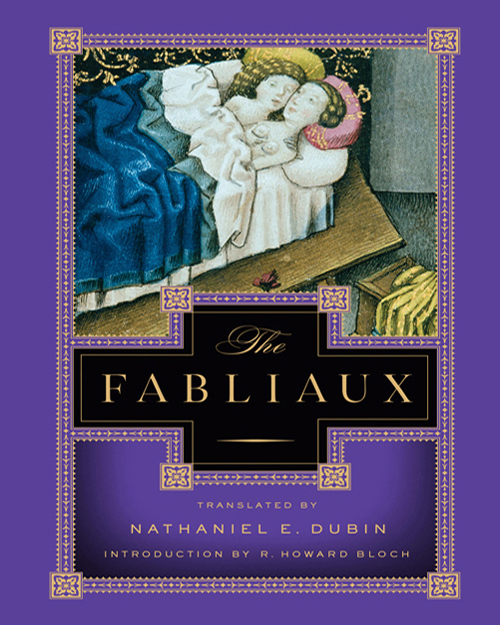

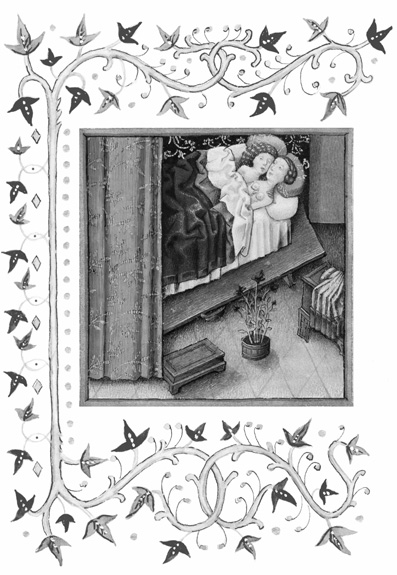

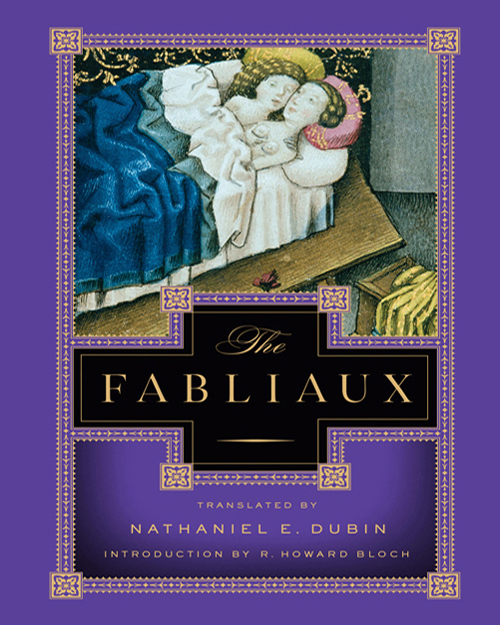

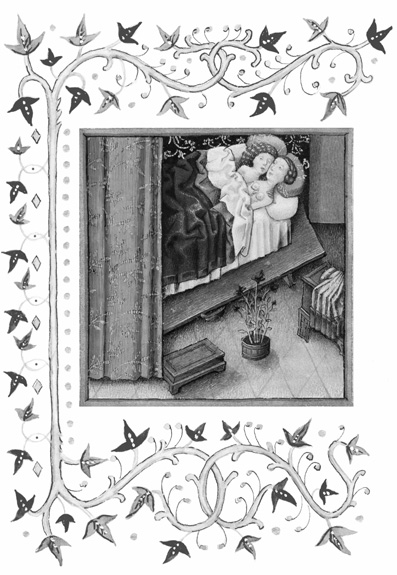

Frontispiece: The Consummation of Marriage . Illuminated manuscript page from Aegidi Colonna, The Trojan War in the Version of Martinus Opifex , 1445/50, Inv. Hs. 2273, fol. 18. Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Frontispiece: The Consummation of Marriage . Illuminated manuscript page from Aegidi Colonna, The Trojan War in the Version of Martinus Opifex , 1445/50, Inv. Hs. 2273, fol. 18. Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Photograph credit: bpk, Berlin / Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria / Art Resource, NY Decorative border: Judith Stagnitto Abbate Copyright 2013 by Nathaniel E. Dubin Introduction copyright 2013 by R. Howard Bloch All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W.

Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830 Manufacturing by RR Donnelley, Crawfordsville, VA Book design by Judith Stagnitto Abbate / Abbate Design Production manager: Anna Oler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The fabliaux : a new verse translation / translated by

Nathaniel E. Dubin ; introduction by R. Howard Bloch. First edition pages cm Includes bibliographical references. Poems in English with parallel Old French text. ISBN 978-0-87140-357-5 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-393-24052-8 (e-book) 1.

FabliauxTranslations into English. 2. French poetryTo 1500Translations into English. 3. Fabliaux. 4.

French poetryTo 1500.

I. Dubin, Nathaniel E., translator. II. Bloch, R. Howard.

III. English. English.

PQ1319.F25 2013 841'.03'08dc23 2013002314 Liveright Publishing Corporation 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www.wwnorton.com W. W. Norton & Company Ltd. Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT For my mother, the content of these tales notwithstanding C ONTENTS Please note that the ebook contains the English verse translation only. THE FABLIAUX THE OLD FRENCH comic tale in verse, or fabliau, lies at the origin of European realist literaturepart of that other Middle Ages opposed to the official culture and high-minded teachings of the Church on matters like money, food, and sex.

