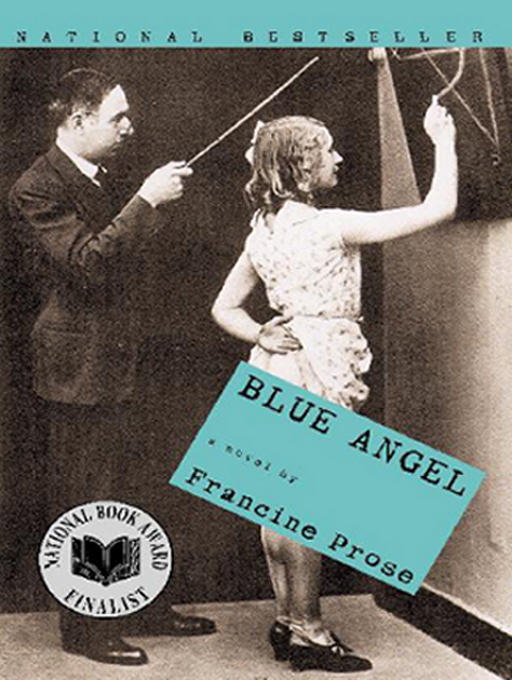

Blue Angel

a novel

Francine Prose

To Howie

rituals, adjusting zippers and caps, arranging the pens and notebooks so painstakingly chosen to express their tender young selves, the fidgety ballets that signal their weekly submission and reaffirm the social compact to be stuck in this room for an hour without real food or TV. He glances around the seminar table, counts nine; good, everyones here, then riffles through the manuscript theyre scheduled to discuss, pauses, and says, Is it my imagination, or have we been seeing an awful lot of stories about humans having sex with animals?

The students stare at him, appalled. He cant believe he said that. His pathetic stab at humor sounded precisely like what it was: a question hed dreamed up and rehearsed as he walked across North Quad, past the gothic graystone cloisters, the Founders Chapel, the lovely two-hundred-year-old maples just starting to drop the orange leaves that lie so thickly on the cover of the Euston College viewbook. Hed hardly noticed his surroundings, so blindly focused was he on the imminent challenge of leading a class discussion of a student story in which a teenager, drunk and frustrated after a bad date with his girlfriend, rapes an uncooked chicken by the light of the family fridge.

How is Swenson supposed to begin? What he really wants to ask is: Was this story written expressly to torment me? What little sadist thought it would be fun to watch me tackle the technical flaws of a story that spends two pages describing how the boy cracks the chickens rib cage to better fit the slippery visceral cavity around his throbbing hard-on? But Danny Liebman, whose story it is, isnt out to torture Swenson. Hed just wanted something interesting for his hero to do.

Slouched over, or sliding under, the seminar table, the students gaze at Swenson, their eyes as opaque and lidded as the eyes of the chicken whose plucked head the hero turns to face him during their late-night kitchen romance. But chickens in suburban refrigerators are generally headless. Swenson makes a mental note to mention this detail later.

I dont get it, says Carlos Ostapcek. What other stories about animals? Carlos always starts off. Ex-navy, ex-reform school, hes the alpha male, the only student whos ever been anywhere except inside a classroom. As it happens, hes the only male student, not counting Danny.

What stories is Swenson talking about? He suddenly cant recall. Maybe it was some other year, another class completely. Hes been having too many moments like this: a door slams shut behind him and his mind disappears. Is this early Alzheimers? Hes only forty-seven. Only forty-seven? What happened in the heartbeat since he was his students age?

Maybe his problems the muggy heat, bizarre for late September, El Nio dumping a freak monsoon all over northern Vermont. His classroomhigh in the college bell toweris the hottest spot on campus. And this past summer, workmen painted the windows shut. Swenson has complained to Buildings and Grounds, but theyre too busy fixing sidewalk holes that could result in lawsuits.

Is something wrong, Professor Swenson? Claris Williams inclines her handsome head, done this week in bright rows of coiled dyed-orange snails. Everyone, including Swenson, is a little in love with, and scared of, Claris, possibly because she combines such intelligent sweetness with the glacial beauty of an African princess turned supermodel.

Why do you ask? says Swenson.

You groaned, Claris says. Twice.

Nothings wrong. Swensons groaning in front of his class. Doesnt that prove nothings wrong? And if you call me Professor again, Ill fail you for the semester.

Claris stiffens. Relax! Its only a joke! Euston students call teachers by their first names, thats what Euston parents pay twenty-eight thousand a year for. But some kids cant make themselves say Ted, the scholarship students like Carlos (who does an end run around it by calling him Coach), the Vermont farm kids like Jonelle, the black students like Claris and Makeesha, the ones least likely to be charmed by his jokey threats. Euston hardly has any students like that, but this fall, for some reason, theyre all in Swensons class.

Last week they discussed Clariss story about a girl who accompanies her mother on a job cleaning a rich womans house, an eerily convincing piece that moved from hilarity to horror as it chronicled the havoc wreaked by the maid stumbling through the rooms, chugging Thunderbird wine, until the horrified child watches her tumble downstairs.

The students were speechless with embarrassment. They all assumed, as did Swenson, that Clariss story was maybe not literal truth, but painfully close to the facts. At last, Makeesha Davis, the only other black student, said she was sick of stories in which sisters were always messed up on dope or drunk or selling their booty or dead.

Swenson argued for Claris. Hed dragged in Chekhov to tell the class that the writer need not paint a picture of an ideal world, but only describe the actual world, without sermons, without judgment. As if his students give a shit about some dead Russian that Swenson ritually exhumes to support his loser opinions. And yet just mentioning Chekhov made Swenson feel less alone, as if he were being watched over by a saint who wouldnt judge him for the criminal fraud of pretending that these kids could be taught what Swensons pretending to teach them. Chekhov would see into his heart and know that he sincerely wished he could give his students what they want: talent, fame, money, a job.

After the workshop on her story, Claris stayed to talk. Swenson had groped for some tactful way to tell her that he knew what it was like to write autobiographically and have people act as if it were fiction. After all, his own second novelAs hard as this is to believe, he hadnt realized how painful his childhood was until his novel about it was published, and he read about it in reviews.

But before he could enchant her with the story of his rotten childhood and his fabulous career, Claris let him know: Her mom is a high school principal. Not a drunken domestic. Well, shed certainly fooled Swenson, and done a job on the class. Couldnt she have dropped a hint and relieved the tension so thick that it was a relief to move on to Carloss story about a dreamy Bronx kid with a crush on his neighbor, a tender romance shattered when the heros friend describes peeping through the neighbors window and seeing her fellate a German shepherd?

That was the other story about animal sex. Swenson hasnt imagined it, and now he remembers the one before that: Jonelle Brevards story about a Vermont farm wife whose husband keeps calling out his favorite cows name in his sleep. Three animal sex stories, and the terms just begun.

Your story, for one, Carlos. Was I imagining the German shepherd?

Oof, says Carlos. I guess I forgot. The class laughssly, indulgent. They know why Carlos repressed it. The discussion of his story had devolved into a shouting match about sicko male fantasies of female sexuality.

This class has only been meeting five weeks, and already they share private jokes and passionate debates. Really, its a good class. Theyre inspiring each other. Theres more energy in this bestiality thing than in years of tepid fiction about dating mishaps or kids with divorced dysfunctional parents drying out from eighties cocaine habits. Swenson should be grateful for student work with any vitality, any life. So why should he insist on seeing these innocent landscapes of their hearts and souls as minefields to pick his way through?