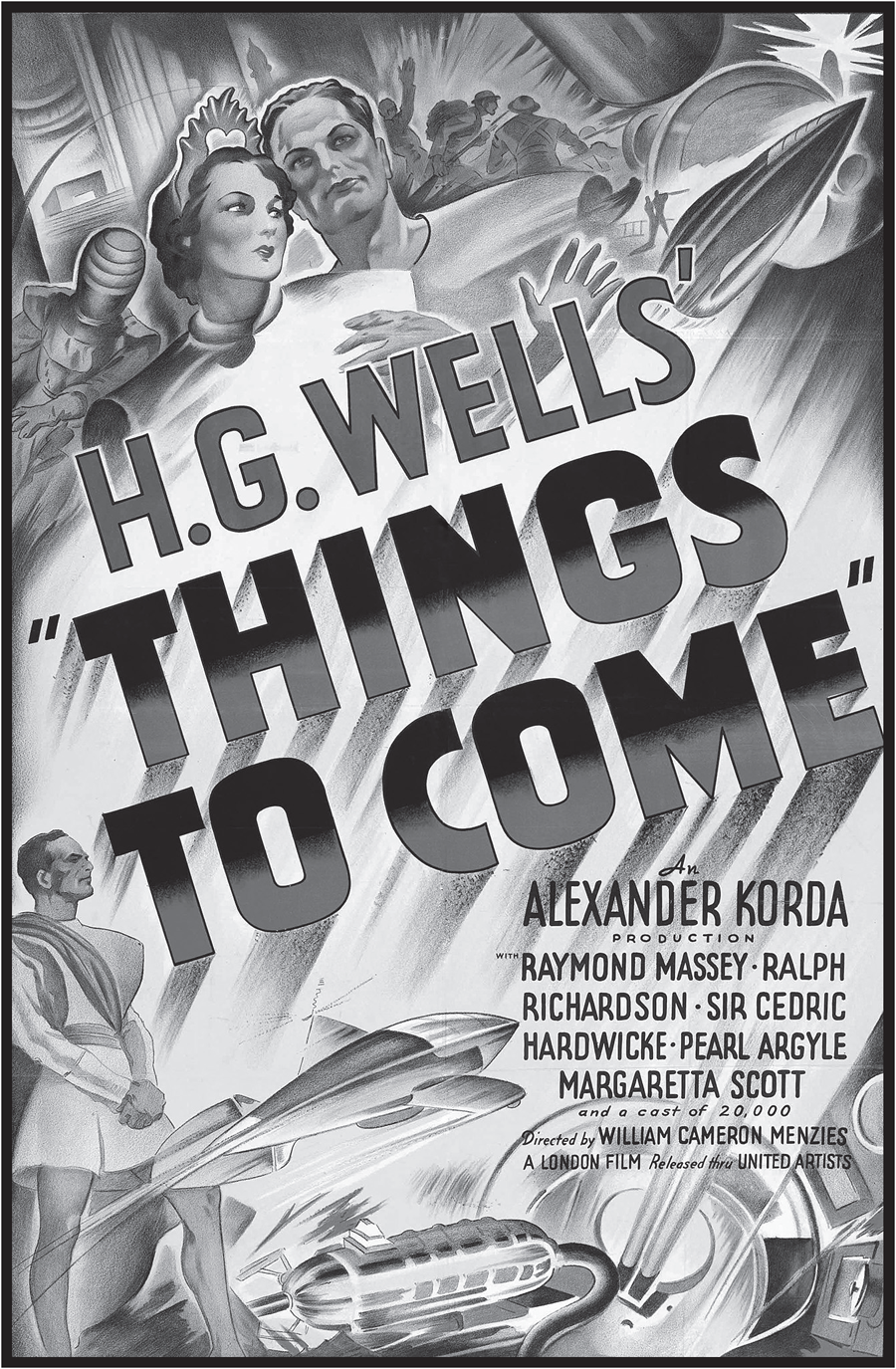

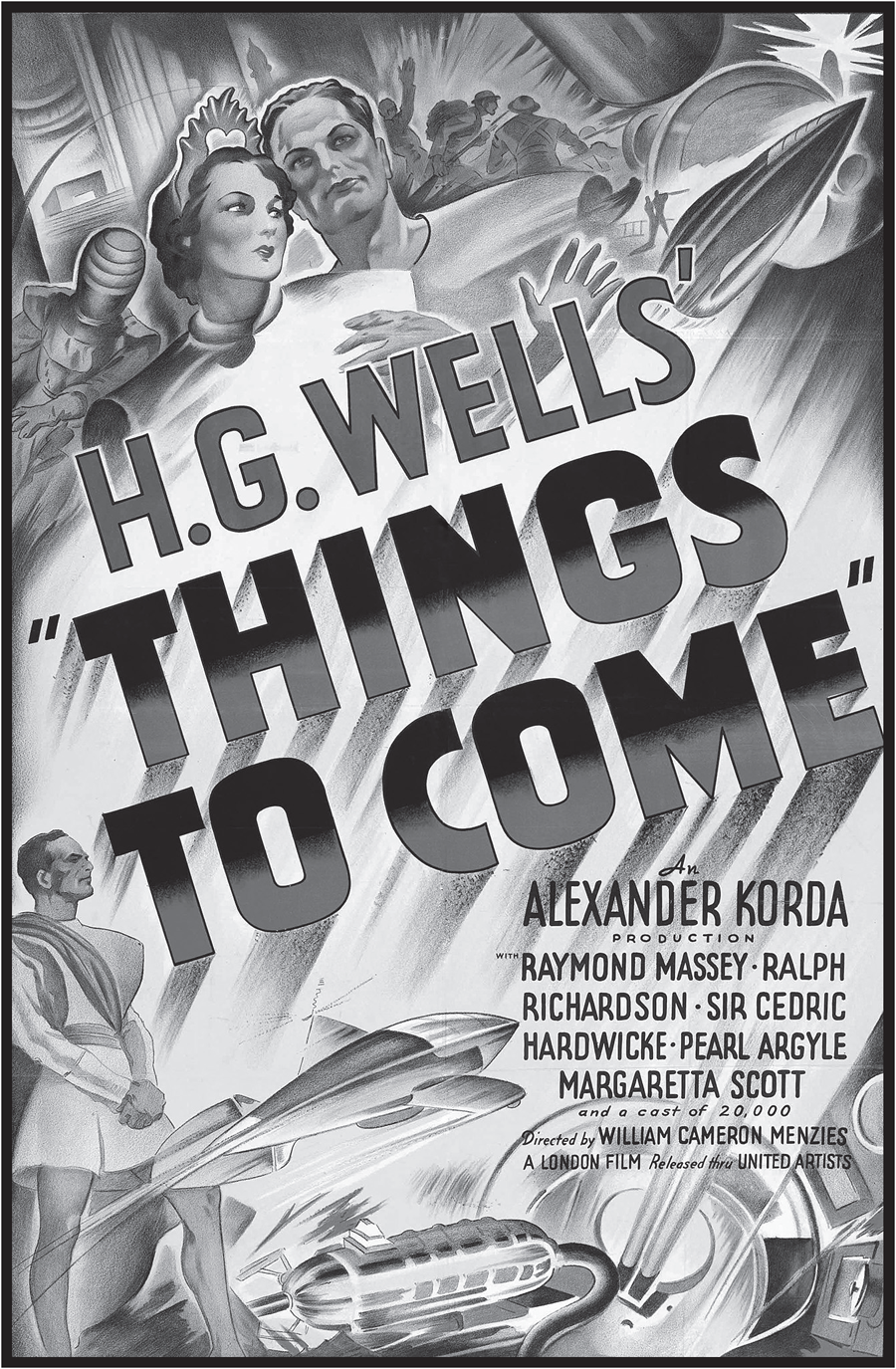

FROM FICTION TO FILM: A great many cinema classics of the sci-fi genre have been derived from important novels. William Cameron Menziess film Things to Come (1936) was adapted by H. G. Wells himself from his 1933 book, The Shape of Things to Come. Courtesy: London Films.

