Praise for W. David Marxs Ametora

This is what happens when a really smart person takes on a really interesting topic. Japanese culture and fashion come shining into view.

Grant McCracken, anthropologist and author of Culturematic and Chief Culture Officer

W. David Marxs Ametora answers the questions I had about the history and direction of menswear in Japan, and his research and analysis will undoubtedly be the authoritative word on the subject for years to come. This is a marvelously written, important, and necessary read for any student of global fashion today.

G. Bruce Boyer, author of True Style

W. David Marxs Ametora is a careful, complex, wildly entertaining cultural history of the highest caliber. This book will obviously be of immediate and considerable appeal to Japanophiles, classic-haberdashery connoisseurs, and other assorted fops, but its true and enormous audience ought to be anyone interested in the great hidden mechanisms of international exchange. In an age overrun with hasty jeremiads about the proliferation of global monoculture, Marx has given us quite a lot to reconsider. Ametora is a real pleasure.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus, author of A Sense of Direction

Ametora is a reflection of its authors own unique place in contemporary Japanese culture. W. David Marx is an astute writer, historian, and critic of Japanese culture and its relationship to the global youth culture. Marxs book explores the often hidden connection between Tokyo and American style that has eluded many writers before him. Less about runways, more about the urban street, this is an important documentation of the reinvention of American style.

John C. Jay, president of Global Creative of Fast Retailing

Ametora cuts through the myth, postulation, and hearsay that have long plagued the Japanese fashion origin story. David Marx has crafted the first thoroughly researched and well-written narrative that explains how Japan became the unlikely vanguards of American clothing styles. A must-read for anyone with even a passing interest in mens fashion, cultural assimilation, or otaku obsessionsAmetora is basically the bible of Japanese menswear.

David Shuck, managing editor, Rawr Denim

Copyright 2015 by W. David Marx

Published by Basic Books

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Cover Credits:

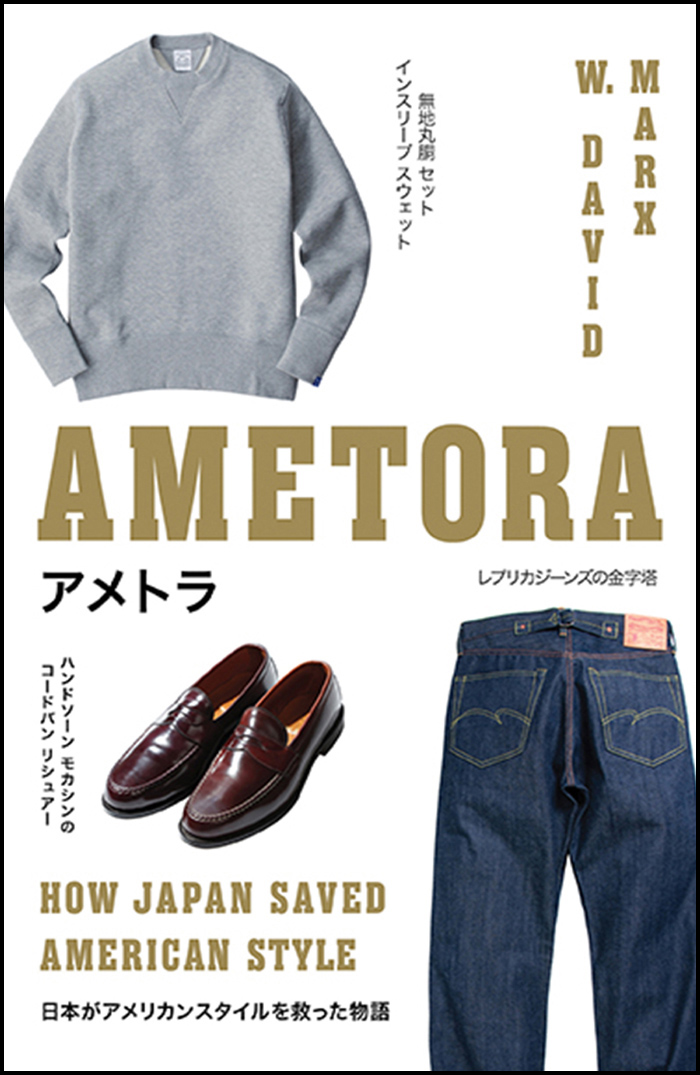

Gray crewneck sweatshirt from Loopwheeler, made from slow-moving, vintage Tsuriamiki knitting machines discontinued from mass production in the mid-1960s. (Image courtesy of Loopwheeler)

