two of the women I love.

Words to live by

Let us not waste our time in idle discourse! Let us do something, while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed. Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate consigned us! What do you say?

Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot , 1953

Grand things are ahead. Worth living, and worth dying for.

Ascribed to Jack Reed in the movie Reds , 1981

Let us roll all our strength and all

Our sweetness up into one ball,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Thorough the iron gates of life:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.

Andrew Marvell, To His Coy Mistress, c1650

I found that the written word could achieve far greater disturbance than planting a bomb in a supermarket. The written words a powerful thing and I dont think that was too well considered, at least not in pop music, until I started to write that way.

John Lydon aka Johnny Rotten, Anger Is an Energy: My life uncensored , 2014

Arise, ye workers from your slumber,

Arise, ye prisoners of want.

For reason in revolt now thunders,

and at last ends the age of cant!

Away with all your superstitions,

Servile masses, arise, arise!

Well change henceforth the old tradition,

And spurn the dust to win the prize!

Traditional British version of The Internationale, Eugene Pottier, 1871

Opening remarks : the end at the beginning

But our beginnings never know our ends!

T S Eliot, Portrait of a Lady

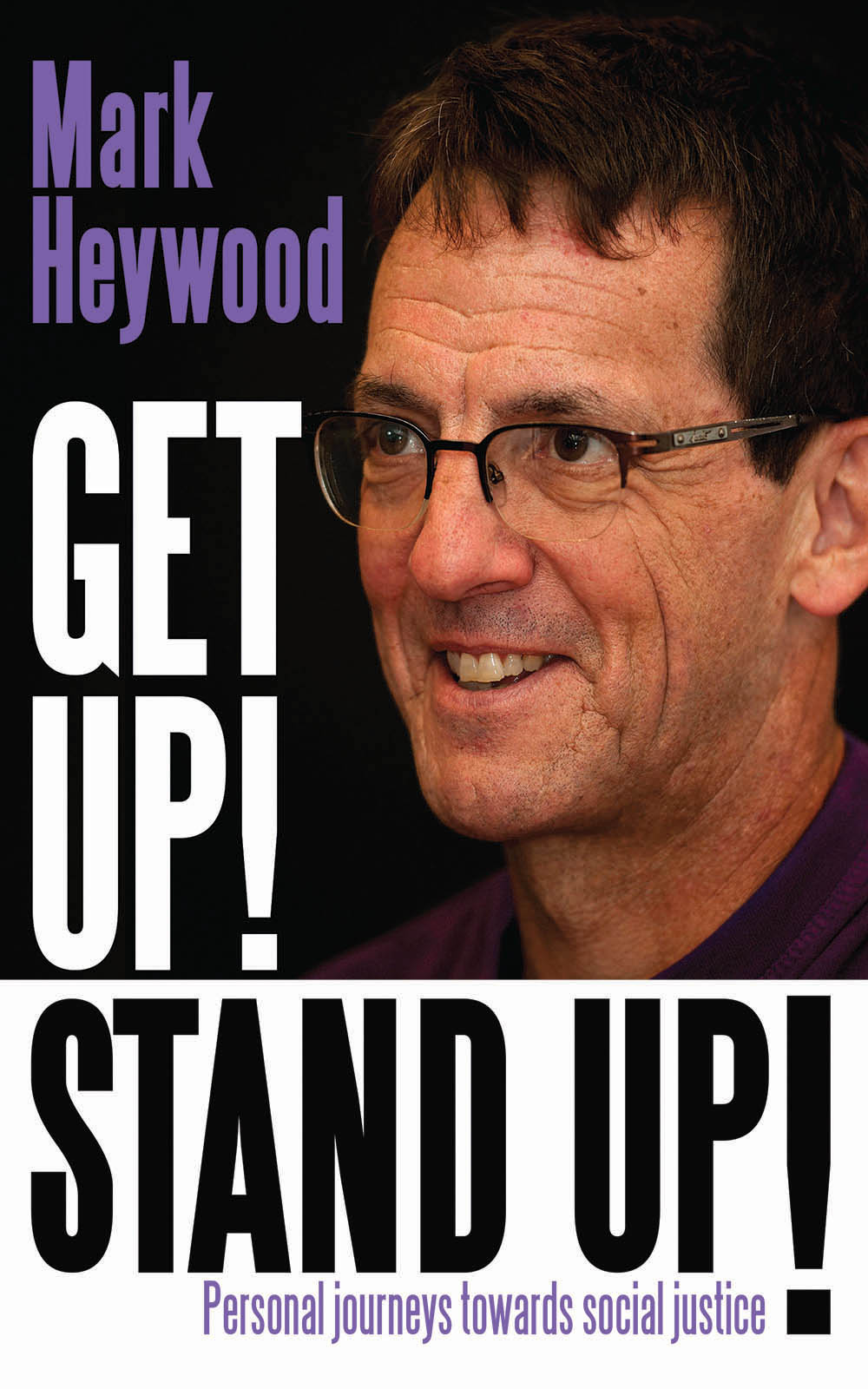

This book is about how politics, love, literature and song intertwine and shape consciousness and commitment. It is about how revolutions are made not simply by passion, but also by art and books and friendship.

