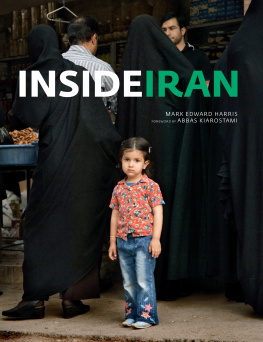

My extreme gratitude to my friends and colleagues Mehrdad, Nasrin, Hossein Farmani, Anna Bolek, Sheila and Bob Harris, Rikke Nielsen, Kelly Wearstler, and Patricia Gajo, as well as to Steve Mockus for his editing skills, and to Azi Rad for her thoughtful design. Grateful thanks also to James Felder, Jocelyn Miller, Adrian Curry, Ahmad Kiarostami, and Abbas Kiarostami.

FOREWORD BY ABBAS KIAROSTAMI

I have to confess that I never liked the term nature morte (meaning still life, literally: dead nature), as it always seemed like an oxymoron to me. Even looking at a dead bird does not remind me of dead nature. In fact, it seems more representative of a special event in the cycle of lifea special event with a feel of magic. There is always something magical about life and death, and something even more magical about fixing one special moment, which may apparently have nothing special about it, forever.

So many times, I have witnessed the introduction of a strange upheaval into the heart of everyday life, an unusual presence in the midst of the well-known scenery, and god knows how thankful I have been at that special moment for having my friend the camera with me, and for being able to move a finger and make the fatal click once again. Each time I take a photograph, it is a version of the same experience; not only have I once again easily accepted the intrusion of magic into the realm of reality, but I have been able to fix that moment forever. That is why, to paraphrase a character of Thomas Bernhards, I snuck into art to get away from life. And what a getaway! This in spite of the fact that life eventually catches up to you.

