Contents

Guide

Pages

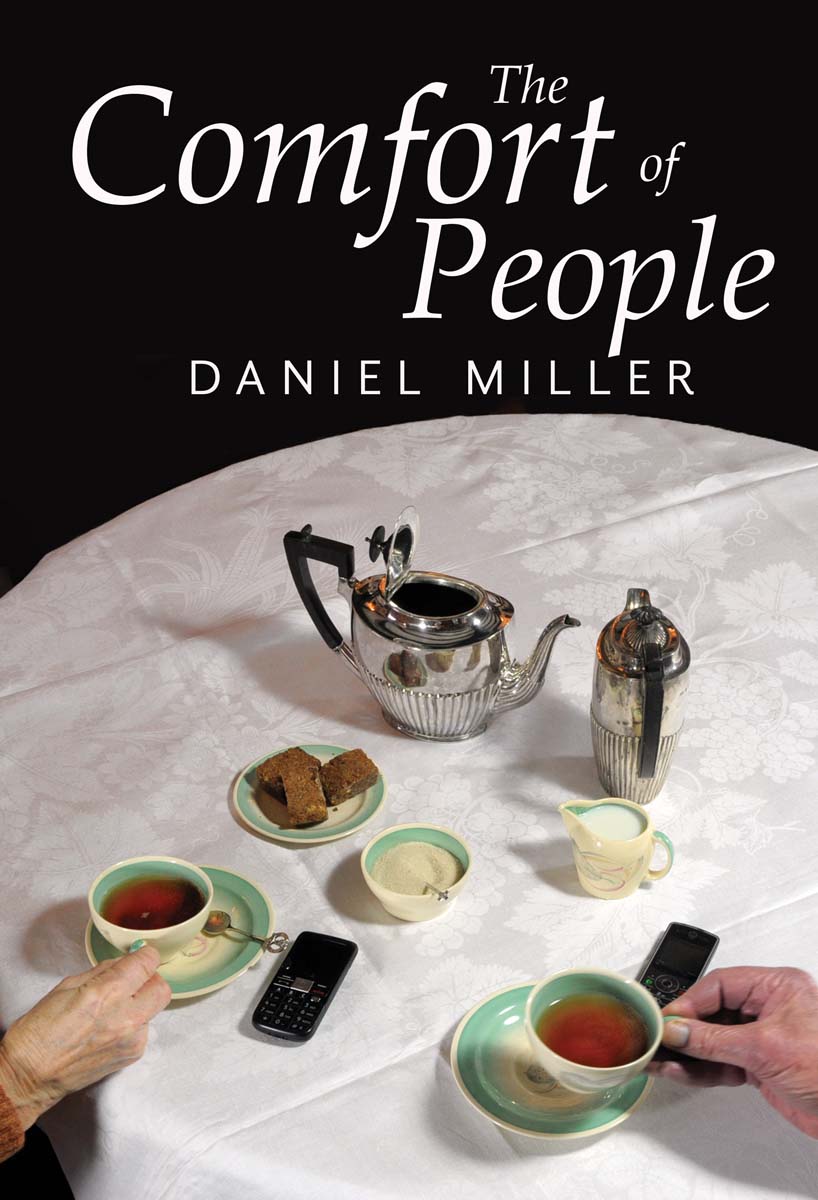

The Comfort of People

Daniel Miller

polity

Copyright Daniel Miller 2017

The right of Daniel Miller to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2017 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing, Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2435-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the anonymous informants for this study, especially those terminal patients who agreed to give their precious time to these discussions. I am indebted to Maria, who jointly conducted with me all the hospice interviews and who commented on this manuscript. Also thanks to Dr Helena who, much to my surprise, since I considered myself quite unsuited to the task, suggested that I should conduct research with hospice patients. Also thanks to the various nurses, here generalized as Justine. I am also very grateful to Dr Ros Taylor MBE, Clinical Director of Hospice UK, who agreed to write a foreword to the volume.