Scandalous at the time of their creation in the late twelfth century through the early fourteenth, they are still outrageous today. The fabliaux live on in the comic tradition of the West among the tales of Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Lope de Vega, as well as in the German Schwnke and the writings of Rabelais, Molire, and La Fontaine. They are the ancestors of the modern short story, especially of the drle type, those of Balzac, O. Henry, Mark Twain, or Maupassant. Yet the fabliaux themselves were virtually unknown between the sixteenth-century Renaissance and the rediscovery of the Middle Ages, beginning around 1830 in England, Germany, and France. Even then, they were read by only a handful of antiquarians and scholars.

Not until the present translation has a significant body of the fabliaux been available in a modern anthologyin French, English, or any languagefor the general reader. The richness of this collection, which surpasses even the most elaborate medieval manuscript, brings the comic tale to life, after eight hundred years, in a way that it has never lived at any moment in the past. There is, in the pages that follow, a wealth of surprise, enjoyment, and information about one of the great moments of turning in the West, and one of the formative stages in a world still recognizably our own. To understand just how important the fabliaux are, it is worth reviewing a bit the story of their discovery and the early history of their reception in nineteenth-century France. Carl von Clausewitz (17801831) famously wrote that war is a continuation of political relations by other means. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the Romantic rejection of the classical past and its stress upon universal man, the awakening nations of Europe turned to the Middle Ages as a way of asserting cultural and territorial claims.

Scholarship became a continuation of war by other means. The Germans discovered their great national epic, The Niebelungenlied , at the end of the eighteenth century and used this story of the defeat of the Burgundians by the Huns as a rallying cry after Napoleon vanquished them in 1806. The English discovered Beowulf in 1815, the very year the English and the Prussians defeated the French at Waterloo. Never mind that they originally thought it was written in Danish; by 1833, Beowulf had been translated into English. That was the year that Franois Guizot, French minister of public instruction, granted a scholarship of one thousand francs to a young man by the name of Francisque Michel for a literary voyage to England, with the understanding that Michel was to hunt for Old French manuscripts in English libraries and museums. On July 13, 1835, Michel discovered in Oxfords Bodleian Library what he believed to be the poem sung by Norman knights at the Battle of Hastings (1066), the French conquest of England, a feat of which Napoleon, who died in 1821, had dreamed of repeating as late as 1803.

The French had found, at last, their national epic, The Song of Roland , a seemingly oral poem written down around the time of the First Crusade (1096), which, in relatively short order, scholars began to compare with Homeric songa French Iliad , no less. The fabliaux did not fare as well as the epic when it came to making national identity. Though some had been published in the 1750s, and the wicked Diderot had anonymously transformed the tale of The Knight Who Made Cunts Talk into a satire of Louis XV in The Indiscreet Jewels ( Les Bijoux indiscrets ), the medieval comic tale did not become the subject of scholarly speculation until the middle of the nineteenth century. The fabliaux depict the enterprising, clever inhabitants of the towns of twelfth- and thirteenth-century northern France, an image of resourcefulness that, at first, appealed to the bourgeois leaders of the industrial and commercial revolution under the Second Empire (18521870). Those who would create modern secular France saw in this early version of their bourgeois selves an alternative to aristocratic ladies and knights, kings and courtiers, warrior bishops and pious hermits of the elevated Old French epic and chivalric romance. These literary types belonged to the Old Regime and no longer resonated with the interests and sympathies of a rising middle class.

However, scholars soon realized that the outrageously obscene, anticlerical, misogynistic fabliaux, which wildly violate any notion of bourgeois respectability, were an embarrassment, and hardly the stuff of national moral revival. Victor Le Clerc, author of volume 23 of the Benedictine Literary History of France (1856), simply refused to speak of the fabliau The Piece of Shit, in which a peasant woman manages to get her husband to eat a little dropping that she delicately lifts from under her skirt as the couple sits warming themselves around the fire during the long winters of northern France. By the time of the Franco-Prussian War (18701871), every effort was made to displace the origin of the medieval comic tale as far as possible from France. Gaston Paris, the father of medieval studies, was inspired by the Orientalist theories of German folklorists. He located the origins of the fabliaux in the Panchatantra , an ancient Sanskrit collection of animal fables, subsequently translated into Pehlvi, or Middle Persian, from which they were rendered into Syriac, Arabic, Hebrew, and, eventually, into Latin and various vernacular tongues in a long caravan of tales leading from India to France. The first editor of a complete edition in the original language, Anatole de Courde de Montaiglon, writing in the period just after the war with Germany and the beginning of the long wave of anti-Semitism that would culminate at the end of the century in the Dreyfus affair, stresses the semitic roots of the obscene tales in Old French.

Next page

Frontispiece: The Consummation of Marriage . Illuminated manuscript page from Aegidi Colonna, The Trojan War in the Version of Martinus Opifex , 1445/50, Inv. Hs. 2273, fol. 18. Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.

Frontispiece: The Consummation of Marriage . Illuminated manuscript page from Aegidi Colonna, The Trojan War in the Version of Martinus Opifex , 1445/50, Inv. Hs. 2273, fol. 18. Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria.