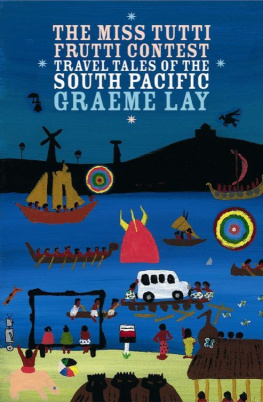

In memory of my father Donald Luigi Lay (191497) who served with the New Zealand Army in the South Pacific in World War Two

INTRODUCTION

COUNTLESS THOUSANDS of international travellers have seen the Pacific through the windows of a jet liner cruising at 11,000 metres. Far fewer have seen it at sea level, or visited some of the scores of high islands and atolls which are strewn across Earths largest ocean like constellations in a watery universe. Just to fly over this universe is to miss a great deal, for each of the inhabited islands of the Pacific is a miniature world, with its own distinctive culture and way of life. The Miss Tutti Frutti Contest is about my exploration of some of these island worlds and my encounters with some of their inhabitants.

My fascination with islands began long before I ever went to one. As a boy growing up in a small town on the rocky, windswept Taranaki coast, the sea became an intimate part of my life. Rock-pool exploration, fishing, swimming, surfing: all these activities brought me into close contact with the sea. And as an avid reader from early boyhood, the books I read sea adventure stories, mainly reflected this intimacy. If the story was set on an island, I found it irresistible. I remember in particular reading and re-reading my fathers copy of The Coral Island, by R. M. Ballantyne, along with Robert Louis Stevensons Treasure Island and Enid Blytons Five on a Treasure Island. In my imagination, islands were places of romance and adventure, exotic locations with infinite possibilities.

When I first visited the islands of the South Pacific as an adult twenty years ago, I was in no way disappointed by what I found there. The islands shores, reefs, lagoons and forests captivated me. From their coasts or mountains the Pacific Oceans beauty and changing moods could be readily observed: silken and docile one day, tempestuous and threatening the next. And every day, spellbinding.

Added to these natural attractions were the people I encountered, the locals as well as the often bizarre outsiders who had made the Pacific their adopted home. The indigenous cultures reached back into the sea mists of prehistory. There were languages which had been spoken for thousands of years, songs, dances and art which traced their history, and whose appeal was alluring. Superimposed on these traditional cultures was the introduced way of life of the Europeans and Asians men mainly who had come to the South Pacific for a variety of reasons, some honourable, some not. The subsequent blending of these cultures and peoples has produced something unique and special in the islands of the South Pacific.

The stories in this book are the collected accounts of many separate journeys taken over the last decade, at times conflated to iron out the creases. They are intended primarily to entertain, but if readers become informed as well, that will be gratifying. The collection confines itself to the islands of tropical Polynesia rather than the other great Pacific cultural spheres of Melanesia and Micronesia because it is in Polynesia that this writers interest lies. It is not intended to be a guidebook; there are many of those already available. Instead, it tries to convey some of the enchantment and surprise I have found when visiting the islands of the South Pacific islands best savoured not from high in the air, but with feet firmly on the ground or dipped in the warm ocean waters.

GRAEME LAY

May 2004

ONE

ME AND MY TUMUNU

NGAPUTORU, COOK ISLANDS

IN COOK ISLANDS MAORI theyre called Ngaputoru, the Three Roots. Atiu, Mitiaro and Mauke are a trio of raised, flat-topped coral atolls, forty minutes by air north-east of Rarotonga. For years theyve teased my curiosity whenever Ive spied them on a map; now at last Im on my way to see them.

Its hard to stay aloof from your fellow passengers when there are eighteen of you in a twenty-seater plane. The seating configuration lends itself to instant intimacy. Right alongside me are a German couple in their late twenties. He is small and compact, with black hair already flecked with grey; she has short brown hair, green eyes, moulded cheekbones and a permanently wide-eyed expression. Both have tanned, olive skin. Jurgen and Helga are thoroughly natty. Their clothing is chic-casual; they look like models from some deluxe department store in their home city of Cologne. Helga carries a video camera which she claps to her right eye socket and points at the mountains of Rarotonga as we soar from the islands runway. Then they laugh and chatter excitedly for a time, before Jurgen puts his head on her shoulder and dozes off.

Behind me is an Australian family of four: Deidre and Gavin and their two small boys, Troy and Zane. Troy, who at six is the elder by a year, is the strong, silent type; Zane speaks for both boys, loudly: Hey! Wow! Look! The propellers goin fast! Look, Mum, look at how eets goin. Hey, Dad! Were mooveen, were mooven!

Gavins short and stocky, with long, crinkly blond hair and a flushed face. He wears a red T-shirt that proclaims that Tooheys is Simply The Best. Deidre turns to me and introduces herself. Shes small and clear-skinned and must have been pretty once, but now shes hollow-chested and her long brown hairs gone dead at the ends. They run a pub in upstate Victoria. No wonder Deidre looks tired: it must be hard being a publicans wife in Wobbadonga. Theyve come to the Cook Islands, Gavin explains, to make a complete break and to show the boys the sea. Weve got another one at home, says Deidre, looking even wearier at the thought. Three months old. Hes staying with Gavins folks. She sighs philosophically, wipes Zanes streaming nose, gives me a rueful smile. Three boys under seven

As I stare through the windshield between the two Air Rarotonga pilots, a level, green, reef-ringed island comes into sight. Mitiaro. The plane begins to descend, swaying and dipping towards a white crushed-coral runway.

Neither I nor the Aussie family are getting off here were on our way to Atiu but Jurgen and Helga are. The plane taxis towards the terminal, a blue and yellow fibrolite shed in front of a tall stand of coconut palms. As it comes to a shuddering halt, we can see that something important is happening.

The front porch of the shed is crammed with people. Six very fat, barefoot women are leaping, singing and wriggling their hips to the accompaniment of another two women who are thumping bass drums. Helga points her video camera at the window and presses the trigger.

The plane door opens and we disembark. The crowd in the terminal rushes towards us. They are almost all women, all large, all singing at the tops of their voices and wriggling their hips in a none too subtle mime. They are covered in thick garlands of fern, flowers and pandanus leaves. Two of the women, who are so festooned with foliage they look like matching Christmas trees, come aboard the plane. They are weeping the party is evidently their farewell.

Theres no apparent sadness on the part of the others, though. They simply redirect their emotions towards the German couple, who are quickly surrounded by the shouting, cackling band. The drums are thumped even more vigorously as Jurgen and Helga are borne away to the rear of the terminal building and a rusting Bedford truck which looks as if it should be an exhibit in a transport museum. The Germans Gucci luggage is tossed aboard and pandanus leis are thrust over their heads as theyre bundled on to the tray of the truck.

The rest of us are now back on the plane, watching the welcoming show through the windows. Jurgen and Helga are completely engulfed; we can just see their two faces, fixed in a rictus of astonishment and apprehension, as the truck moves off along a dusty road.