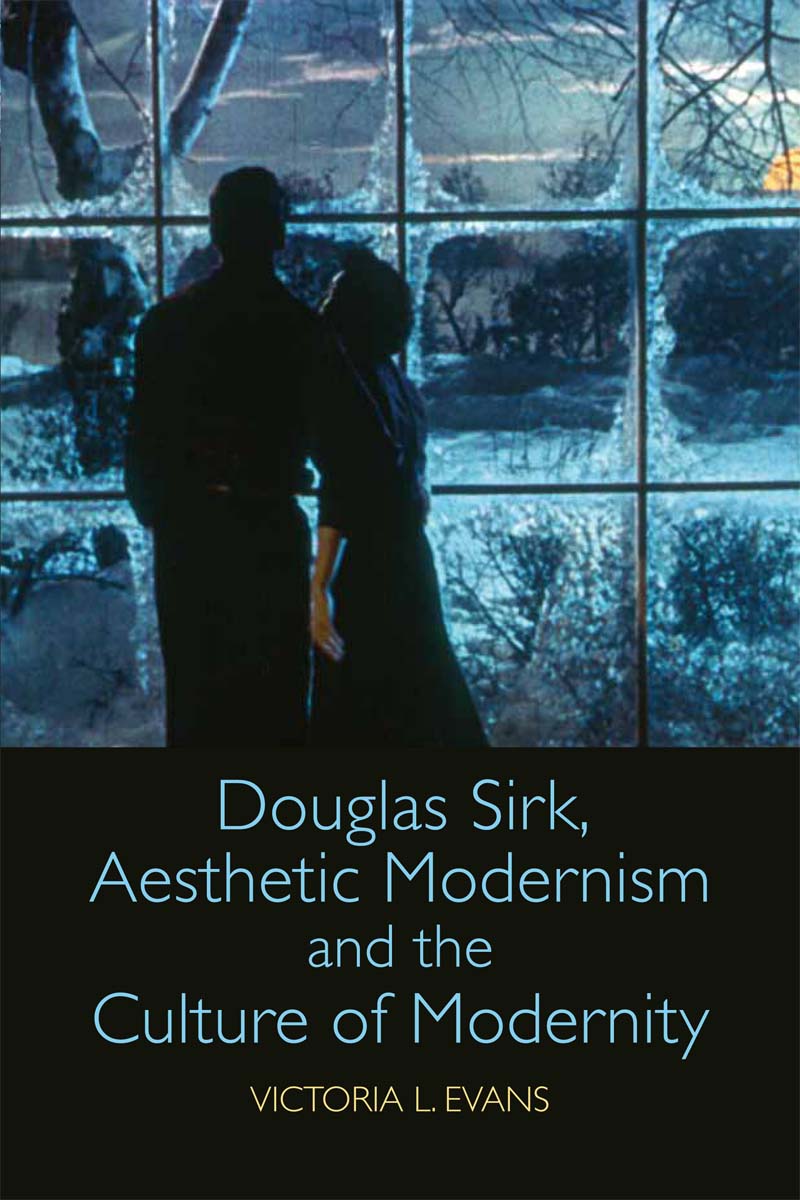

Douglas Sirk, Aesthetic Modernism and the Culture of Modernity

Douglas Sirk,

Aesthetic Modernism and the

Culture of Modernity

Victoria L. Evans

Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com

Victoria L. Evans, 2017

Edinburgh University Press Ltd

The Tun Holyrood Road

12 (2f) Jacksons Entry

Edinburgh EH8 8PJ

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4744 0941 4 (epub)

The right of Victoria L. Evans to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498).

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the many people who have provided me with intellectual or emotional support during the long process of bringing this highly interdisciplinary project to fruition. In particular, I would like to thank Stephanie Brge, Catherine Fowler, Alistair Fox, David Gerstner, Ross Gibson, Gillian Leslie, Sally Milner, Hilary Radner, Bettina Senff and Erika Wolf. Since some of my insights have been grounded in the information that is contained in a number of unpublished documents, I would especially like to thank the two archivists who assisted me in finding them, Ned Comstock of the Doheny Librarys Department of Special Collections (University of Southern California, Los Angeles) and the late Charles Silver (Museum of Modern Art, New York). My long-suffering partner, Michael Robertson, deserves a special mention for his unwavering faith in my ability to complete this project and his abiding love, which I have crossed two oceans to keep.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of three people who will always be important to me: Zdenka Volavka, who first sparked my interest in aesthetic Modernism at York University (Toronto), Joseph Camacho, a documentary maker who taught me that film could be an instrument for social good, and my mother, Betty Louise Evans.

