Acknowledgements

Thanks to: Jon Bryant, John Perring, Hanno and Marie-Christine, the Donkey Sanctuary, the Confraternity of St James, the Weed Science Society, Jessamy, Per, Brigitta, Simon, St John of Bedford, Jon Bjornsson, and Birna, Sn, Spons and Olbus Hispanicus. Also to most of my fellow pilgrims, and nearly all the people of northern Spain.

By the same author

FRENCH REVOLUTIONS

DO NOT PASS GO

One

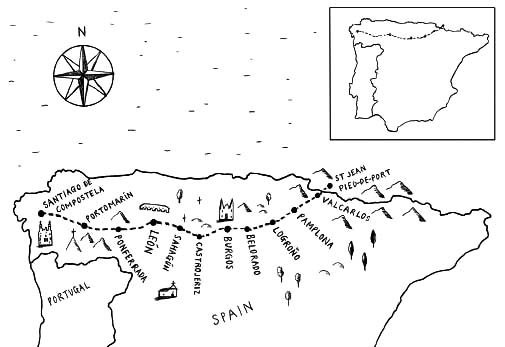

I ts 500 miles from St Jean Pied-de-Port on the French side of the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela near the north-western coast of Spanish Galicia. From the dawn of the last millennium until its final quarter, countless millions walked this route as the final leg of an epic hike from their own dusty thresholds, partly to stretch their legs in one of Europes most scenically appealing regions, and partly for remission of accumulated sins and a consequently more benign afterlife. Their goal was the cathedral in which were housed the crumbly mortal remains of Santiago, the patron saint of Spain: St James, as anyone who recalls Judith Keppels progress towards the first top prize on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? will be aware.

The fourth apostle recruited by Jesus, James was hardly an obvious choice for a thousand-year personality cult: so volubly stroppy his fellow fishermen nicknamed him and his similarly ill-tempered brother John sons of thunder, so petulantly arrogant he demanded to be placed at the Son of Gods right-hand side in paradise. When he was dispatched westwards by his doomed master on an evangelical mission, these attributes helped ensure that by the time James wound up on the left-hand tip of the Roman Empire, in north-west Spain, he had somehow managed to attract just seven disciples. That mouth clearly did him no favours after his return to the Holy Land: in AD 44 he became the first of the apostles to experience the afterlife, beheaded on the orders of Herod Agrippa.

Still, a martyr is a martyr, and after being sneaked out of Jerusalem, Jamess body was taken by sea to Galicia, terminus of his inefficient prophetic crusade. If I reveal that this voyage was made in an unmanned vessel hewn from solid marble, you will begin to understand that we are now on a voyage of our own: a journey beyond the shores of Factland, now gingerly skirting the Cape of Myth, now steaming gaily through the Straits of Arrant Cobblers. (Precisely where this figurative journey of ours set sail is a matter beyond sensitive debate, though for contextual ends Ill point out the lack of even biblical back-up for Jamess previous visit to Spain.)

Washed up on the beach a beach littered with the scallop shells that came to symbolise Santiago Jims hefty aquatic hearse is met by a divinely forewarned army of disciples, perhaps all seven of them. His body is promptly absorbed into a large stone slab, before being carted away by oxen for interment on a hillside significant only for its peculiar remoteness: an ox-whacking 25 miles from the shore.

Despite the many arresting features of its history, Jims final resting place is quickly lost, and lost so completely that it takes 750 years to find it. By then the Romans have given way to Visigoths, who in turn are handing over the Hispanic reins to the Moors, rushing up from North Africa with Europe-alarming haste: by the early eighth century, Spain finds itself almost completely under Muslim control. I say almost, for in their impatience to get at the French they overlook a few Christian huddles hunkered down in the northern mountains. One might draw parallels with Asterixs home village in Gaul, neglectfully unconquered by the surrounding Romans. And if one did, one would be more right than one supposed.

