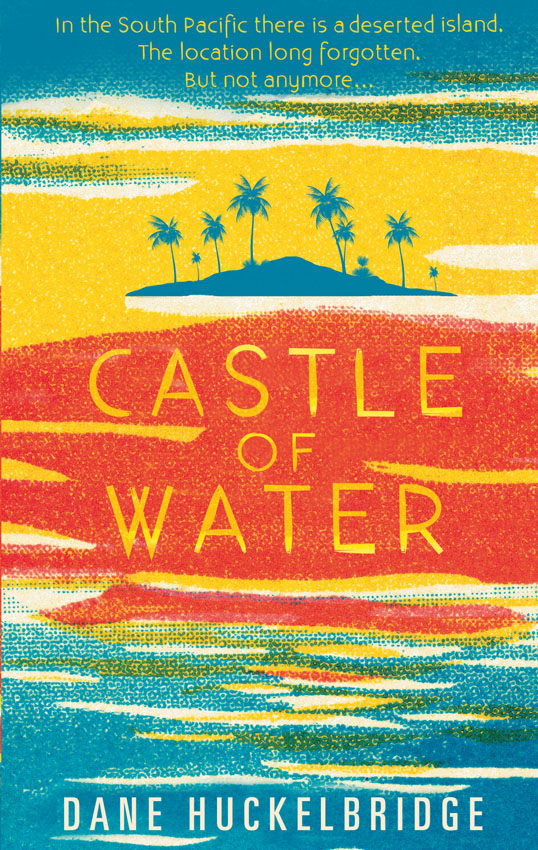

DANE HUCKELBRIDGE was born and raised in the American Middle West. He holds a degree from Princeton University, and his fiction and essays have appeared in a variety of journals, including Tin House, The New Delta Review, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic. Castle of Water is his first novel, although he has also authored two historical works on American whiskey and beer, respectively. He lives with his wife in Paris, France, and New York City.

Contrary to what bylines might have you believe, completing a novel is never a solitary affair. And this novel, in particular, owes its existence to some extremely generous and talented people. I would like to extend a heartfelt thank-you to Jim Fitzgerald for stewarding it along from start to finish, Brendan Deneen for providing crucial guidance throughout the editorial process, Nicole Sohl for tightening it up in its final stages, and Will Anderson, especially, for believing in it from the very beginning. Without their help, it would be nothing more than words in a drawer. Last, and with the utmost gratitude and humility, Id like to thank my wife, who deserves far more than a dedication or acknowledgment for the innumerable ways in which she has saved me. She is my compass and she is my home.

HQ

One Place. Many Stories

The home of bold, innovative and empowering publishing.

Follow us online

@HQStories

@HQStories

@HQStories

@HQStories

HQStories

HQStories

HQ Stories

HQ Stories

HQMusic

HQMusic

The flat is in the tenth arrondissement of Paris, on a derelict street called Chteau dEau. To find it is simple: Just take a right at the arch, go down rue Saint-Denis, steer clear of the dog shit, and you cannot miss it. To find beauty in it, however, is a bit more daunting. The charms of the alley do exist, if one squints past the worn-out tabacs and disheveled filles de joie that ply their trades along its curbs. Fortunately, the man who lives there is accustomed to squinting and proud to call the place his home.

He wakes earlier than usual on this particular morning. He does not rise immediately but lies awake for a moment, savoring the stillness of the chill blue hour. Then, at last, he decides to get up. A splash of water on the face, a quick brushing of teeth, a puckering spit, and a satisfied gargle. He smiles at his scarred and bearded reflectiongrayer, it seems, with each passing day.

Ablutions complete, its time to get dressed. First he slips on an old moth-hounded sweater, followed by corduroy trousers flecked with white paint. A Harris Tweed jacket is pulled from the closet, the elbows of which are worn down to fuzz. Oh, and shoescant forget those. The man puts on argyle socks and scuffed leather brogans and tiptoes out of his bedroom door. He considers briefly leaving a note in the kitchen but doubts hell be gone long enough to even be missed. He does, however, pause at the end of the hallway, to press his ear to another door and give it a listen. Satisfied with the silence, he leaves the flat, padding delicately down the winding stairs, past the dim halos of hall lights conferred upon wallpaper, only to realize halfway down that hes forgotten yet again to put in his contacts. Damnit. He trundles back up and plops them in without so much as a glimpse in the mirror. Then he leaves.

