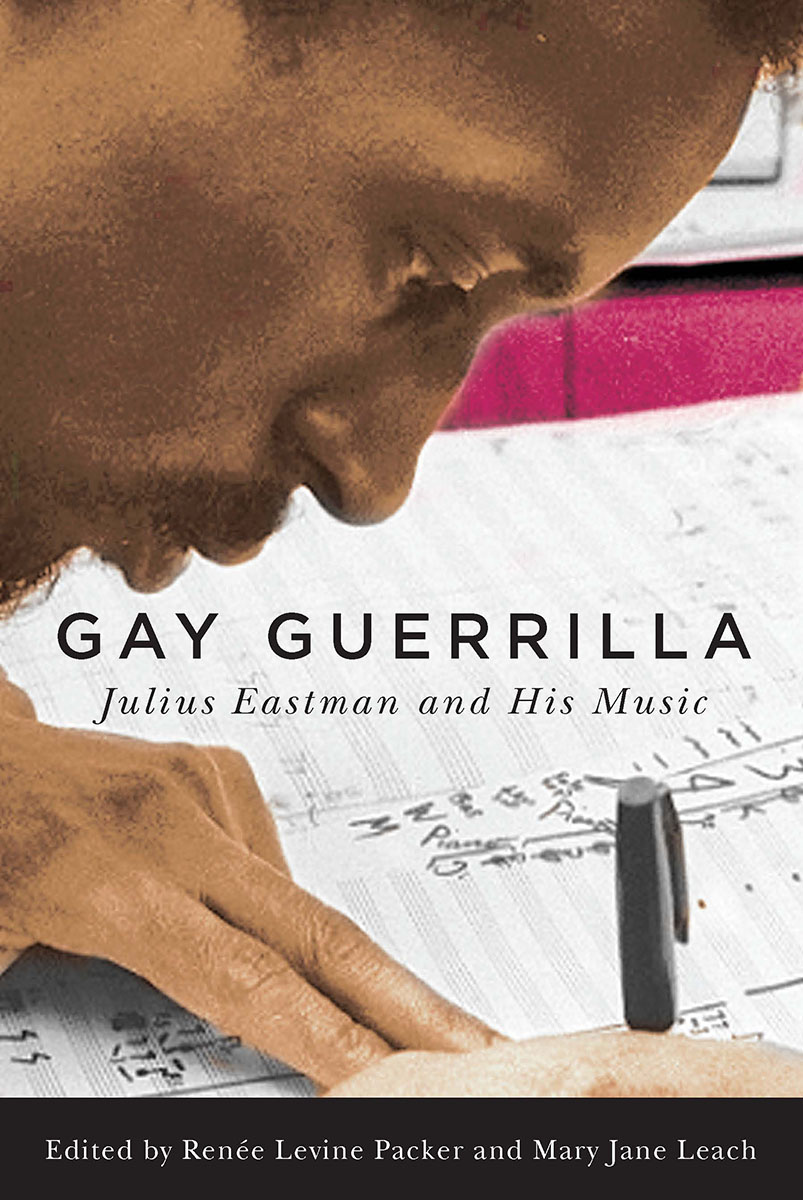

GAY GUERRILLA

Composer-performer Julius Eastman (1940-90) was an enigma, both comfortable and uncomfortable in the many worlds he inhabited: black, white, gay, straight, classical music, disco, academia, and downtown New York. His music, insistent and straightforward, resists labels and seethes with a tension that resonates with musicians, scholars, and audiences today. Eastmans provocative titles, including Gay Guerrilla , Evil Nigger , Crazy Nigger , and others assault us with his obsessions.

Eastman tested limits with his political aggressiveness, as recounted in legendary scandals he unleashed like his June 1975 performance of John Cages Song Books , which featured homoerotic interjections, or the uproar over his titles at Northwestern University. These episodes are examples of Eastmans persistence in pushing the limits of the acceptable in the highly charged arenas of sexual and civil rights.

In addition to analyses of Eastmans music, the essays in Gay Guerrilla provide background on his remarkable life history and the eras social landscape. The book presents an authentic portrait of a notable American artist that is compelling reading for the general reader as well as scholars interested in twentieth-century American music, American studies, gay rights, and civil rights.

Contributors: David Borden, Luciano Chessa, Ryan Dohoney, Kyle Gann, Andrew Hanson-Dvoracek, R. Nemo Hill, Mary Jane Leach, Rene Levine Packer, George E. Lewis, Matthew Mendez, John Patrick Thomas.

Rene Levine Packers book This Life of Sounds: Evenings for New Music in Buffalo received an ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for excellence. Mary Jane Leach is a composer and freelance writer, currently writing music and theatre criticism for the Albany Times-Union .