DOUGLAS BRODE

FANTASTIC PLANETS, FORBIDDEN ZONES, AND LOST CONTINENTS

THE 100 GREATEST SCIENCE-FICTION FILMS

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 2015 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2015

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brode, Douglas, 1943 author.

Fantastic planets, forbidden zones, and lost continents: the 100 greatest science-fiction films / Douglas Brode. First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-292-73919-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-292-73920-8 (library ebook)

ISBN 978-1-4773-0247-7 (non-library ebook)

1. Science-fiction filmsHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1995.9.S26B67 2015

791.43'615dc23

2014032144

doi:10.7560/739192

For My Three Sons: Shane, Shaun, and Shea

And my grandson, Tyler Reese

Serious science-fiction fans all!

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With great thanks to my son Shane Johnson Brode, whose contribution of time and hard work on this project brought it to fruition. Also, to my sons Shaun Lichenstein Brode and Shea Thaxter Brode, for their suggestions as to films worthy of inclusion and insights into such movies.

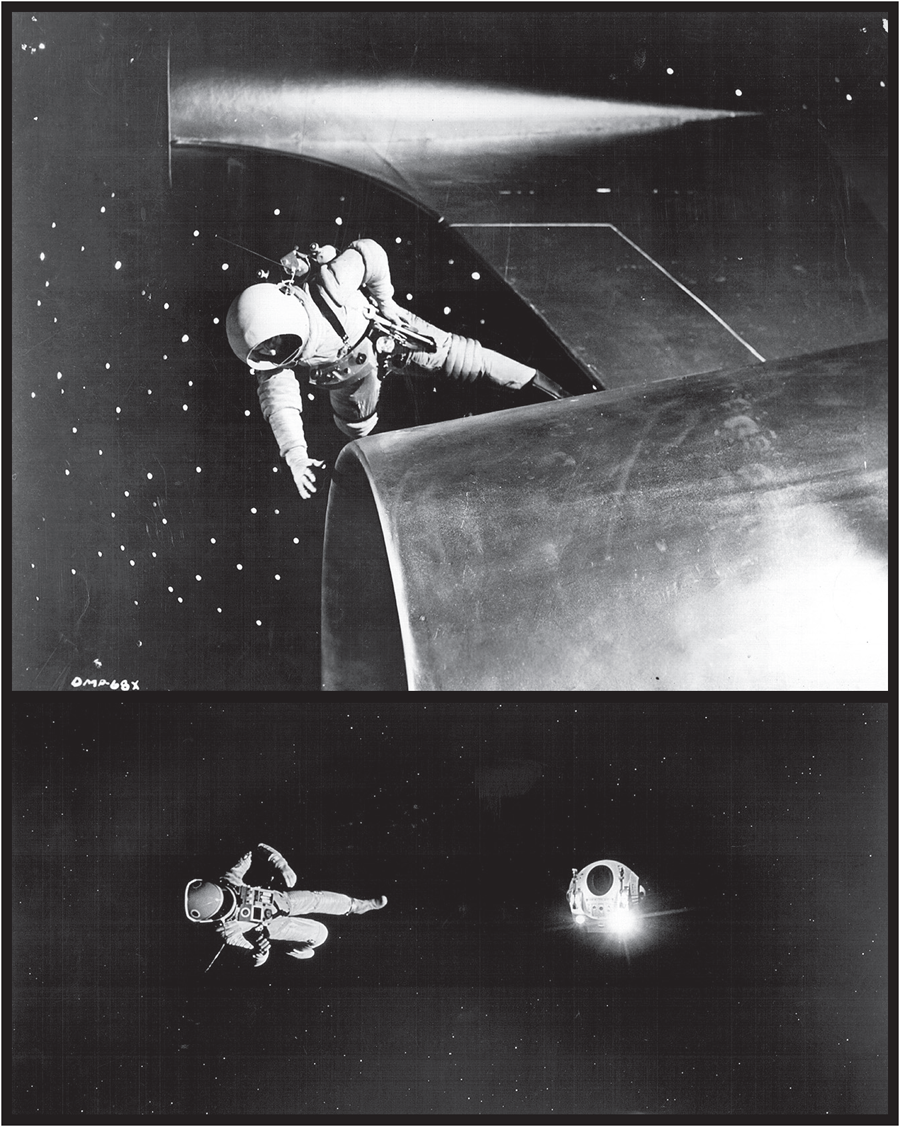