The man decides to have breakfast at a caf in the neighborhood, and he sits outside despite the chill. Huddled in his chair, fingers laced around his coffee, he watches the city yawn back to life. The rising sun scrubs the indigo out of the air; the streets for once smell washed and clean. Shopkeepers are slowly raising their shutters, starch-crisp waiters are unstacking their chairs. Even the femmes de la nuit have called it a night. Its all part of a timeless ritual, one of which he never tires.

The man finishes only one of his two tartines, perhaps because he is not very hungry, possibly because of something more. The untouched piece of toast is wrapped in a napkin and pocketed away for general safekeeping. He pays the waiter, slurps back the last of his coffee, and heads next door to a Turkish grocer. The door chimes and he vanishes inside, only to reemerge seconds later with a paper bag tucked under his arm. With his free hand he hails a taxi and asks to be taken to Pre Lachaise.

The driver is a friendly West African named Nol. The melodies of his homeland pulse quietly through the radio. The man likes the music and asks the driver where it is from. Senegal, the driver says. The man settles back into his seat, absorbing the rhythms and enjoying the ride. He gazes out at the fountains etched in verdigris, and the monuments steeped in history, and the streets lined with cracked cobblestones. He clutches his paper bag both tightly and tenderly, as if it is a precious thing that someone might take. He closes his eyes and lets the light bleed through his eyelids, as marimbas hint at warmer climes.

The sun is still low but fully risen when the man arrives at the gates of Pre Lachaisewhich are, incidentally, in the process of being opened by a jumpsuited groundskeeper lame in one leg. Bonjour, Claude, the man says to the groundskeeper. Bonjour, monsieur, the groundskeeper replies. Also waiting beside the entrance is a quartet of American art students, smoking cigarettes and laughing to themselves. Unlike the man with the paper bag, they are young and have been up all night. In a burst of drunken enthusiasm, they decided to pay the famous cemetery a visit.

One of the Americans thinks he recognizes the man with the paper baghe looks very familiar. The boys eyes bulge, the beard and the scars. Holy shit, he whispers, his unlit Lucky Strike tumbling from his lips. Is that who I think it is? His friends cast glances over their hunched shoulders. It is. To think, they came to see a dead rock star and instead happened upon a living legend. They titter among themselves, giddy just to be standing so close. They know he lives in Paris. And theyve certainly heard all the stories. Should they follow him in? The groundskeeper stands aside and the man with the paper bag enters. They should, and they do.

The man with the paper bag does not notice them, however. His mind is on other things. He walks with serene intent through the inordinate quietude and beauty of the place, a monument to France itself. The fading names above the crypts are soft as feathers when uttered upon the lipswhich he does, without a breath, with hardly a sound, the downy purr of double rs, the agile sweep of accents aigus.

His path takes him beneath a wicker of frosted elm trees, down a brief and chestnut-scattered embankment, to a cluster of old family plots on the cemeterys edge. He goes delicately but with purposehe knows the way, he is intimate with these surroundings. The American students trail behind by a respectful distance. They are curious but have no wish to disturb him. Wait until we tell our friends back home, they say, the insatiable lot of them murmuring as one.

The man stops at last in front of a grave, newer and less faded than the rest. The moss has yet to even stake its claim. The students hold back; they suddenly feel guilty, unintentionally intrusive. But they know they cant turn away. They look on as the object of their curiosity kneels before the grave. His head is bowed, and his hands are resting upon the headstone. He seems to be speakingbut what is he saying? They cant make out a single word. Whatever it is, it goes on for some time, until at last, his vigil concluded, the man wipes his eyes and rises to his feet. He takes something from the paper bag, something thick and clusteredwhat, theyre not certainand sets it down upon the grave. Then he turns and walks away.

@HQStories

@HQStories @HQStories

@HQStories HQStories

HQStories HQ Stories

HQ Stories HQMusic

HQMusic