Contents

Guide

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2020 by Title TK Projects, LLC

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition August 2020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Carly Loman

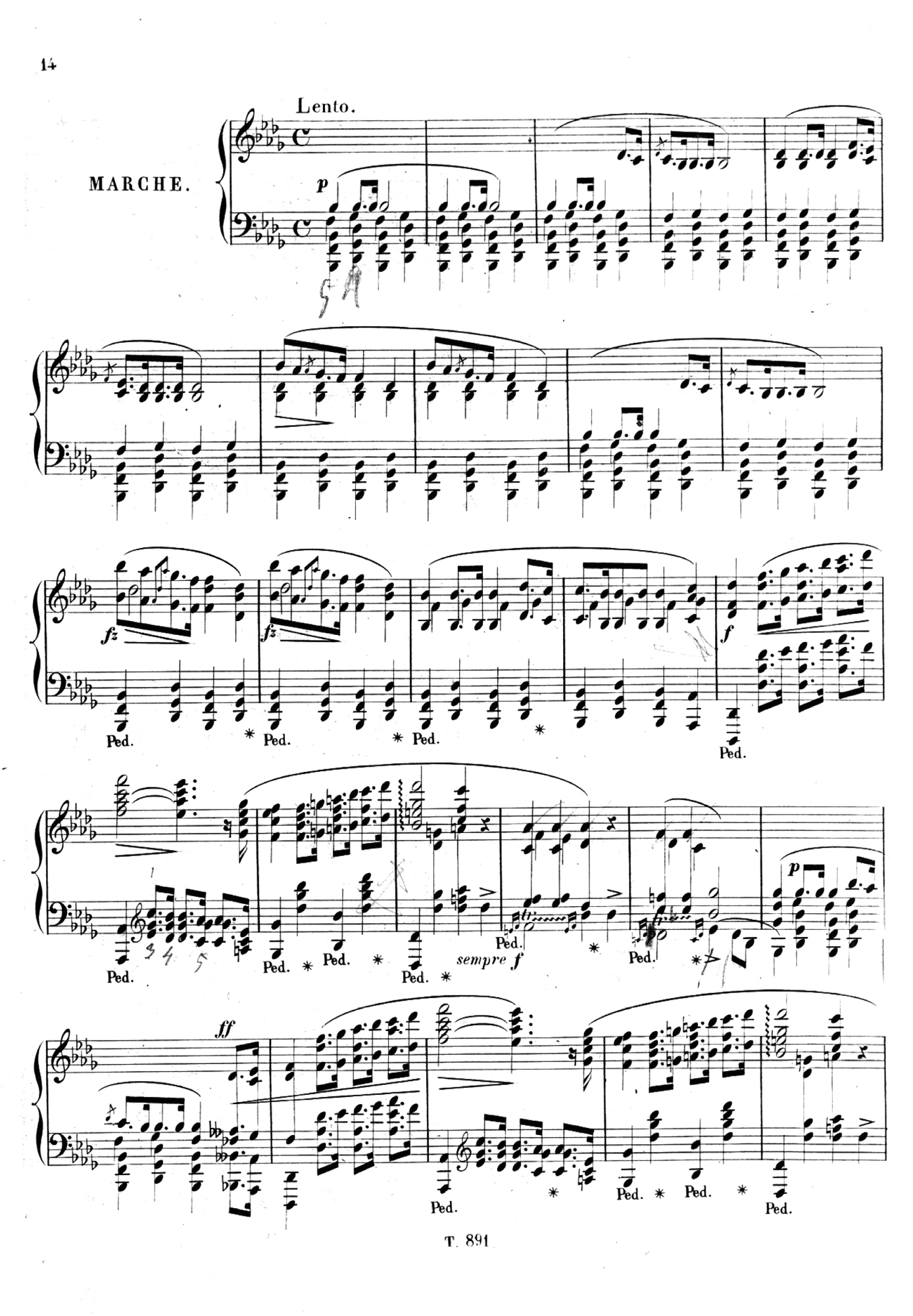

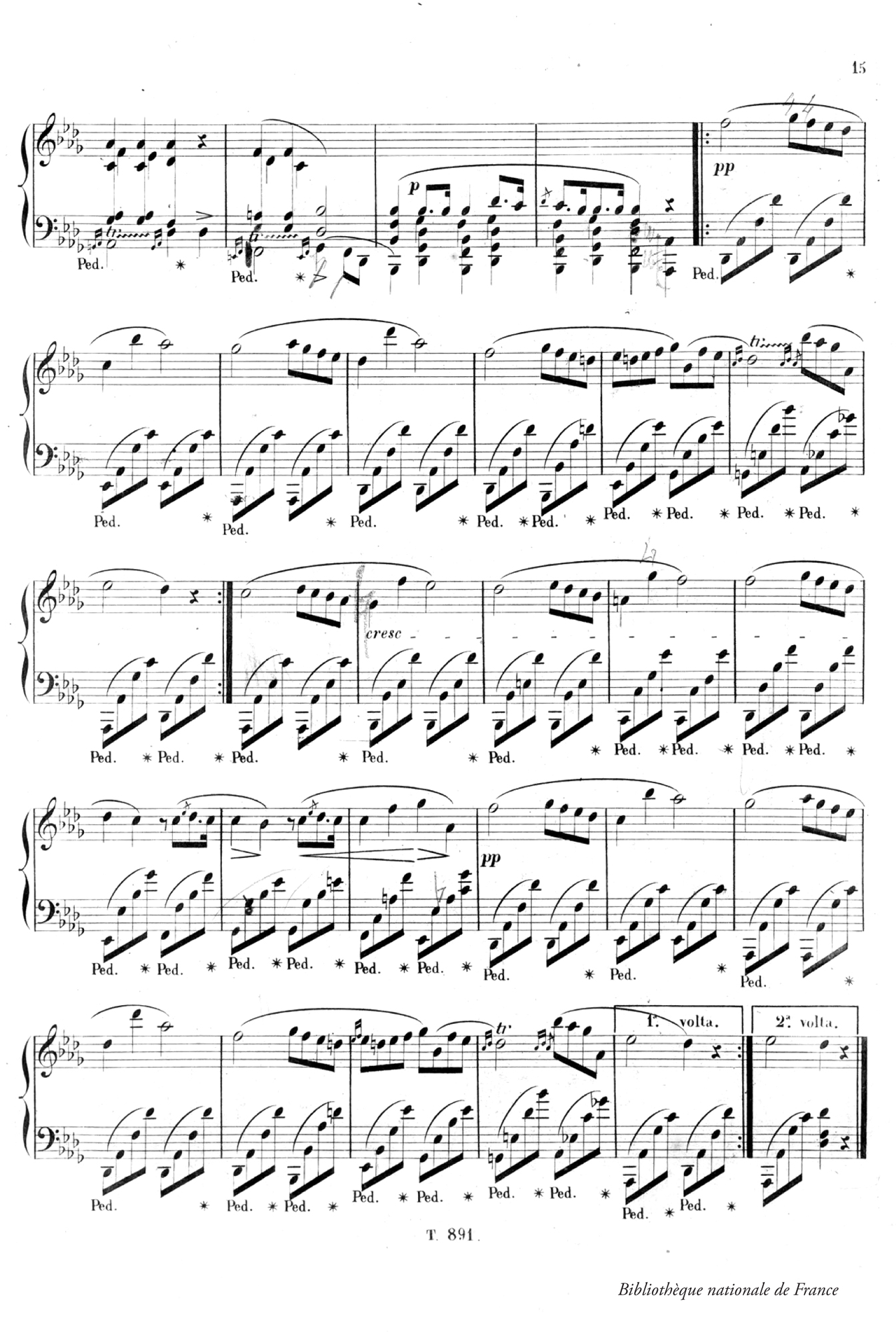

Transcription and music graphic on the dedication page2020 by Oliver Kwapis (BMI)

Hand-Lettering by Tyler Comrie

Illustration by Piotr Micherewicz, a Distinction in the Ams Poster Gallery Competition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: LaFarge, Annik, author.

Title: Chasing Chopin : a musical journey across three centuries, four countries, and a half-dozen revolutions / by Annik LaFarge

Description: New York : Simon & Schuster, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019049711 | ISBN 9781501188718 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501188732 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Chopin, Frdric, 18101849. | Chopin, Frdric, 18101849. Sonatas, piano, no. 2, op. 35, B minor.

minor.

