THE COMFORT OF THINGS

THE COMFORT OF THINGS

DANIEL MILLER

polity

Copyright Daniel Miller 2008

The right of Daniel Miller to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2008 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK.

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-5536-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10.75 on 14 pt Adobe Janson

by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

To Rickie, Rachel and David

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

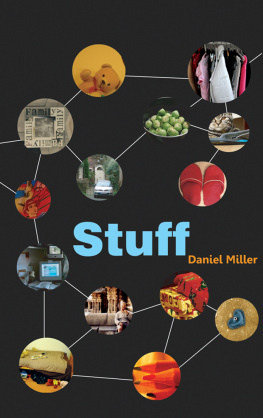

My rst acknowledgement has to be to my co-researcher, Fiona Parrott. All the material on which this book is based derives from research carried out in direct collaboration with her. The success of the project came in large measure from the effective rapport we developed in our eldwork. We also discussed the interpretation of each household during our eldwork, which no doubt has informed my writing about them. This book would simply not have been possible, or would at least be a great deal poorer, without the quality of her contribution. But in turn I am sure we would both wish to thank the many, many people who gave to us the considerable gift of their time and patience in order to help with our research. We hope that, eventually, they have not regretted that they did not do the obvious London thing and slam the door on us, and that we were not too tiresome. I hope that through this and subsequent publications they will feel that their stories have contributed to something worthwhile. I also acknowledge the considerable amount of time and effort that my wife, Rickie Burman, gave towards helping me with the manuscript. I would like to thank the following for comments on an earlier draft: Mukulika Banerjee, Barbara Bender, Haidy Geismar, Martin Holbraad, Rachel Miller, Marjorie Murray, Anna Pertierra and Michael Rowlands. I am grateful to John Thompson and Polity for taking on this project. Finally my thanks go to Olga Neva for designing the book cover and for including our cat.

PROLOGUE

This book is the story of thirty people, almost all from a single street in South London. They are selected from one hundred individuals and households studied over seventeen months by myself and Fiona Parrott, a PhD student in my discipline of Anthropology. It is also a book about how people express themselves through their possessions, and what these tell us about their lives. It explores the role of objects in our relationships, both to each other and to ourselves. We live today in a world of ever more stuff what sometimes seems a deluge of goods and shopping. We tend to assume that this has two results: that we are more supercial, and that we are more materialistic, our relationships to things coming at the expense of our relationships to people. We make such assumptions, we speak in clichs, but we have rarely tried to put these assumptions to the test. By the time you nish this book you will discover that, in many ways, the opposite is true; that possessions often remain profound and usually the closer our relationships are with objects, the closer our relationships are with people. This is why the rst two portraits are called Empty and Full.

The diversity of contemporary London is extraordinary, and begs to be better understood. But, increasingly, peoples lives take place behind the closed doors of private houses. How can we gain an insight into what those lives are like today: peoples feelings, frustrations, aspirations, tragedies and delights? Not television characters, not celebrities, but real people. How could one ever come to know such things about perfect strangers? We could try and knock on doors and ask to talk with them, to hear their stories. If you can persuade them you are not selling anything, not Jehovahs Witnesses, they might let you in they did let us in. But asking people about themselves is by no means straightforward. English people, in particular, often seem embarrassed by direct questions about their intimate lives and relationships. Sometimes people from other countries embarrass us in turn, by gushing forth these detailed accounts of their lives. Yet often you feel you are listening to a script; something readily prepared for such an encounter. They sound as much a justication or self-therapy as an account. Language is often defensive, restricted and carefully constructed as narrative. You can ask people about themselves, but the results are often much less informative than one would like.

This book takes you on a different route towards this goal. The questions were not only put directly to the people who opened their doors. We also put our questions to the interior of the house. We asked what decorations hung on the walls, what the people who greeted us were wearing, what we were asked to sit on, what style of bathroom we peed in, whose photographs were on display, what collections were arrayed on mantelpieces. This might seem a rather absurd thing to do. How can one ask questions of things that cannot speak for themselves?

Objects surely dont talk. Or do they? The person in that living-room gives an account of themselves by responding to questions. But every object in that room is equally a form by which they have chosen to express themselves. They put up ornaments; they laid down carpets. They selected furnishing and got dressed that morning. Some things may be gifts or objects retained from the past, but they have decided to live with them, to place them in lines or higgledy-piggledy; they made the room minimalist or crammed to the gills. These things are not a random collection. They have been gradually accumulated as an expression of that person or household. Surely if we can learn to listen to these things we have access to an authentic other voice. Yes, also contrived, but in a differ ent way from that of language. I dont pretend to be Sherlock Holmes or Poirot, let alone CSI sleuthing for clues to solve a puzzle. The detectives and forensics tend to look at the inadvertent, while in this book I feel I am paying proper respect to that which some people have themselves crafted as patiently as any artist, as an outward expression of themselves. The original painters of these portraits are the people who appear in this book.

And what pictures they painted. Our only hypothesis in starting this work was that we had no idea what we would nd on this entirely ordinary-looking street. This proved correct. Could I have imagined that one morning we would meet a man who was responsible for the death of dozens of innocent people, and, on the very same afternoon, a woman who had fostered dozens of the most deprived children of the area? I didnt expect to participate in the most charmed Christmas since Fanny and Alexander, or to hear how a CD collection helped someone overcome heroin. I didnt know you could nd vintage Fisher Price toys on eBay or expect to hear such a convincing paean to the wonderful world of McDonalds Happy Meals. I had no reason to see a logical connection between a laptop and the customs of Australian Aboriginals. I hadnt thought of Estonia as an outer London suburb, or understood the potential of tattoos for controlling memory. I had no reason to expect this ordinary London street to include such sexual exhibitionism, or the tyranny of Feng Shui. I didnt know one could care for a dog with quite such tenderness, or really nd life starting at sixty. I hadnt registered quite how devastating divorce can be for children; I had underestimated the vast range of objects that people collect and why exactly they collect them. I wouldnt have guessed that teaching sociology might t well with wrestling, or anticipated that image of goats looking amazed at basketball champions. I hadnt predicted that I would get such an opportunity to share my affection for John Peel, or learn about prostitutes and custard. Above all, I sort of expected, but couldnt really fully imagine, the sadness of lives and the comfort of things.

Next page