CONTENTS

Rene Levine Packer

Rene Levine Packer

David Borden

R. Nemo Hill

Kyle Gann

John Patrick Thomas

Mary Jane Leach

Ryan Dohoney

David Borden

Andrew Hanson-Dvoracek

Matthew Mendez

Mary Jane Leach

Luciano Chessa

Mary Jane Leach

FOREWORD

George E. Lewis

T his volume constitutes an early and signal contribution to the growing corpus of scholarship and commentary on the music of the composer and singer Julius Eastman. The individual essays confront the several challenges Eastmans life and work pose to canonical narratives of American experimental music. This book is the result of the combined tenacity of its two coeditors. First, there is Rene Levine Packer, a chronicler of late twentieth-century American experimental music who knew Eastman since his early days as a Creative Associate at the University at Buffalo. The other driving force behind this book is the composer Mary Jane Leach, a central figure in Downtown experimentalism, whose relentless musicological sleuthing has been crucial to unearthing new knowledge about Eastmans life and work.

Leachs experiences while researching Eastman included unusual dreams and inexplicably malfunctioning software that did not allow her to read e-mails associated with the project. I began to wonder, Leach recalls, if Eastmans spirit was trying to sabotage the dissemination of his music. Strange things began to happen to Kelley as he pursued knowledge about Monk, culminating in a hit-and-run car accident that left him with severely reduced mobility for months. Kelley told a friend that he was wondering if Monk were somehow involved in what was happening to him. The friend responded, Did you ask Theloniouss permission to write the book? Kelley decided to create an atmosphere that would allow him to make that request, and somehow, the strange occurrences came to an end. The possibility that Eastman could be similarly contacted through spiritual methodologies seems less odd when we consider the extent to which, as this book shows, a kind of pan-religious spirituality and ethics often permeated encounters with Eastman and his work.

Most of the contributors to this book, including me, actually met Eastman at some point in his turbulent career. I do not quite remember when I met Julius for the first time, and for reasons that I hope will become clearer later, I will refer to him by first name just this once. As someone who came of musical age in part in several Downtown New York music scenes in the late 1970s, I have my own reminiscences about Julius, some of which go back to my attendance at live performances of his work. Other traces of memory remain from the fall 1980 Kitchen tour of Berlin, Stockholm, Paris, and Eindhoven, in which I participated along with Douglas Ewart, Eric Bogosian, Robert Longo, Molissa Fenley, Rhys Chatham, Joe Hannan, Bill T. Jones, Arnie Zane, and others.

Prior to Eastmans emergence, the African-American presence in the Downtown New York music scene of the 1960s and 1970s was marked by two important figures: the composer and artist Benjamin Patterson, a key figure in the Fluxus movement, and the composer Carman Moore, who in the early 1960s founded the Village Voice s tradition of a regular, composer-written column on new music, providing important early exposure for colleagues such as La Monte Young. As this book shows, Eastman was a prominent member of this scene; his collaborators, colleagues, and associates comprise a Whos Who of American experimentalism.

For me, Eastman represented a singular figure of presence; as a newcomer to New York in 1975, I did not know Moore, and Patterson appeared to me as a legend living in Germany.

A recent article by Hisama calls on scholars to apprehend Eastmans work as a black, gay man who worked in a primarily white new music scene... with respect to both of these social categories, rather than to disregard them within a post-race or sexuality-neutral context. Eastman himself issued an explicit call, avant la lettre, for this kind of intersectionality, with the notorious title of one of his works: Nigger Faggot (1978). Once again, we can point to African-American letters for antecedents, notably in the work of James Baldwin, and afterward, in the work of Marlon Riggs and the gay-sibling artists Thomas Allen Harris and Lyle Ashton Harris.

This presents us with at least two axes of interpretation, but to claim that both were equally mediational would warp the case. Though sexual acts between consenting adults of the same sex were illegal in the United States until late in the twentieth century, homosexuality could nonetheless be acknowledged and even quietly celebrated across large swatches of the art world. The same could not be said of blackness; black artists were far less in evidence in the Downtown New York music scene than queer ones, and one could never be quite sure when the products of backgrounds similar in most details to Eastmans might suddenly be denigrated (in the exact sense of that term), either openly or cryptically.

None of the authors in this volume identify any instances where homophobia posed an issue of collegiality for Eastman in the new music scene; indeed, his alliances with other emerging gay composers of his approximate generation, such as Arthur Russell, indicate that there was a considerably more extensive network of gay artists in this scene than of African-American artists. Eastmans home and public lives, however, were another matter. According to Hisama, Eastmans mother was accepting of his sexual identity, and disturbed by his fathers lack of accommodation to it.

The protest against the titles of the pieces on a controversial 1980 Northwestern University concert of Eastmans music resulted in their eventual removal from the printed concert program.