Table of Contents

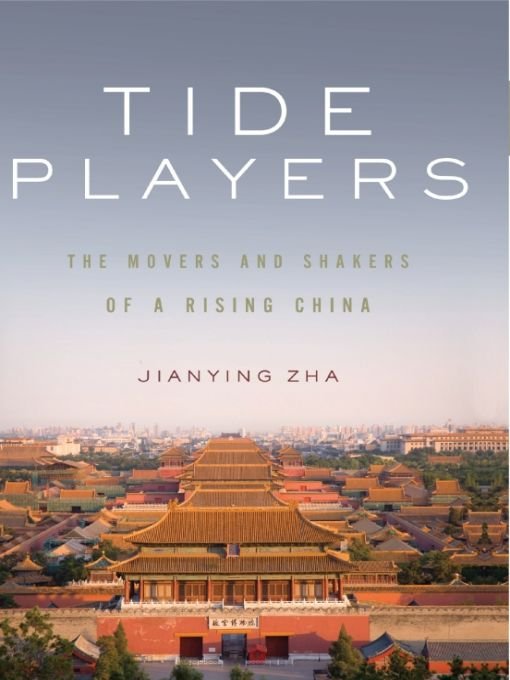

ALSO BY JIANYING ZHA

IN ENGLISH:

China Pop: How Soap Operas, Tabloids, and Bestsellers Are Transforming a Culture

IN CHINESE:

(The Eighties)

(Speak East, Talk West)

(River Frozen Under the Jungle)

, (To America, to America !)

To Siri

Tide players surf the currents,

The red flags they hold up do not even get wet.

,

Pan Lang (?-1009), Jiu Quan Zi ()

There is a tide in the affairs of men.

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

As life is action and passion, it is required of a man that he should share the passion and action of his time at peril of being judged not to have lived.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Memorial Day Address (1884)

Introduction

Explaining China to Americans has always been a tricky business for me. Born and raised in Beijing, I have ended up, to my complete surprise, living between the United States and China for most of my adult life. But I will never forget the very first questions I had to answer about China, in 1981.

I had just arrived in Columbia, South Carolina. I was twenty-one, I had never been on an airplane before, and I spoke bad, broken English. China had started its reform and open-door policies, but there were not yet many Chinese students in the United States. And no TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) yet in China. So it was a small miracle that I, a student in the Chinese Department of Peking University, actually obtained a scholarship to study in the English Department of the University of South Carolina. Only much later did I realize that this was due largely to the fact that the English Department of USC had never in its history received an application from mainland Chinameaning not Taiwan, not Hong Kong, but Big Red China! Evidently the curiosity and the temptation of offering this brave young applicant an opportunity was simply too great to resist. And I remember how much Dr. Ross Roy, chairman of the English department, enjoyed walking me around the campus and introducing me to absolutely everyone we ran into: This is Miss Zha, he would start, pausing dramatically before dropping the bomb, She is from Beijing, China!

It was in those first bewildering, exciting days of my new American life that Larry Bagwell, a fellow English Department student and a charming, bighearted, tall Southern boy who became my first American buddy, started asking me to explain China. It was a beautiful autumn afternoon, and we were sitting on the lawn drinking Coke after class. Jane, Larry said, using the new American name he had given me, at my request, to overcome the impossibility of being called Jianying, is it true the Chinese eat fried grasshoppers dipped in chocolate sauce as a delicacy?

What? I blinked, almost choking on my Coke. I knew the word chocolate, but grasshoppers?

If this was half pulling my leg, then Larrys next questions were certainly more serious: Does China have TV shows, you know, like soaps and sitcoms? Actually, do Chinese have home television? Before I could answer, he added apologetically, We just dont know anything about China, you see, and some folks here think yall dont even have electricity out there!

This conversation is carved into my memory as a moment of great relief. I realized that I was not the only one so clueless about another big countryabout another people and their culture. And it didnt matter that I thought soaps referred to a stack of cleaning squares. I knew what electricity and chocolate meant in English, which was a darn good start! I knew I would be fine in America.

What I didnt know then, of course, was how much and how fast my homeland would change! Nor could I predict that, merely fourteen years after Larry so casually tossed the bizarre, alien word soaps to me, I would myself write a book in English and publish it in America under the title China Pop: How Soap Operas, Tabloids, and Bestsellers Are Transforming a Culture.

In 2008, Larry finally made it to the grasshopper country. He and his daughter boarded that long transatlantic flight and did China. He sent me breathless letters about their bike trip through the Zhejiang countryside, the epiphany they experienced inside the meditation cave of the Tang monk poet Han Shan, the crazy shopping they did in Shanghai. We are having a swell time here, Larry wrote, and the Chinese we meet everywhere have been wonderful to us: your folks are such a warm and generous people. I was delighted, and wrote back, I never had the opportunity to reciprocate your hospitality to me back then, but it looks like my folks are helping me to repay some of that old debt.

I belong to the generation of Chinese who grew up during the Cultural Revolution. My childhood was punctuated with memorable events such as the terrifying night ransacking of our home, witnessing neighbors being beaten to death or jumping to their deaths from the rooftop, my fathers years of absence and receiving monthly letters from the labor camp, attending schools with daily political lectures and few books to read. I finished high school in 1977, and even though Mao Zedong had died the previous year and the Cultural Revolution had ended, we were still sent to do farmwork in a village outside Beijing. Everything was in flux as the Communist Party leadership scrambled to reverse Maos policies and put the country on a different track, including reinstating the university entrance exam, which had been suspended for over a decade. That autumn I made a trip back to the city to take the exam, and, months later, as I was plowing the field with villagers, the news came that I was accepted into Peking University!

I will never forget spring 1978, my first euphoric days at Beida, as Peking University is called. At eighteen, I was the youngest in my class, but many of my older classmates had spent a decade or more in factories or on farms. None of us had dreamt of this daystudying at Chinas number-one university! To the individuals who remember the Red Guard and those who became the first beneficiaries of reformdisillusioned yet idealisticthe class of 1977 became a symbol and a legend in China. It was a generation burned by radical politics and loss of youth, yet fired up with a sense of mission for the countrys future. Many from that class have moved on to leadership positions in politics, business, academia, culture, and media. Many are near the apex of their careers and influence. They form an elite part of the new establishment in todays China.

I have taken a slightly different path from that of my peers. My Beida classmates considered me a bit insane for going to South Carolinathe Guizhou of America, as one of them put itand missing out on the fabulous job offers waiting on our graduation day. But, whether it was a genetic connection to my grandfather, who had left his Hubei hometown in the early part of the last century to study in France, or just a wild curiosity about the outside world and a crazy thirst for adventure, I just had to leave. South Carolina proved to be an enchanting, idyllic first chapter of my American education; it was there that I discovered the charms of Flannery OConnor and Elvis Presley, camping trips in the Smoky Mountains with guitar and marijuana, and horseback riding on a Southern farm. After transferring to Columbia University, I fell in love with New York, the city that would become my second home. By 1986, however, just as I was growing restless and ambivalent about the prospect of becoming an academic professional, I began to hear the calls from my homeland. Chinese visitors to New York and excited letters from my Beida classmates described a scene of great cultural and intellectual ferment; barriers were being broken down and new ideas and experiments were being put to the test. China sounded like a romantic place buoyed on bright hopes and full of possibilities. I had always wanted to be a writer and to be involved with my countrys change and progress. So in 1987, right after passing my doctoral orals, I left for China.