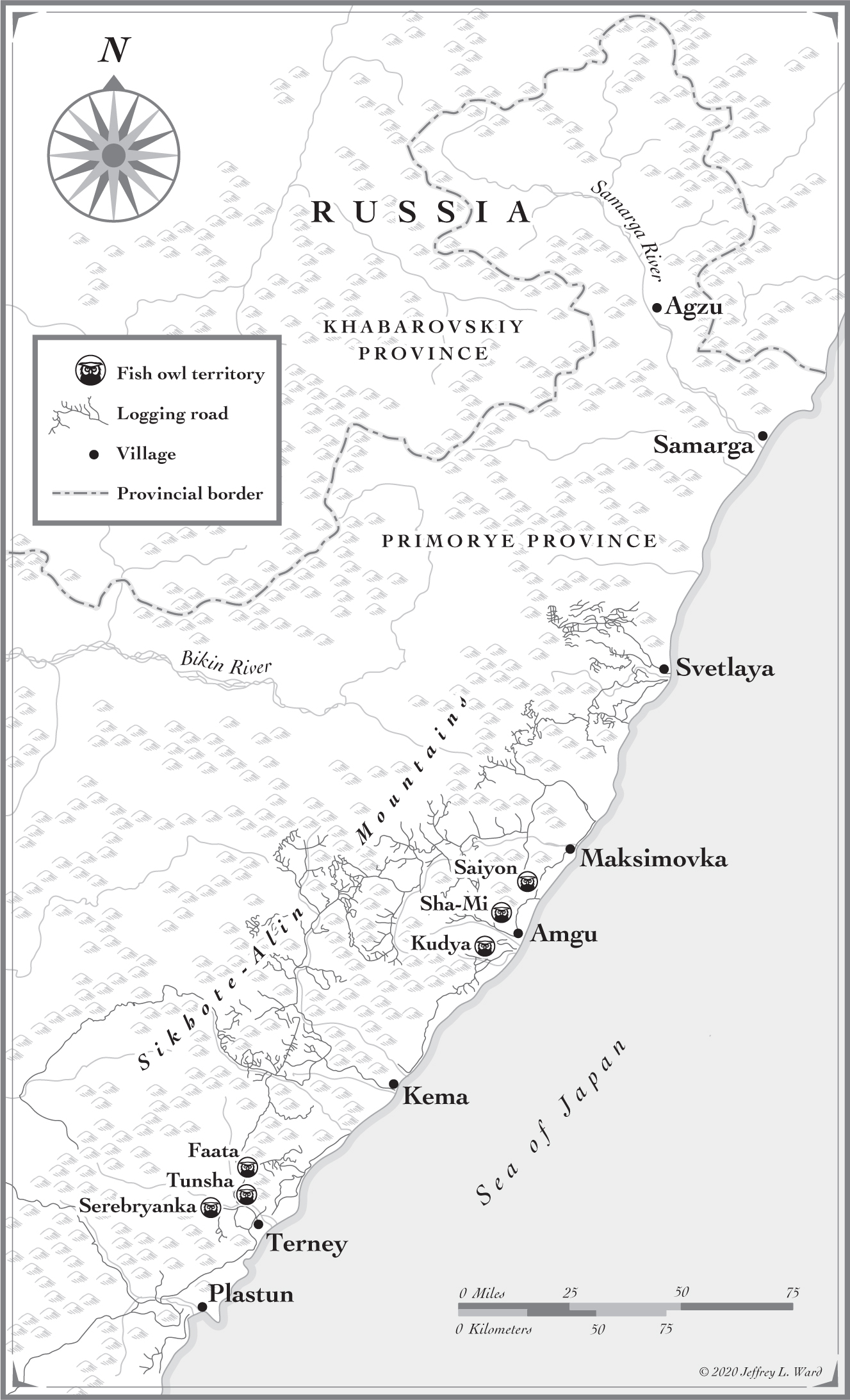

I SAW MY FIRST BLAKISTONS FISH OWL in the Russian province of Primorye, a coastal talon of land hooking south into the belly of Northeast Asia. This is a remote corner of the world, not far from where Russia, China, and North Korea meet in a tangle of mountains and barbed wire. On a hike in the forest there in 2000, a companion and I unexpectedly flushed an enormous and panicked bird. Taking to the air with labored flaps, it hooted its displeasure, then landed for a moment in the bare canopy perhaps a dozen meters above our heads. This disheveled mass of wood-chip brown regarded us warily with electric-yellow eyes. We were uncertain at first which bird, actually, wed come across. It was clearly an owl, but bigger than any Id seen, about the size of an eagle but fluffier and more portly, with enormous ear tufts. Backlit by the hazy gray of a winter sky, it seemed almost too big and too comical to be a real bird, as if someone had hastily glued fistfuls of feathers to a yearling bear, then propped the dazed beast in the tree. Having decided that we were a threat, the creature pivoted to escape, crashing through the trees as its two-meter wingspan clipped the lattice of branches. Flakes of displaced bark spiraled down as the bird flew out of sight.