In the past great freedom struggles were carried forward by hope. Activists shouldered the real possibilities of death, torture, lengthy imprisonment because they had an abiding hope. They believed in the morality of justice. So the question this book explores is whether good people today still have hope in their arsenal.

I have always been concerned with social justice, yet in recent years I have seen hope begin to fade. And so the core question facing many people who continue to care about our collective future is not Should we hope? but On what can we base our hope? How can we retrieve the promise of democracy and the stolen dream of equality?

Today we have the misfortune of being able to look forward into politics and the future trajectory of our societies with far more clarity than anyone could have done 50 years ago. Of course there are many great unknowns. But to the question Will life get any better for the poor and for the people without monetary power? the inescapable answer seems to be no if, that is, we continue to feel powerless in the face of the politics of the present.

Why do we feel so debilitated when so many people have so much knowledge of the crisis of human civilisation that has come into being? Has there been a loss of hope?

I started this book on 27 March 2014, thinking while sitting atop a fortress whose remnants date back centuries. The fortress is on the property of the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center in Bellagio in northern Italy. Visible from its ancient stone ramparts, in the far distance were smooth white snow-slopes on a range of mountains whose individual names I do not know, but whose collective grandeur has long been described as the Alps. Below me lay Lake Como shining in the sun, a deep, variegated blue-green, its surface occasionally broken by the wake trailing one of the ferries which cross from one side to the other numerous times a day. A sprinkling of villages along the waters edge showed signs of life a train cutting along the mountain-side, chimneys puffing smoke. About and above me, a cold March air, clouds that thickened and then thinned again, the small-talk twitter of a band of birds, including a single woodpecker.

The idea of writing a book was of course intimidating especially a book about justice and hope.

I wanted to start with the great beauty of living and the potential beauty of the human being. Academics and historians debate what it was that marked the dawn of civilisation, but however you date it, after thousands of years the world has become a very civilised place and human beings enormously sophisticated. Generation after generation of humans, age after age, have accumulated knowledge of themselves, their world, their universe, science, shortcuts and long-cuts, technologies, their own physiology, the human genome.

For those who can benefit from this knowledge and this will be my theme the world offers a vast accumulation of riches.

Yet, as we know, far too many people cannot benefit from all that we have accumulated and all that we know.

This disparity the inequality that grows and grows and the sense of helplessness that too many people feel as they face it are the subjects of this book. It is no wonder then that it has taken three years to complete. I was nave when I sat down to write it on that first day in Bellagio.

By my last day I knew that the task was far larger and more significant than I had understood. On that day the clouds came down, miraculously materialising out of the blue skies that had persisted for days. For weeks I had watched the snow retreat from the mountain-tops as spring advanced. But on that day the upper hills were dusted with new snow, while everything below was cloaked in a sombre, silent and pondering grey, making it a day for introspection.

I looked back on days of mental wrestling and realised that although A Book was still playing hard to get, it was beginning to struggle through the millions of words from which we make meaning, our multiple analyses and ways of looking at the world.

I returned to South Africa and submitted the manuscript as it then stood to a publisher. Several weeks later the return-to-sender came, accompanied by a letter from Tony Morphet, the publishers reader, that described it as dry and drab, overly polemical and mildly didactic. A year later I started writing again, taking as my cue Morphets suggestion that the one part that had excited him was where I wrote about my personal experience of working in London with the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC. Up to that point I had resisted writing about myself and my own experience, but I decided to give it a try. This time the words flowed freely. Looking back over them, I realised that I had told a personal story about politics.

But now I also realise more clearly than ever before that politics can be understood only through personal experiences, mine and many others. Politics is not an aloof science that can be described as if it unfolds according to objectively established laws. It is the accumulation of personal experiences, the degree to which people engage with their world in order to change it.

I love books. I love words. But when I started to write this book I felt angry with book-writers. So many word-weavers abuse their gift by writing abstrusely and obscurely. Consequently, the people who may benefit from their thoughts the people who need their thoughts are not able to comprehend their words and what they tell us about this world.