Copper Canyon Press encourages you to calibrate your settings by using the line of characters below, which optimizes the line length and character size:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque

Please take the time to adjust the size of the text on your viewer so that the line of characters above appears on one line, if possible.

When this text appears on one line on your device, the resulting settings will most accurately reproduce the layout of the text on the page and the line length intended by the author. Viewing the title at a higher than optimal text size or on a device too small to accommodate the lines in the text will cause the reading experience to be altered considerably; single lines of some poems will be displayed as multiple lines of text. If this occurs, the turn of the line will be marked with a shallow indent.

Double-tapping on the Chinese poems will enlarge the image, if your device supports that feature.

Thank you. We hope you enjoy these poems.

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

If Chinas literary critics were put in charge of organizing a tea for their countrys greatest poets of the past, Cold Mountain would not be on many invitation lists. Yet no other poet occupies the altars of Chinas temples and shrines, where his statue often stands alongside immortals and bodhisattvas. He is equally revered in Korea and Japan. And when Jack Kerouac dedicated The Dharma Bums to him in 1958, Cold Mountain became the guardian angel of a generation of Westerners as well.

In trying to explain the reason for such high regard in the face of official disdain, I am reminded of the literary judgment of Wang An-shih (10211086).Wang was one of the most famous prime ministers in Chinese history. He was also one of his countrys greatest writers, and Cold Mountain was his favorite poet. Among the series of nineteen poems he wrote in imitation, this is number seven:

I have read ten thousand books

and plumbed the truths beneath the sky

those who know know themselves

no one trusts a fool

how rare the idle man of Tao

up there three miles high

he alone has found the source

and thinks of going nowhere else

Wang thought that a poem or essay should do more than impress and entertain us with its style. It should possess and convey some moral or spiritual value. While Wang enjoyed the elegance and erudition displayed by Chinas more established poets, he preferred the sanctuary of Cold Mountains simpler, more unpretentious poems. Unfortunately, Chinas literary judges did not share Wangs sympathetic appreciation, and Cold Mountains three hundred surviving poems did not become part of the official literary canon until nearly a thousand years after they were written.

Prime Minister Wang, however, was not alone. The great Neo-Confucian poet and philosopher Chu Hsi (11301200) was so concerned about their reprinting, he asked his Buddhist friend Abbot Chih-nan to make sure the characters were big enough for an old man to read. And so, Cold Mountains poems have been passed down to us by those who valued honesty, humor, and insight into the human condition above literary refinement.

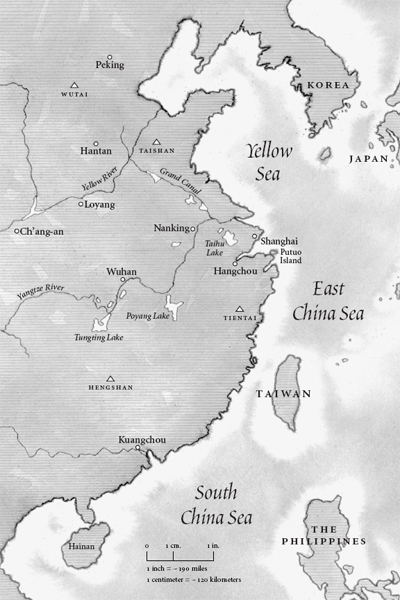

Still, despite the continued interest in his poems, Cold Mountains identity has remained a mystery. He called himself Han-shan, or Cold Mountain, after the cave he chose for his home. The cave is located in Chekiang province at the base of Hanyen, or Cold Cliff, a two-day walk from the East China Sea. Its actually more of a huge overhang than a cave. Roughly sixty meters across, thirty meters deep, and ten meters high, it faces south toward the course of the sun and the moon. Even now, Cold Mountains old home attracts few visitors. In May of 1989 and again in October of 1991, Layman Fang of Kuoching Temple arranged for a motorized rickshaw to take me and two friends there. Although it was only thirty-five kilometers, it took nearly an hour and a half to reach, such was the condition of what passed for a road.

An old farmer whose wife had died and whose children had grown up and moved away had built a roofless hut inside the cave. He invited us to share his lunch of noodles and red pepper paste, then guided us around the area. In the centuries that followed Cold Mountains disappearance, Buddhists built a monastery just beyond the base of the cliff. It had since been replaced by terraced fields of corn and peanuts, but our host told us he still dug up the occasional temple tile.

Although Cold Mountains name was linked with this remote and rocky place, he often availed himself of the hospitality of Kuoching Temple at the foot of Mount Tientai, a long days hike to the northeast. Tientai first gained attention in the third century after two herb gatherers one day hiked out of its forests two hundred years after hiking in. Not long afterward, people began moving there to cultivate the Tao and the Dharma.

Ko Hung, the most celebrated Taoist writer of the fourth century, called Tientai the perfect place for would-be immortals to carry out their alchemic and yogic transformation. Sun Cho, an equally renowned man of letters of the same era, said that Tientai represented the spiritual blossom of all mountains. And the monk Chih-yi founded the influential Tientai school of Buddhism there in the sixth century. In his will, Chih-yi asked his followers to build a temple on the site of his former hut. It was completed in 598, the year after his death, and named Tientai Temple. In 605, this was changed to Kuoching (Purifier of the Kingdom), and it soon became one of the foremost centers of Buddhist teaching and practice in all of China.

Despite Kuochings famous philosopher monks, whenever Cold Mountain visited, he preferred the company of Big Stick (Feng-kan) and Pickup (Shih-te), two men equally cloaked in obscurity. According to the few early accounts we have of him, Big Stick suddenly appeared one day riding through the temples front gate on the back of a tiger. He was over six feet tall. And unlike other monks, he didnt shave his head but let his hair hang down to his eyebrows. He took up residence in a room behind the temple library and came and went as he liked. Whenever anyone asked him about Buddhism, all he would say was, Whatever. Otherwise, he hulled rice during the day and chanted hymns at night.

One day Big Stick was walking along the trail that led between Kuoching and the nearby county seat of Tientai. Upon reaching the cinnabar-colored outcrop of rock known as Redwall, he heard someone crying. Searching in the bushes, he found a ten-year-old boy. The boy said he had been left there by his parents, so Big Stick picked him up and brought him back to Kuoching. The monks tried to locate his parents, but no one came forward to claim him. So Pickup, as Big Stick called him, stayed at the temple and was placed under the care of Ling-yi, the chief custodian, who put the boy to work in the main shrine hall.

One day while he was dusting the statues, Pickup went up to the altar and ate a piece of fruit left by a worshiper in front of the statue of Shakyamuni. Then in front of the statue of Kaundinya, the Buddhas first disciple, he yelled, Hinayana monk! The other monks who saw this reported it to Ling-yi. The chief custodian chided the monks for their lack of forbearance but agreed to put Pickup to work in the kitchen, instead, where it seems he spent the remainder of his years at the temple. This was where Cold Mountain met him. And the two became such close friends, their images are still used by Chinese in their homes to represent marital harmony.