The embattled Christian guerrillas begin fighting back, assisted by Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor in waiting, who crosses the Pyrenees to harry the Moors. Yet its still proving difficult to form a front line across northern Spain, a bridgehead for the Christian Reconquest to start pushing the heathens back to Africa. If only there was something or someone to rally around, a figurehead to unify not only the various anti-Muslim factions in Spain, but focus righteous, fund-raising wrath across the Christian world. If only we could find some Whats that, old hermit type? You saw stars twinkling over a cave on a hillside? You went in there and dug up these bones? Here, Bishop Teodomiro, check this skelly out. Really? Well, thats a result. What about these other two? Fair enough. Hey, everyone: weve just found Santiago! And, like, a couple of other stiffs who are probably his disciples or something.

In a slightly random, Life of Brian way, it was all in place. Campus stellae, field of stars: Santiago de Compostela. The body of St James, a proper apostle, was one of the most prized relics in Christendom two of them, in fact, because along with the humble Santiago Peregrino, Pilgrim Jim, the pilgrims pilgrim, we now had the parallel promotion of Santiago Matamoros, James the Moor-slayer. Riding out of the sky astride his white charger, Big Bad Jim was regularly spotted dispatching the heathen foe in splendid profusion: no fewer than 60,000 kills to his name at the (probably fictitious) Battle of Clavijo in 852. A mascot for the cuddly Christians who sought to love their neighbours, and an insatiable psychopath for those whod sooner decapitate them.

It was this broad fan base, tempted from their homes by a praise-one-get-one-free pilgrimage, that made Santiago de Compostela one of the Christian worlds must-sees. The local king, Alfonso, built a church and monastery on the site, around which a city began to grow up. The first authenticated pilgrims arrived in the late ninth century, and by the mid-tenth the Camino de Santiago was already an institution. At its twelfth-century peak, with anti-Moor Christian fundamentalism rampant and the crusades in full flow, it has been estimated that between 250,000 and 1,000,000 pilgrims were arriving in Santiago every year; even more in a Holy Year, when Jims feast day, 25 July, fell on a Sunday. (By papal decree, pilgrims arriving in a Holy Year received total remission, a plenary indulgence, for all previous badnesses committed. Notch up the pilgrimage hat-trick Santiago, Rome, Jerusalem and you could build up a credit balance, Sin Miles redeemable against the perpetration of future wrongness.)

At a time when there were fewer than 65 million Europeans, with an average life expectancy of perhaps thirty-five, the demographic implications are arresting: by one calculation (yes its mine) between a fifth and a third of the medieval populace would at some time have paid personal homage to St James. As the Council of Europe noted when declaring the camino its first Cultural Route, the Compostela pilgrimage is considered the biggest mass movement of the Middle Ages.

Google-based curiosity was hardening into something like intent, and this new level of preparation was soundtracked by the weighty thump of footnoted product of academic industry on doormat. An early casualty of the reading was my Monty Python image of pilgrims as a brainwashed corpus of robotic, masochistic zealots: though that Get Out of Hell Free card was clearly top of the Santiago bill, it was difficult to generalise about the pilgrims motivations. The sick the horribly, medievally sick were lured by the hope of miraculous cure. So too the troubled: Thomas Becket himself recommended the pilgrimage to a woman who feared herself possessed by Satan. The curious came for education and adventure Chaucers Wife of Bath, no sombre devotee, visited twice in the late 1300s (accurately fictional, as lone women of good repute were a pilgrimage rarity). The naughty came to plunder this invitingly vulnerable tourist army, by violence or deception; and if they were caught, they might come again, as criminals given the option of walking to Santiago in lieu of a less appealing punishment. (Actually, theyd have been strung up and left to rot by the road on the medieval rap sheet only those guilty of less straightforward crimes would have been spared the noose, such as the Surrey adulteress who in 1325 was given the choice of visiting Santiago or being beaten with rods six times around various churches.)