Id been coming to Primorye for five years at this point. Id spent most of my early life in cities, and my vision of the world was dominated by human-crafted landscapes. Then, flying from Moscow the summer I was nineteen, accompanying my father on a business trip, I saw the sun glinting off a sea of rolling green mountains: lush, thick, and unbroken. Dramatic ridges rose high, then drooped into low valleys, waves that scrolled past for kilometer after kilometer as I watched, transfixed. I saw no villages, no roads, and no people. This was Primorye. I fell in love.

After that initial short visit, I returned to Primorye for six months of study as an undergraduate and then spent three years there in the Peace Corps. I was only a casual bird-watcher at first; it was a hobby Id picked up in college. Each trip to Russias Far East, however, fueled my fascination with Primoryes wildness. I became more interested and more focused on its birds. In the Peace Corps I befriended local ornithologists, further developed my Russian-language skills, and spent countless hours of my free time tagging along with them to learn birdsongs and assist on various research projects. This was when I saw my first fish owl and realized my pastime could become a profession.

Id known about fish owls for almost as long as Id known about Primorye. For me, fish owls were like a beautiful thought I couldnt quite articulate. They evoked the same wondrous longing as some distant place Id always wanted to visit but didnt really know much about. I pondered fish owls and felt cool from the canopy shadows they hid in and smelled moss clinging to riverside stones.

Immediately after scaring off the owl, I scanned through my dog-eared field guide, but no species seemed to fit. The fish owl painted there reminded me more of a dour trash can than the defiant, floppy goblin wed just seen, and neither matched the fish owl in my mind. I didnt have to guess too long about what species Id spotted, though: Id taken photos. My grainy shots eventually made their way to an ornithologist in Vladivostok named Sergey Surmach, the only person working with fish owls in the region. It turned out that no scientist had seen a Blakistons fish owl so far south in a hundred years, and my photographs were evidence that this rare, reclusive species still persisted.

AFTER COMPLETING A MASTER OF SCIENCE PROJECT at the University of Minnesota in 2005, studying the impacts of logging on Primoryes songbirds, I began brainstorming for a Ph.D. topic in the region as well. I was interested in something with broad conservation impact and quickly narrowed my species contenders to the hooded crane and the fish owl. These were the two least-studied and most charismatic birds in the province. I was drawn more to fish owls but, given the lack of information about them, was worried that these birds might almost be too scarce to study. Around the time of my deliberations, I happened to spend a few days hiking through a larch bog, an open, damp landscape with an even spacing of spindly trees above a thick carpet of fragrant Labrador tea. At first I found this setting lovely, but after a while, with nowhere to hide from the sun, a headache from the oppressive aroma of Labrador tea, and biting insects descending in clouds, Id had enough. Then it hit me: this was hooded crane habitat. The fish owl might be rare, devoting time and energy to it might be a gamble, but at least I would not have to spend the next five years slogging through larch bogs. I went with fish owls.

Given its reputation as a hearty creature in an inhospitable environment, the fish owl is a symbol of Primoryes wilderness almost as much as the Amur (also called Siberian) tiger. While these two species share the same forests and are both endangered, far less is known about the lives of the feathered salmon eaters. A fish owl nest was not discovered in Russia until 1971, and by the 1980s there were thought to be no more than three hundred to four hundred pairs of fish owls in the entire country. There were serious concerns for their future. Other than the fact that fish owls seemed to need big trees to nest in, and fish-rich rivers to feed from, not much was known about them.

Across the sea in Japan, just a few hundred kilometers east, fish owls had been reduced to fewer than one hundred birds by the early 1980s, down from approximately five hundred pairs at the end of the nineteenth century. This beleaguered population lost nesting habitat to logging and food to construction of downstream dams that blocked salmon migration up rivers. Fish owls of Primorye had been shielded from a similar fate by Soviet inertia, poor infrastructure, and a low human population density. But the free market that emerged in the 1990s bred wealth, corruption, and a covetous eye focused keenly on the untouched natural resources in northern Primoryethought to be the fish owls global stronghold.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Owls of the Eastern Ice»

Look at similar books to Owls of the Eastern Ice. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Owls of the Eastern Ice and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.