Classification: LCC ML410.C54 L195 2020 | DDC 786.2092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019049711

ISBN 978-1-5011-8871-8

ISBN 978-1-5011-8873-2 (ebook)

Illustration Credits

: Bibliothque Nationale de France

for Ann

AUTHORS NOTE Dancing About Architecture

Almost immediately after I began working on this book, I stumbled on an old clich that will resonate with anyone who has ever tried to explain in words what a piece of music means to them: Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.

No one seems to know who said it first, but the statement stuck around because it so perfectly captures the challenge. Music is an abstract art form, one that exists in time, is defined by mathematics, and is written in a complex language that consists of symbols, numbers, a horizontal grid, and emotion-laden words in (usually) Italian. If I were getting ready to tell you a story about a work of art, I would insertprobably right below this sentencean image. That would give you an immediate context for what comes next, something to hold in your mind as you read about the people, places, and events, as well as the joys and sorrows, that animate my subject. But musical notation in the pages of a book like this, one that attempts to tell a human story about the creative process, would be useless to all but the most expert of readers. So to help bridge the gap between words and music I built a companion website that makes it easy to find and listen to the works of Chopin, as well as the many other composers who become relevant in the story, from J. S. Bach to Cole Porter.

The site, which lives at www.whychopin.com, is accessible in any Web browser and is organized more like a book than a traditional website. Each chapter of Chasing Chopin has a section, or web page, where links to recordings (along with basic information like the title of a piece, its opus number and date of composition) are listed in the order in which they appear in the text, along with the page number for easy reference. Sometimes there are two links for a single work, so a reader can hear the same piece of music as its played on both a modern Steinway and a nineteenth-century pianoforte. This is because I spend a good deal of time talking about the pianos that were available during Chopins lifetime, and the many differences between them and the instrument we know todaythings that actually affect the way we perceive the music. This allows a reader to experience what is the closest we can come to a nineteenth-century soundscape, when recording technology didnt exist, and compare it to the sound a modern artist might produce at Carnegie Hall or on National Public Radio. There are also links to a wide variety of interpretations of Chopins work in jazz, modern song, and popular culture, along with photography and video from my travels; scholarly and popular resources; and more.

One of the first links on WhyChopin.com is to a recording of the funeral march from Chopins Opus 35 Sonata, whose composition story constitutes the narrative arc of this book. What you hear first is the familiar dirgedum dum da dumwritten in the key of B-flat minor. Then comes the surprising and beautiful major-key interlude (in D flat), which is in turn followed by an inexorable return of the minor-key dirge. Its this modulation, the striking progression from minor to major to minor, that I would illustrate with an image if I could. Its at the heart of the story Im about to tell, and is what astonished me the first time I heard the sonata, and inspired me to learn more about the man who conceived it and the circumstances in which he wrote and lived. Even if you know absolutely nothing about music, I think you will hear what captivated me in this startling, original statement about death and life.

Of course the website is not necessary; its just a tool, something that might enhance a readers experience by making it easy to access the best, and in some cases inaccessible, recordings. Beyond a few observations in the opening pages about the two sections of the funeral march, theres very little technical or theoretical stuff in the pages ahead; its mostly, in effect, a love story, one that connects humans to one another, and all of us to art. But if you do come across a term that feels foreign or confusing, my advice is to just skip over it and keep reading. Or, better yet, get up and dance about it.

INTRODUCTION Bulls-eye

Music is often the language we speak when we speak about death. My father was a poet and playwright, but when he became so ill it was clear the end was near, it was music that was on his mind, not words. The only request he made was that, after he died, we let his body remain on the hospital bed in his room and fill the house with music for twenty-four hours before the undertaker came. It was Bachs Suites for Unaccompanied Cello that he requested, and so someone in the family who had a basic level of technical expertise figured out how to put the six suites, played by Pablo Casals, into a continuous loop. All day and all night, as people came and went, slept and wept, talked and laughed, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach permeated every room of the house, offering a kind of structure to those many minutes and hours of our collective grief. It also, and this came to me as I sat on the stairs leading up to my fathers bedroom that crisp, sunny, late October morning, served to connect us, not just to him but to each other. Music, unlike poetry, requires other humans to animate it from the page. Whether you play for one person or many, it is at some level an affair of the community, something we do together to bring a bit of beauty and meaning into our lives. It also reminds us, especially at times around death and dying, of what connects us. This is because music needs both a player

minor.

minor.