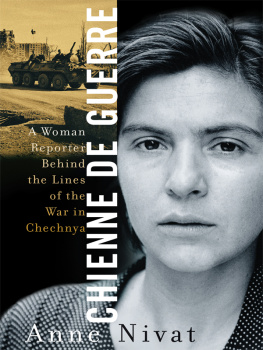

Nivat - Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war

Here you can read online Nivat - Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2001;2012, publisher: Public Affairs, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war

- Author:

- Publisher:Public Affairs

- Genre:

- Year:2001;2012

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nivat: author's other books

Who wrote Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Behind the Lines

of the War in Chechnya

Translated by Susan Darnton

Copyright 2001 by PublicAffairs.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a member of the

Perseus Books Group.

Endpaper map 2001 Jeffrey L. Ward

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, Suite 1321, New York, NY 10107.

Book design and composition by Mark McGarry, Texas Type & Book Works Set in Adobe Garamond

The French edition of Chienne de Guerre was published by Librarie Arthme Fayard, 2000.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nivat, Anne.

[Chienne de guerre. English]

Chienne de guerre / by Anne Nivat. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Translation from French; text is in English.

ISBN 1-58648-044-8

eBook ISBN: 9780786745579

1. Chechn (Russia)HistoryCivil War, 1994

2. Nivat, AnneJourneysRussia (Federation)Chechn. I. Title.

DK511.C37N5813 2001

947.5'2DC21 00-054739

FIRST EDITION

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To my Father

I would like to thank Bob Kaiser and Marvin Kalb who were not totally put off by my horrible stories from Chechnya, and who helped me find an American publisher; Andrew Paulson, who managed to keep in contact with me while I was in Chechnya; Fiona Hill, Sarah Mendelson, and Elin Suleymanov who understood what I was experiencing on the spot; Svetlana Alexeieff-Rockwell, Elena Levin, Frances Forte, Cheryl Hutchinson, and Lucille Wymer who didnt understand. It was better that way; they helped me recover. Lastly, thanks to Dan Williams and Lucia Annunciata. I had the immense and rare pleasure of writing these pages in their house on the island of Capri.

This book is an account of the war in Chechnya as I saw and lived it. At the time, I was working as a freelance reporter for two French dailies, Libration and Ouest-France. I had been living in Moscow for exactly a year. I was a young, inexperienced journalist, and I was having quite a hard time finding enough newspapers to print my stuff so that I could earn a living and establish my reputation. But I was thrilled to be realizing one of my earliest dreams: to be living and working in Moscow.

Russia had always been a shared passion in my family. My parents often invited Russian guests to our home for soires. Writers, artists, professors, and dissidents of all kinds passed through our villa, which was located in an area of France close to the Swiss border. My father, a professor at the University of Geneva, brought the Russians home with him, slipping them discreetly past the passport inspectors at the border (there were inevitably visa problems). As a child, I was fascinated by these bearded, rather wild-eyed men, who smelled of foreign cigarettes. Dinner lasted for hours and the table talk was entirely in Russian. Though I couldnt understand a word of it, this language sounded strangely familiar to my young ears. I was curious by nature, and I was eager to know what the adults were discussing. It was my mother who finally taught me Russian. She was a teacher in the secondary school of our provincial town. Six of us studied Russian together for five years. We passed the baccalaureate as a group.

I left my comfortable life in Paris with a doctorate in political sciencemy focus was Russian affairsin my pocket. I was twenty-five years old. Prague was my first destination. I spent the next three years in the Czech Republic, figuring out how to report from the field. This was my first encounter with Anglo-Saxon journalism, as its rather ironically known in France. I was working as a staff writer for Transitions, an English-language magazine published by George Soros and his Open Society Institute. Two people I met there played an influential role in my life: Michael Kaufman, who was enjoying a two years leave of absence from the New York Times to serve as editor-in-chief of the magazine, and Josephine Schmidt, then managing editor of Transitions, now on the staff of the New York Times These two mentors left me completely free to choose my own stories within the immense geographical area we covered, the ex-Communist countries of Europe and the former Soviet Union. They also edited the travel accounts I brought back from the field. My first trip to the Caucasus was as a reporter for Transitions. I traveled through Chechnya in 1996, at the end of the first Russian-Chechen war. I returned to the area at the end of January 1997 to witness the special presidential elections and the victory of Asian Maskhadov, the current Chechen pro-independence president whose legitimacy Moscow still refuses to recognize.

The hospitality of the people of the Caucasus, their customs and mores, struck a chord in me. I felt, as I often do when I am at some distance from the West, strangely safe and in touch with myself. The mountainous landscape reminded me of the Alps of my childhood. Perhaps this explains whyafter a years break as a Fulbright Fellow at Harvards Russian Research CenterI decided to return to southern Russia.

I was only sorry not to have returned sooner. For it is during the period between the two wars, from 1997 to 1999, where we must search for the seeds of the second Russian-Chechen conflict, a conflict that continues to this day. If we journalists ignore areas where nothing dramatic is happeningor where we imagine that nothing is happeninghow can we pretend to analyze conflict when it arises? I do not claim to understand the origins of the Russian-Chechen confrontation. I can only sketch its contours and paint to the best of my abilities a faithful picture of what I saw and experienced on the spot.

When Im in Russia, I travel alone as a matter of principle, war or no war. At the beginning of the present conflict, in September 1999, I applied for ad hoc accreditation as a war correspondent. When the Russians refused, I decided to cover the war from the Chechen side. I disguised myself as a Chechen woman, wrapping my body in layers of thick skirts, wool sweaters, and long scarves. Women are rarely noticed in Chechnya, and so I could be very discreet. People looked right through me or forgot I was there. And being fluent in Russian, I had no need of a translator. This was a great advantage. Of course, I presented myself as a journalist to those I interviewed officially, but if I could avoid it, I didnt introduce myself at all. I simply watched and listened. I was able to move about freely, avoiding the organized junkets the Russian Army put on for the foreign press. Travelling alone, or with a Chechen friend to help me negotiate my way through the hundreds of highway checkpoints, I kept my mouth shut. When I encountered Russian soldiers, I remained expressionless or I feigned exhaustion, leaning my head against the dirty car window as I waited through yet another perfunctory border control. I learned to anticipate the behavior of the Russians on duty, to have a ready response to any emergency. I knew I could retrace my steps if necessary or reveal my identity and profession. Fortunately and I had a lot of good fortune during these six monthsI never once had to turn back. That being said, in the midst of a full-scale war, it is always too late to turn back or to hide, and so I stayed.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war»

Look at similar books to Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Chienne de guerre: a woman reporter behind the lines of the war and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.