Introduction

In a 1994 interview entitled Beyond Cinema, Peter Greenaway spoke of his growing frustration at having to work within the spatial and temporal constraints imposed by the two-hour-long narrative film. By erecting one hundred staircases topped with viewing platforms all across the city of Geneva for an art exhibition that was scheduled to last one hundred days, he was endeavouring to take the concept of the frame out of cinema and place it in a more public situation allowing for the possibility of a 24-hour continual viewfinder. However, more than four decades before Greenaways urban installation or the advent of the digital age, Douglas Sirk was already attempting to dissolve the limits of the cinematic medium by assimilating elements of avant-garde art, architecture and design into the mise-en-scne of many of his best-known films.

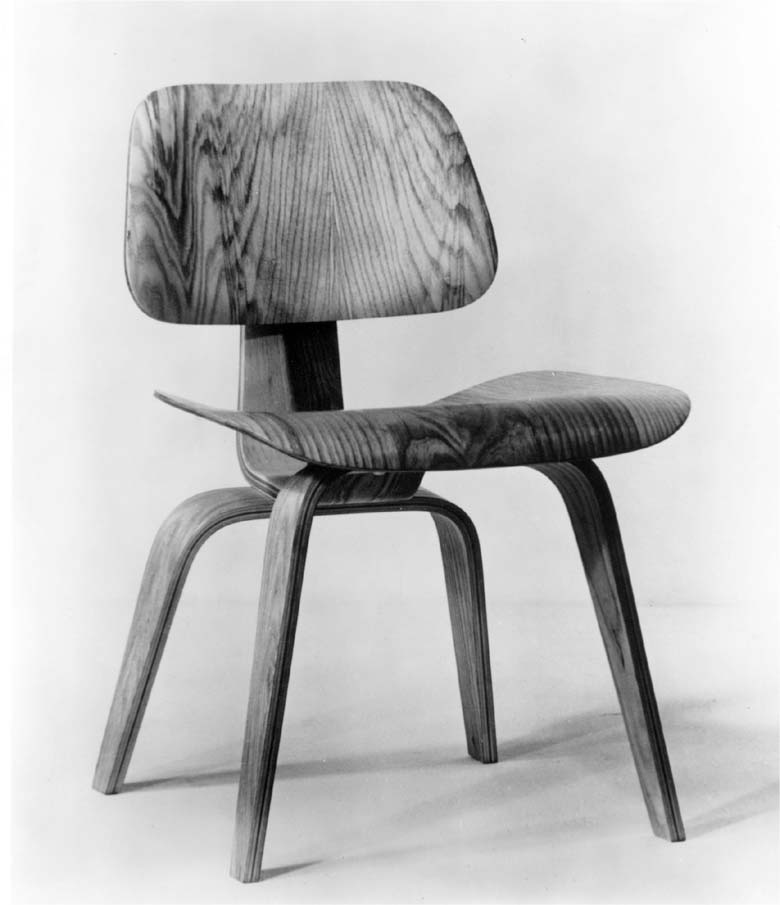

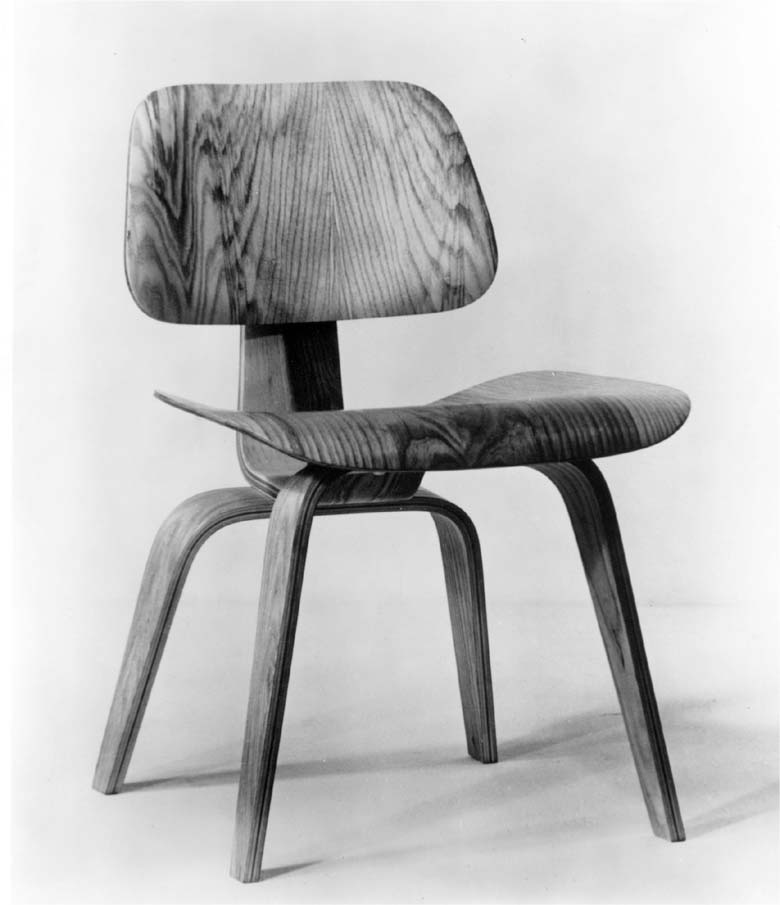

Sirks importation of a high art aesthetic into the low genre of melodrama echoed the widespread European Modernist preoccupation with the creation of a synergistic Gesamtkunstwerk or total art work during the period in which he intellectually came of age. For the full duration of this sequence, one or more of these skittish-looking mid-century Modernist masterpieces may be observed alongside the blind womans face or body almost every time she appears in the frame. By the final scene of the film, when the ailing widows health and sight have been miraculously restored in a white-walled room that was often suffused with a very non-naturalistic blue light, I was utterly intrigued. What is the meaning of these intimations of an extra-filmic artistic vanguard when they have been embedded within the mise-en-scne of a mass-marketed Hollywood film? Given the directors detailed knowledge of some of the most ground-breaking contemporary movements in the visual arts (something that Jon Hallidays interviews makes clear), the inclusion of such important Modernist objects, colours and settings in a work of such heightened artifice appeared to be no simple coincidence.

Figure I.1 Charles and Ray Eames, DCW Chair, 1947.