Jeans are Studio Dartisans DO-1 model, first made in 1986. The DO-1 kicked off the vintage reproduction boom in Japan. (Image courtesy of Studio Dartisan).

A pair of Leisure Handsewn shell cordovan loafers made in Massachusetts by American brand Alden, special ordered for Japanese retailer Beams+. (Image courtesy of Beams)

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944908

ISBN: 9780-465-07387-0 (eBook)

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents

Morris and Sally

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

IN THE SUMMER OF 1964, TOKYO PREPARED TO HOST THOUSANDS of foreign guests for the Olympic Games. Planners hoped to reveal a futuristic city reborn from the ashes of World War II, complete with sprawling highways, modernist stadium complexes, and elegant Western restaurants. As old-fashioned trolley cars disappeared from the streets, a sleek monorail debuted to whisk tourists into the city from Haneda Airport.

The Tokyo government paid special attention to Ginza, the crown jewel of the city, knowing that tourists would gravitate towards its luxury department stores and posh cafs. Ginzas community leaders eliminated any possible suggestion of postwar poverty, even replacing wooden garbage cans with modern plastic ones.

These cleanup efforts proceeded steadily until August, when the switchboards at Tsukiji Police Station began lighting up with frantic phone calls. Ginza shop owners reported an infestation on the main promenade, Miyuki-d

ri, requiring immediate assistance from law enforcement: There were hundreds of Japanese teenagers hanging around in strange clothing!

ri, requiring immediate assistance from law enforcement: There were hundreds of Japanese teenagers hanging around in strange clothing!

Police sent reconnaissance teams to the scene, where they discovered young men wearing shirts made from thick wrinkled cloth with unusual buttons holding down the collar, suit jackets with a superfluous third button high up on the chest, loud madras and tartan plaids, shrunken chino pants or shorts with strange straps on the back, long black knee-high socks, and leather shoes with intricate broguing. The teens parted their hair in a precise seven-to-three ratioa look requiring the use of electric hair dryers. Police soon learned that this style was called aibii, from the English word Ivy.

Throughout the summer, tabloid magazines editorialized against these wayward teens in Ginza, dubbing them the Miyuki Tribe (miyuki-zoku). Instead of dutifully studying at home, they loitered all day in front of shops, chatted up members of the opposite sex, and squandered their fathers hard-earned money at Ginzas menswear shops. Their pitiful parents likely had no idea about their tribal identities: the teens would sneak out of their houses dressed in proper school uniforms and then slip inside caf bathrooms to change into the forbidden ensembles. The press began to call Miyuki-d

ri, a street name that honored the Emperors departure from his palace, Oyafuk

ri, a street name that honored the Emperors departure from his palace, Oyafuk

-d

-d

ristreet of unfilial children.

ristreet of unfilial children.

The media condemned the Miyuki Tribe not just for their apparent juvenile delinquency, but for sticking a dagger right into the heart of the national Olympic project. The 1964 Summer Games would be Japans first moment in the global spotlight since their defeat in World War II, and would symbolize the countrys full return to the international community. Japan wanted foreign visitors to get firsthand views of the countrys miraculous progress in reconstructionnot disobedient teens clogging up the streets. Japanese authorities feared that American businessmen and European diplomats sauntering over to tea at the Imperial Hotel would run into an ugly spectacle of wicked teenagers in frivolous shirts with button-down collars.