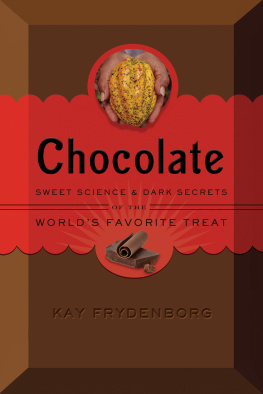

That was no exaggeration; I was a chocolate ignoramus. Except maybe at dessert time (or often during any day, mornings and late nights included), I never thought much about the stuff. John Glusman, my editor, and Geri Thoma, my agent, had the confidence to think I could fill a book on the subject. But I couldnt have come close without Chlo Doutre-Roussel.

Generosity poured in from all sides. Aodaoin OFloinn covered my back. Hadley Fitzgerald sent books, wisdom, clippings, and energy. So did Gretchen Hoff, Willis Barnstone, Phil Cousineau, and Barbara Gerber. Louis and Paul Kay, and their parents, showed me some basics. David Lebovitz was generous with prodigious knowledge and time despite work on a book of his own. Sophie Body-Generot and Kerrin Feldman got me started. Olivia Snaije, Daphne Benoit, Ariane Troujman, Cecile Allegra, Linda White, Pan Kwan Yuk, Jerome Delay, and a lot of others helped along the way. The aid of Claudio and Steve and other chocolate masters is evident in the text.

Above all, of course, there is Rose, ne Jeannette Hermann, who fed the process, from start to finish, and then helped clean up the mess.

THE GODS BREAKFAST

A half millennium ago, a canoe full of Indians rowed out to an ungainly floating house anchored at Guanaja, a palm-flecked island off the Honduran coast. Christopher Columbus had stopped by on the way home from his fourth and last trip to America, still hopeful he might find useful riches beyond an expanse of alien real estate. The Indians offered what he took to be a handful of shriveled almonds. He was mystified when a few dropped to the bottom of their canoe, his son reported later, and they scrambled for them as though they were eyes that had fallen out of their heads. But Columbuss Mayan was no better than the natives Spanish. He returned to Spain empty-handed.

Chocolate has come a long way since then.

These days, those almondlike cacao beans that the grand Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus named Theobroma elixir of the godsare the basis of a $60 billion industry. From the time laborers scoop them from pods in equatorial jungles until fine chocolatiers massage them into gold-flecked ganaches, the value of a bean might increase several hundred times. But money is hardly the way to measure their worth.

One night in Paris, a friend took me to a tasting of the Club des Croqueurs de Chocolat, a circle of people who believe well-craftedbonbons to be as vital to life as oxygen. We tried one creation after another, noting every nuance from the sheen on their coatings to subtle flashes of flavor that lingered on the tongue. With knowing nods and silent smiles, we made checks on evaluation sheets next to adjectives borrowed from the complex lexicon of wine.

Finally, sated to near stupor, we settled back to hear the tastemaster announce plans for the next session. We would, he said, be sampling the finest eclairs au chocolat that France had to offer.

Ah, oui, one woman breathed from the back of the room. Oouuiii , another added, with more power, and a third joined in with loud staccato moans: Oui, oui, oui. Suddenly the sedate hotel dining room was blue with the piercing shrieks of passion. Columbus would have loved it.

Like every other American kid, I grew up on Hershey bars and those colorful little blobs that, M&Ms claims aside, melted in my hand as well as in my mouth. Over the years, as an amateur food lover and professional traveler, I learned to appreciate other variations on the theme. That evening in Paris, however, showed me I was clueless, a chocolate ignoramus.

Tracing chocolate from its origins to its most elaborate final forms, I suspected, would be a wondrous journey. But only after I followed cacao into a fierce African rebellion and then stood paralyzed with pleasure at the heady scent inside Michel Chauduns little shop in the seventh arrondissement of Paris did I realize how much chocolate has flavored the last five centuries.

I started out by paging at leisure through Roald Dahls Charlie and the Chocolate Factory . Before long, I was delving into the themes of War and Peace .

By the end, I saw why people like my friend Hadley Fitzgerald, a California therapist of reasonable habits, would have to think a moment if the devil offered to buy their souls for chocolate. Hadleys body and being require a daily dose.

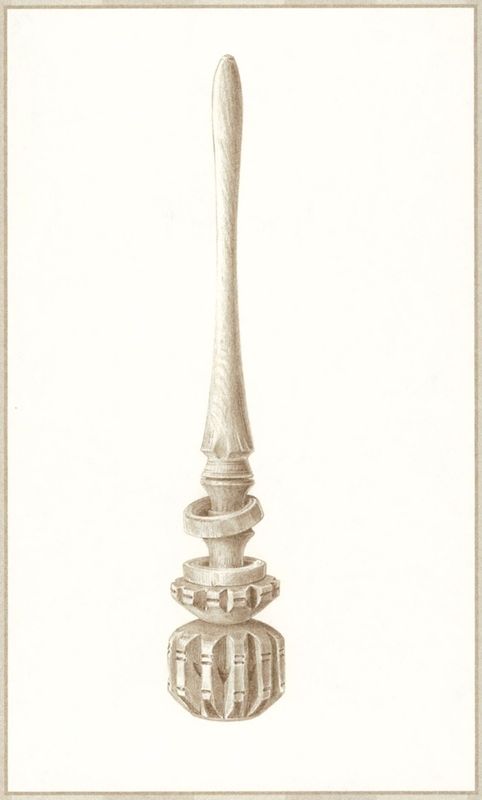

Taken to its highest finish, cacao ends up as a palet dor , a simple square or circle of creamy dark fillingthe French call that ganacheinside a thin, hard covering of silky smooth chocolate,the enrobage. At its best, a palet dor shines with a rich brilliance. And it is signed by its maker in bits of real gold, which carry no taste but deliver an unmissable message: This is the good stuff.

I began to catch on when I savored two palets made with distinct types of chocolate from the French company Valrhona. One was Manjari, from Madagascar cacao; the other was from Gran Couva plantation in Trinidad. Except for cream in the ganache, both palets were pure chocolate.

The Manjari came in a rush of ripe raspberries. It peaked and then settled into a long, lush finish. Gran Couva was flowers, not fruit, a slow-moving cloud of jasmine that carried me away to some very happy place.

Nothing is simple about good chocolate. Some high practitioners prefer the term palet or . Either way, the old translation was pillow of gold. According to the Acadmie Franaise des Chocolatiers et Confiseurs, Bernard Serarady devised the name in 1870, in the town of Moulin. But Saint-Germain-en-Laye disputes that claim. In 2004, French chocolatiers convened to argue the point.

Soon I dispensed with the fancy final product and bought bulk chocolate bits from my favorite producers in the Rhone Valley, in Tuscany, in Californias Bay Area. In form, though in no other way, these reminded me of those baking chips I used to forage from my mothers pantry.

Beyond industrial candymakers with brands we all recognize, chocolatiers come in two flavors. There are those who make chocolate from beans, from the Swiss-based behemoth Barry Callebaut to such specialists as Valrhona. And there are artisans known as fondeurs the word means melterswho turn this base chocolate into high art.

France bestows upon its chosen chocolatiers the aura of philosopher-kings. Pierre Herm, a hulking bull of a man with a delicate touch, opened his small Parisian shop on the rue Bonaparte and had to hire a press agent to ward off the journalistic swarm. Robert Linxe sold his redoubtable La Maison du Chocolat in Paris to a globe-girdling French industrialist, yet eager pilgrims still come to sit at his feet.