Introduction

A Modern Frontier

The West is a place for adventurers and early adopters. It embraces the new. However, the vast stretch of North American West from Wyoming down to Arizona and out to the Pacific Coast, which the late author Wallace Stegner described as still forming, shining and new, is also infused with a Mesoamerican and Spanish Missionary spirit.

Those ancient strains meld neatly today with an effervescent modernity that is epitomized in the work of technology pioneers in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Pacific Northwest, by maverick performers and skateboarders alongside equally exhibitionist buildings on the boardwalk in Venice, California, where an artist community that included Ed Moses, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Ed Ruscha has long thrived, and by the boundless, futuristic imagination of Hollywood.

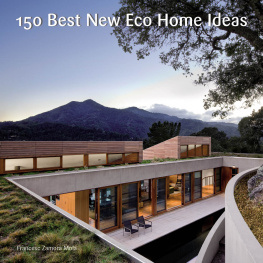

The homes included in this book represent the hybrids of old and new that periodically emerge along the coast, in deserts, up mountains and even across the ocean, where, for instance, Mexican-style courtyards morph into island lanais.

Early twentieth-century Southern California buildings by giants such as Irving Gill and architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose influence spread from his Taliesin School in Scottsdale, Arizona, all the way to Hawaii and Japan, have had many descendants. Some of Wrights experiments with humble cinder block, such as his 1924 Ennis House in Los Angeles that consciously echoes the patterns and massing of Mayan temples and the sheltered courtyards of Mexican ranchos, are seminal. Austrian architects Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, who adopted Los Angeles as home, admired, like Wright, Californias breathtaking vistas and existing hybrid vocabulary and added to it their version of the clean-lined International style. They influenced others, such as Gregory Ain, whose modest, proletarian open-plan courtyard homes suited for clement weather became a part of the broad western vernacular that would later fill expanding suburbs.

In Los Angeles, California, skateboarders at a Venice Beach rink symbolize the areas free-spirited art community.

Nearby, architect Frank Gehrys 1984 Venice Beach house for Bill and Lynn Norton is another iconoclastic landmark.

As the West commemorates the 75th anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridgeits symbolic gateway to modernityit also recognizes the catalytic effect of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor just five years after the bridge was built. That act transformed the relatively isolated West Coast into an armed frontier with bunkers ready for war. New suburbs for soldiers on the coast rapidly replaced farmland and orchards, and by the end of World War II, California, Oregon and Washington, as well as their neighboring states, emerged as a thriving, modern international frontier between east and west with clusters of ranch-style homes.

Among them, Cliff Mays typical ranch-style designs evolved from his San Diego familys Hispano-Moresque courtyard home and his own European, Spanish Colonial and Mexican roots. Built with only some discernible Mediterranean and North African Moorish features to interrupt wood-framed stucco walls, large expanses of glass, low-slung roofs and broad verandahs, Mays light-filled courtyard ranch houses shaped for modern open-plan indoor/outdoor living still resonate as new.

In 1945, when Arts & Architecture magazine editor John Entenza promoted the Case Study program to further improve the look of suburban buildings, more polished hybrids surfaced from the studios of architects Neutra, Schindler, Ray and Charles Eames, and many others, effectively influencing developers like Joseph Eichler in Northern and Southern California. Their prefabricated courtyard bungalows made wood, steel and concrete the new adobe.

Architects and developers incorporated clean-lined International style strictures pragmatically and incrementally to create regional arcadian suburbia, as Gwendolyn Wright, professor of architecture at Columbia University, succinctly describes in her foreword to Eichler: Modernism Rebuilds the American Dream.

An artist community embraces graffiti in Venice, California, where a beachside wall has been reserved for the art form.

As if echoing her Southern California roots, San Francisco Bay Area art collector Chara Schreyer showcases art as arresting as graffiti, including floor art called In Between False Comforts by Robert Melee, an exploded Barbie dress in a cage by E. V. Day called Bridal Supernova 1, and, in the niche, Pierre-Louis Piersons La Comtesse de Castiglione (Cactus).

Away from the glare of Hollywood, two semisuburban buildings remodeled by the Santa Monica firm Daly Genik face each other across a central courtyard that is entered through a side gate from the street. The atypical site plan reflects other Mediterranean and North Africanstyle courtyard precedents along the Spanish Mission Trail. Filigreed, painted metal scrims like Arab