I would like to thank Amelia Hassoun and Sabrina Miller who worked as interns, and especially Ciara Green, my co-researcher on the village ethnographic study who also undertook much of the transcribing of these interviews. I am grateful to those who have read the manuscript and made editorial comments: Amelia Hassoun, Rickie Burman, Laura Haapio-Kirk and Xinyuan Wang. The project forms one part of the Why We Post project and I am grateful for the support of the whole team and the funding from the European Research Council grant ERC-2011-AdG-295486 Socnet. Parts of the conclusion have been previously published as The Tragic Dnouement of English Sociality, Cultural Anthropology 30(2): 33657.

Foreword

I have learnt over the years, as a hospice physician that, as life ebbs, connections become ever more important. Connections to family, friends, enemies and community. Its almost as if the energy to face loss is gathered from others.

These connections are hidden from health care, are often surprising and yet are such a valuable resource if only they are noticed. Doctors look at body parts, occasionally at the whole person, but almost never at the sustaining systems that surround people. Yet these systems can often be the clue to maintaining resilience or understanding distress in the face of advancing illness.

The Comfort of People reveals, in both technicolour and shades of grey, the ordinariness, the drama, the simplicity and the complexity of networks as people live out lives in the shadow of a serious diagnosis. These narratives of hospice patients, observed by an anthropologist, reveal the many ways in which people express themselves, choosing different media for different relationships: media such as Facebook to broadcast bulletins when close to death or Skype to connect with grandchildren around the world. The choice of communication channel seems to have meaning in terms of privacy, asymmetry, brevity and publicity. But ultimately these stories show that choices about communication and connection are pivotal to experiencing closure, and we should respect and understand the value and power of each face to face, text, phone or Facebook.

Many of the findings were surprising to me: the reticence to invite people into their house, the Englishness that Miller describes, contributes to a profound sense of isolation, even in a small village. People seem happier to connect in public spaces, or sometimes not at all. Miller observes that when the social relations of older people become attenuated, they cultivate their plants instead. The garden seems a huge source of comfort and distraction.

The issue of confidentiality is intriguing and highlighted in Marilyns experience in . Patients expect their vital medical information to be shared with all those who need to know yet the cult of confidentiality, as Professor Miller sees it, causes harm and frustration. It is quite remarkable that even as a patient is broadcasting details of her illness in a blog to the public, the doctor wont email her scan result to a neighbouring hospital. The devotion to fax machines has to change!

These stories need to be read by all those working with dying people. It is only in the process of dying that she has resolved one of her main conundrums of living: how best to use time. This insight from Miller jumped out at me.

We will be better healers if we realize the power, complexity and comfort of those in the patients social universe. We are learning to ask What matters to you?. These stories remind us to ask Who matters to you?.

Dr Ros Taylor MB, BChir, DL, MBE

Clinical Director, Hospice UK

Introduction

This is a book about peoples lives, not their deaths. It is a book about hospice patients, rather than the hospice. The primary aim is to provide a sense of the social connections of individuals who are diagnosed with a terminal, or long-term, illness that has led them to become patients of a hospice. The book explores the comfort of people, but also the wider consequences of the presence or absence of others. A secondary theme is the impact of contemporary media because this book arose from an academic project, studying the use of media. Many of these social contacts are routinely maintained at a distance. Because I am an anthropologist and understand what I observe in terms of norms and expectations, this is thirdly a book about Englishness.

The why and the how

I had no intention of carrying out research with hospice patients. At the time, I was in receipt of an advanced European Research Council grant for a five-year study of the use and consequences of social media around the world (Why We Post). This included an 18-month study of people living in a village north It was during my fieldwork that I was approached by Dr Helena, the hospice director, to conduct research within the hospice and make some applied recommendations, which are found at the end of this volume.

What I had not appreciated, prior to this research, was how perfectly Dr Helena embodied the ethos and spirit of the hospice movement itself. I recall watching her talk at periodic hospice meetings for potential patients and their carers. These meeting are critical for reframing the hospice experience. After all, the hospice is defined as a place you become associated with when you have received a terminal diagnosis. Soon after we began research, I bumped into an elderly man who referred to the hospice as the knackers yard, which is an old English expression for the profession that turned dead horses into substances such as glue and fertilizer hardly attractive connotations.