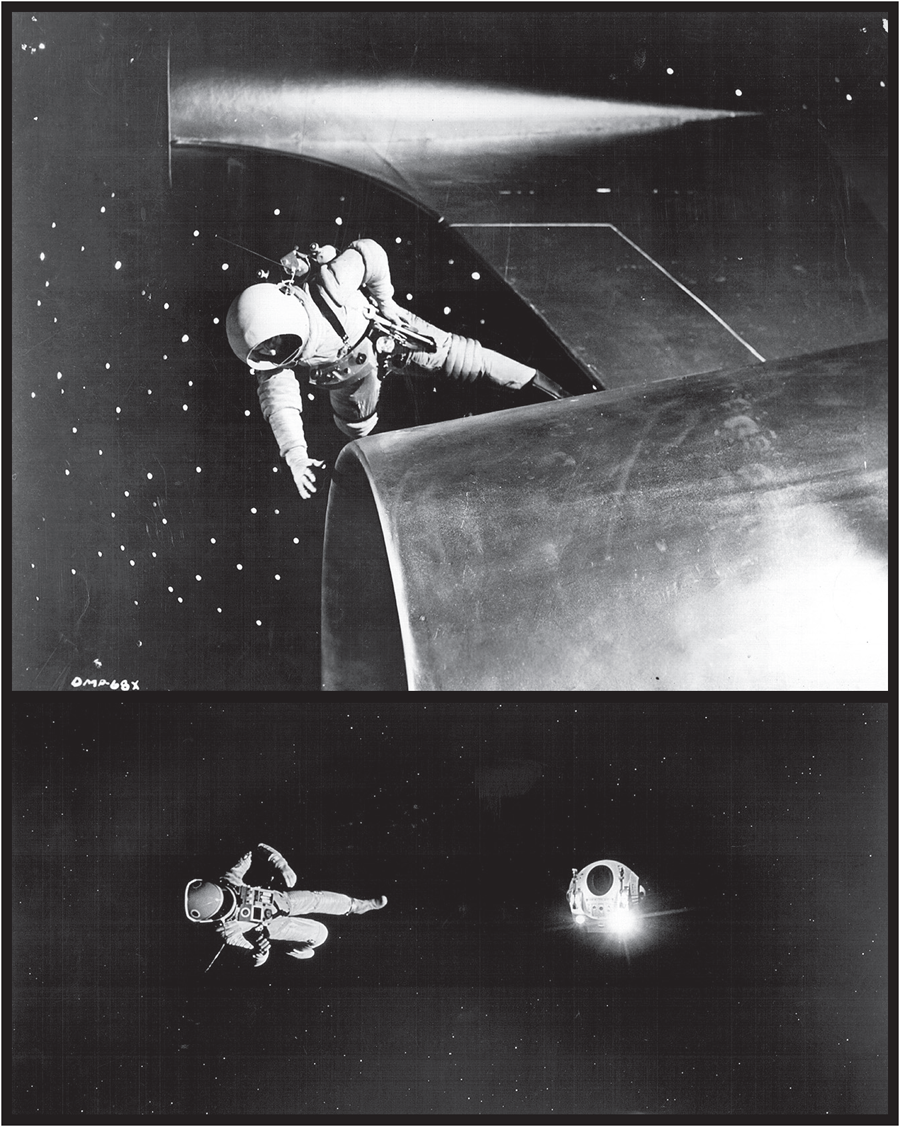

THE HIGHEST FORM OF FLATTERY: As in other genres, science-fiction filmmakers often include homages to earlier works. An ultra-realistic image of likely future travel from George Pals Conquest of Space (1955) would be almost precisely referenced in Stanley Kubricks 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Courtesy: George Pal Productions; Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

INTRODUCTION

Any attempt to pick the top 100 films in a specific genre must begin with a working definition of that unique storytelling venueor, at least, an explanation of how the term will be employed within the volume at hand. This is never as easy a process as it may initially seem. For instance, if we are hoping to choose the Ur-Western, we might well focus on The Last of the Mohicans. Yet the geography of James Fenimore Coopers 1826 novel and its many movie adaptations happens to be the East Coast. Similarly, is The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) the greatest gangster movie ever made, as many insist? Or, as others would argue, is it more appropriately considered a non-generic film about the inner workings of an American immigrant family that happens to be connected to The Family?

