ALLEN LANE

an imprint of Penguin Canada Books Inc., a Penguin Random House Company

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Canada Books Inc., 320 Front Street West, Suite 1400, Toronto, Ontario M5V 3B6, Canada

Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published in Allen Lane hardcover by Penguin Canada Books Inc., 2016. Simultaneously published in the U.S.A. by Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Copyright Laura Secor, 2016

Verses from Mohammad Mokhtari, From the Other Half, in English translation are reprinted by permission of Arcade Publishing, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Secor, Laura, author

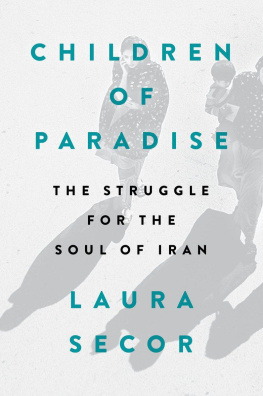

Children of paradise : the struggle for the soul of Iran / Laura Secor.

Co-published by: Riverhead.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-670-06798-5 (bound)

1. IranPolitics and government19791997. 2. IranPolitics and government1997. 3. IranHistory19791997. 4. IranHistory1997. 5. IranIntellectual life20th century. 6. IranIntellectual life21st century. I. Title.

DS318.8.S42 2016 955.05'4 C2015-906536-4

eBook ISBN 978-0-14-317308-3

American Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data available

Visit the Penguin Canada website at www.penguin.ca

Special and corporate bulk purchase rates available; please see www.penguin.ca/corporatesales or call 1-800-810-3104.

Version_1

F OR G EORGE, C HARLIE, AND J ULIA

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

I WAS A CHILD when Iranian students overran the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took its personnel hostage for 444 days. It was the first international news event to enter my consciousness. On television, Tehran appeared to be a city of unmoving traffic and mobs of very riled-up young people burning American flags. I had urgent vocabulary questions. What was an embassy? What was a hostage? But the images and emotions I understood. Somewhere on the other side of the world, there was a forbidden country entangled deeply and inextricably enough with my own to produce a hostility that stunned the anchors of the network news.

For Americans of my generation, Iran was the object of fearful caricature, the worlds first Islamic theocracy, with a dour ayatollah at the helm. Iran was a foreign policy conundrum to be solved and a black box whose contents were all but unknowable. After 1979, Americans seldom traveled there, and press reports of any depth were surprisingly rare. When I became a journalist, such places intrigued and compelled me. The privilege of being a correspondent, after all, was to go places where one didnt belong. Iranian visas were notoriously difficult to come by; in 1999 a New Yorker story by the journalist Robin Wright portrayed Iran as a country so compelling that I realized Id one day have to try to get one.

I knew that Irans recently elected president, Mohammad Khatami, had pledged to reform the countrys autocratic regime. But I hadnt imagined that behind the frozen images from 1979 lay a vibrant, soul-searching country. Student activists, who still used looted American embassy letterhead for copier paper, defended newspapers from censorship, and philosophers reached for new theories to reconcile liberal rights with an Islamic state theyd helped coax into being. One of the lead hostage takers in 1979 had become a proponent of democratic reform and now devoted his time to traffic issues on Tehrans city council. It was as arresting a reversal as it was unlikely. Revolutionary ideology had limits, the city councilman explained. It could not solve mundane urban problems. Behind this simple assertion, I was certain, was a universe of context: two decades of experience in the life of a nation and the life of that man, but surely also a shift in the intellectual climate that made it possible to speak of democratic change and of the city council as its humble instrument.

I had never been to the Middle East. I was a writer and editor at Lingua Franca magazine, which covered intellectual life and academic politics, and at the time I was working on a story of my own about the former Yugoslavia. The dissident intellectuals in my piece had followed what seemed the opposite of the Iranian trajectory, from reformist critique within communism to a ferocious and exclusionary nationalism that tore their country apart. Here again was a country after my heart, as I had come to know itone where ideas mattered, and where history was so compressed as to be indistinguishable from the biographies of the people who made it. I was pretty sure my editor at Lingua Franca had read the New Yorker piece, too, when he looked up from editing mine to remark offhandedly that he expected the two of us to reconvene in his office one day to work on a story about Iran.

I started to collect all the scholarly books about Iran that crossed the magazines transom. There would be time, and other subjects, before I got to them, but Iran was the dream story for a writer who loved the things I loved.

I STARTED VISITING I RAN IN 2004. The atmosphere was more oppressive than Id imagined. The excitement over reform had obscured the conditions that rendered such political relaxation so necessary. What I encountered probably would have been familiar to anyone who visited the old Soviet bloc in days gone by, and it was undoubtedly less severe than in many neighboring countries. Still, this was a closed country, and no honest accounting for its politics could fail to acknowledge the fact.

Even ordinary Iranians made the practical assumption that their phones were tapped and e-mails read. Sensitive meetings were best arranged through elaborate chains of in-person contacts. Some of my interview subjects were routinely followed; others received harassing phone calls or were forced to report continually to the men whod interrogated them in prison. A merchant I met in the bazaar slipped me a note to see him privately, which I did, on a busy street corner, where, sotto voce, he explained the layers of political control within his workplace.