Source: Photograph by the Eames Office, courtesy of the Herman Miller Archives

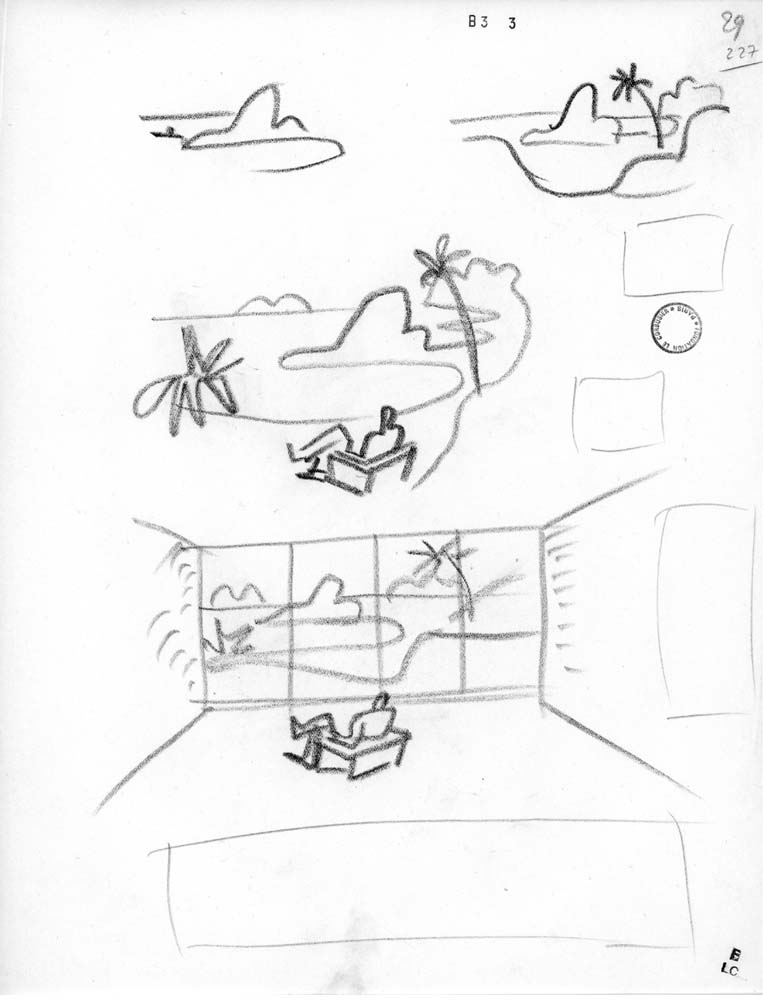

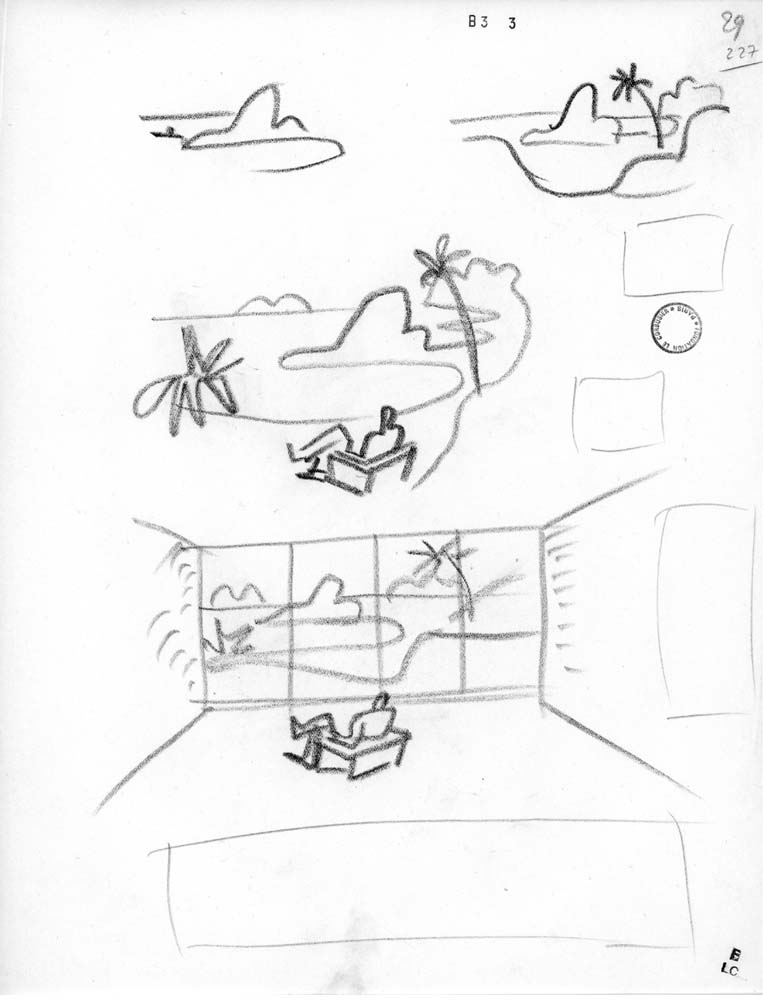

Moreover, the windows of the austere International Style hospital in which Helen Philips life-saving operation takes place also reveal the rugged hills of the New Mexico desert that surround it (the home of such pioneering American abstract artists as Georgia OKeeffe and the Transcendental Painting Group). While this moment of revelation does involve the projection of the observers thoughts and feelings onto the external topography to some degree, it also implies a reciprocal willingness to open oneself up to the transcendent experiences and unknown geographies that lie beyond the borders of the depicted space. Although the separation provided by the window frame at least partially preserves the autonomy of the pre-existing terrain, this was not meant to provoke a sense of alienation in the viewer; rather, it encourages us to reorient ourselves in relation to this condensed image of a different reality that we now perceive with an even greater clarity. After having been prompted by the architecture to reflect upon a significant aspect of the exterior landscape, the spectator is irrevocably changed by this encounter too.

Figure I.2 Le Corbusier, Original Sketch, representing a view of Rio, for the book La Maison des hommes, c.1942.

Source: Fondation Le Corbusier archives B3(3)227 FLC/DACS 2017

When they have been considered in this light, the apertures, grids, drapes, screens and vortices that are a prominent feature of Sirks mise-en-scne also often seem to offer a spiritual or intellectual template for a deeper meditation on some sort of alternative world.original viewers, Sirks melodramas have taken me on a journey to a number of destinations that I could never have imagined when I began to research this highly interdisciplinary study.

Douglas Sirk, Aesthetic Modernism and the Culture of Modernity has been based in an extensive investigation of nine of this directors most pivotal films, Final Chord (1936), Has Anyone Seen My Gal? (1951), All I Desire (1953), Magnificent Obsession (1953), All That Heaven Allows (1954), Theres Always Tomorrow (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), The Tarnished Angels (1957) and Imitation of Life (1959), though other titles will be mentioned in passing. It is divided into three parts (Sirk and the Visual Arts, The Shock of the New: Traces of Modernity and Two Architectural Case Studies), each of which contains two chapters that address interconnected themes or subject matter.

Part Two of this book addresses the psychic ambivalence that is frequently elicited by the new technologies have had such a profound impact on Western culture during the twentieth century. (