The genre covered here, sci-fi (or, as purists prefer to call it, science fiction), may well be the most difficult of all to summarize briefly. As Stephen King noted in his seminal book, Danse Macabre (1981), sci-fi and horror often spill over into one another, confusing the boundaries while confounding any neat definition of either. Individual works can be thought of as belonging to one of those genres or the other, depending on the angle of perception from which the piece is received. The original literary antecedent of both those types of story is Mary Shelleys Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818). Yet, that book can also considered a pre-Victorian romance, if with darker, more metaphysical aspects than other examples of this form. Diverse movie adaptations of Shelleys work have offered all three approachesmost often, one per film in order to bring the books epic length down to manageable screen time.

Ultimately, genre rules, like all rules, beg to be broken. Often, the best works of any form are the ones that go against the grain. High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), perhaps the greatest Western ever made, takes place almost entirely within confined buildings. Yet any John Ford fan knows the essence of the genre had, at least until this key juncture, been a celluloid celebration of wide-open spaces in general, Monument Valley in particular. So it goes with science fiction, space fantasy, and imaginative dramaclosely inter-related terms that mean pretty much, if not precisely, the same thing.

What seems obvious, then, becomes the first great challenge. Necessarily, Ive adopted a few rules of thumb, allowing for the necessary paring-down process.

Writing the history of the future was the earliest attempt by aficionados of a new form to put into words the essence of science fiction, created over several transitional decades between the middle of the nineteenth century and the fin de sicle by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, to name the two best-known authors. Modernist writers offered in fictional form the only valid response, at once logical and creative, to the then-evolving field of science. Previously, any such attempts to understand the human situation here on Earth or in the cosmos above, and a possible connection between the twoother than a faith-based acceptance of everything in the Judeo-Christian Biblehad been dismissed as the devils work, alchemy, paganism, or Wicca (aka, witchcraft). Almost overnight, everything changed, first in the worlds of technology and medicine, then in the popular culture that always reflects the society from which it derives.

In an early example of what Alvin Toffler a century later would refer to as future shock, a commonplace vision of how the micro- and macrocosms worked altered so swiftly that humankinds place in the universe, or at least our shared perception of it, was turned upside down. Most people could not keep up with the rapidly changing sense of who we were and, more important, why we existed. Nietzsches 1882 dictum that God is dead! couldnt have been uttered had science not called into question the legitimacy of older forms of knowledge. Nor could Einsteins theory of relativity have appeared without intellectuals wondering if indeed anything could be considered absolute. The very meaning of life in a civilization that might entirely abandon religion, while entering a brave new world of wonder and/or terror, would swiftly become an (perhaps the) issue. Fascinatingly, that would not be the case: more often than not, the genre offered a retro vision, insisting on the need to hang on to faith despite any supposed scientific evidence to the contrary.

Simply put, for a film to be about science does not necessarily imply that it will come out in favor of science. At any rate, just such a debate would come to circumscribe the twentieth century. As a result, that early way of defining (describing may be a more accurate term) the new fiction, if valuable, quickly proved to be less than comprehensive. It served well enough for From the Earth to the Moon (De la terre la lune) (1865), Jules Vernes documentary-like projection of an eventual space flight as it might likely occur, so far as the scientific data of his time suggested. However, H. G. Wellss The First Men in the Moon (1901)which included (and, to a degree, introduced) such entirely fanciful tropes as Selene, mistress of the moon, and her army of half-man, half-bug insectoidshad to be posited as another genre entirely or the opposite pole of a single genre that now required redefining.

Next page