INTRODUCTION

The smoke clouds of war slowly began to dissipate and the spring sun broke through, caressing the ruins that buried tens of thousands of human beings, flooding the devastated streets, and scattering sparks of light on the waters of the broad Vistula River that slowly bubbled up to wash away memories of dread and death.

On the hill, above scarred Warsaw, stood the ancient and magnificent mansion of the Stolowitzky family, which had miraculously survived the war intact. Four floors of hewn stone, carved edges, statues of ancient warriors on the roof ledge, impressive mosaic windows and painted wooden ceilings.

Only two of the original inhabitants of the mansion were still alive, a boy and his nanny, and they were on their way to another country, far away. In their new home, between peeling walls, rust spots spreading in the bathtub, and cheap furniturethat mansion with all its splendor and charm seemed like a daydream, the product of an overactive imagination.

The boy and his nanny, who adopted him as a son, lived in a small apartment in one of the alleys of Jaffa, in a tenement. From the window, they saw only dreary buildings, children playing in an abandoned yard, and women returning home from the market, carrying heavy shopping bags. Most of the day, the apartment was invaded by the noise of passing cars and the stench of garbage. In winter the smell of mildew permeated the rooms, and in summer the walls trapped a blazing stifling air.

In the mansion on the hill, everything, of course, was different. The big building with its spacious wings, its gardens, was properly heated in winter and properly cooled in summer. A pure breeze from the river blew in the windows and servants tiptoed about to avoid any undue noise. The closets were stuffed with expensive clothes. Luxurious meals were served in rare china dishes. The old heavy cutlery, polished clean, was gold, and the wine was poured into fine crystal glasses.

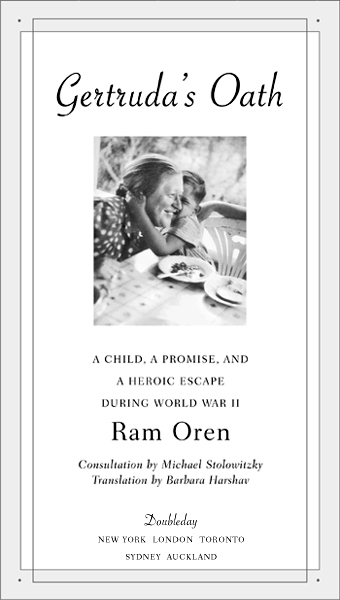

Michael Stolowitzky and his adoptive mother, Gertruda, had survived the war and now both of them were struggling to survive in the new land. He attended school. She was past her prime by now. Every morning shed go to work as a cleaning woman in the northern part of the city and return in the evening, her joints aching and her eyes weary. Michael would greet her with a kiss, take off her shoes, cook her meager supper, and make her bed. He knew she was working too hard only to have enough money to send him to school and provide for all his needs. He swore that someday he would pay her back generously for everything she had done for himfor saving him from death, for devoting her life to him, for making sure he didnt lack anything.

Poverty and shortages werent strangers to Michael Stolowitzky. He had experienced them throughout his journey of survival in the world war, but he also saw light at the end of the tunnel, the end of penury, the end of the daily struggle for existence. He believed that someday, in the not-too-distant future, everything would change and things would go back to the way they were, to the days when they knew wealth and comfort, days far from suffering and torments.

His rosy future was within reach, clear and concrete. Only a four-hour flight from Israel lay a blocked treasure, millions of dollars and gold bars deposited in Swiss banks by his late father, Jacob, the Jew who was called the Rockefeller of Poland. Michael was his only heir.

The legacy, a small recompense for the suffering and loss of the war, filled Michaels thoughts and assumed a central place in his fantasies. When he was recruited into the Israeli army, he waited impatiently for his military service to end so he could work on getting the money. He was sent to a battle unit and was wounded in the leg by a bullet from a Syrian sniper during a firefight in the northern Kinneret.

Groaning in pain, he was taken to the operating room in the hospital in Poriya. When he opened his eyes after the anesthesia wore off, he saw his adoptive mother weeping. He held his weak hand to her and she clutched it to her bosom.

Dont cry, he said. I promise you that everything will be fine.

When he was discharged from the army, he returned to their small apartment and the very next day he went to look for work. No work was beneath him. He was a messenger on a scooter, running around all hours of the day among customers in Tel Aviv; he worked as a waiter in the evening; and he was a guard at a textile factory at night. It was important for him to save up money.

Two years later, in June 1958, he took all his savings and the surviving family documents and bought an airplane ticket to Zurich.

How long will you be there? asked Gertruda anxiously.

Two or three days. I dont think Ill have to stay any longer than that.

And if they wont give you the money?

He smiled at her confidently. Why wont they? Youll see, Ill come back with my inheritance and our whole life will change, he promised.

She went to the airport with him and kissed him good-bye.

Take care of yourself, she said. And take care of the money. Dont let them steal it from you.

Dont worry, he replied.

He got on the plane, excited and anxious. In Zurich he rented a small room and couldnt fall asleep all night. He had only the name of one bank among those where his father had deposited his funds, and the next day he went there. He pictured the bank clerks bringing him heaps of money and his adoptive mother welcoming him when he got back to Israel, rich and carefree. He knew exactly what he would say to her:

Were rich, Gertruda. Now well move to our own house, well buy whatever we want, and most importantyou wont ever have to work again.