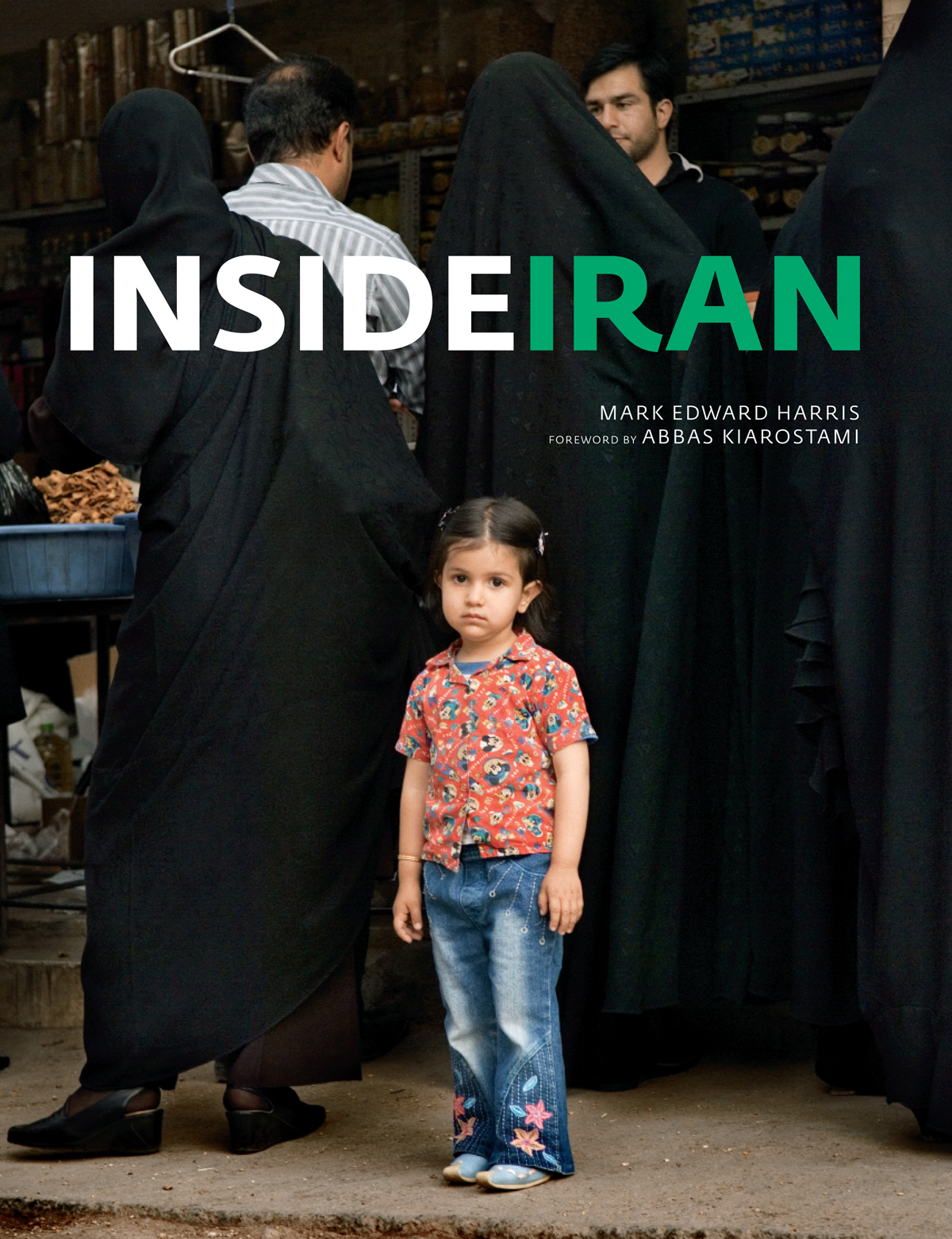

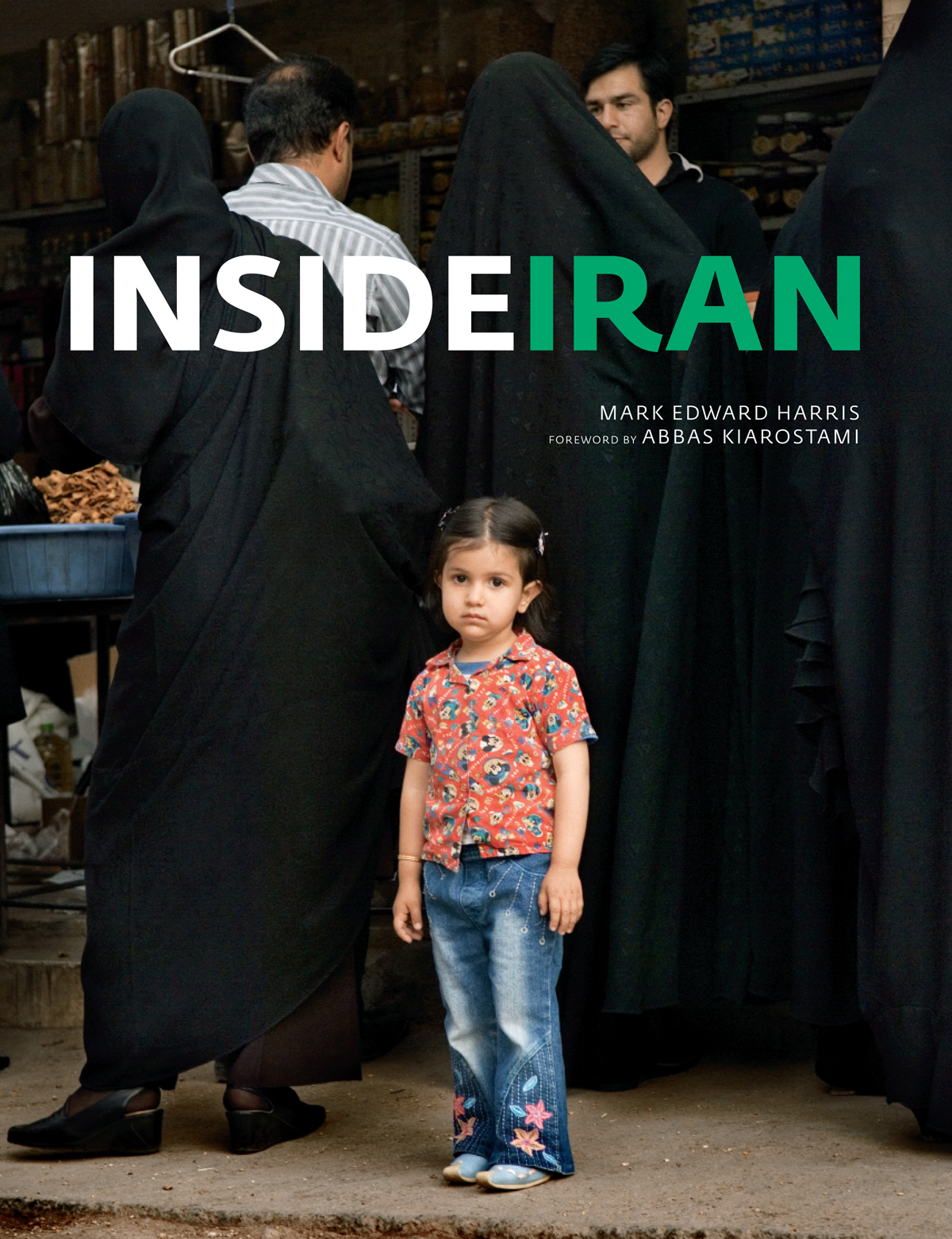

While looking at the photographs in this book, it surprised me that I was especially enjoying the presence of human beings in the pictures, something that I purposely avoid in my own photographic work. In this collection I enjoyed the magical presence of contemporary moments placed in a historical context. I know those kids in the photographs; they are the same all around the world. And I know those historical monumentsthe pride of the land, they all look the same, too. Suddenly, I got the strange feeling of seeing much more than simple photographs. To me, the pictures represented the great challenge of this century: the temporal versus the eternal. And the message was now obvious to me. Once again, we have to choose life!

They say that one has to write with his ear; well, Mark Edward Harris definitely took these photographs with his heart. This is why we can look at these pictures and hear the stories they have to tell us. They are not just moments captured in the flow of time. This is not still photography. The photographs in this book choose life; the life that catches up with you, unexpectedly, even exactly where and when you want to get away from it. A photograph is not the image of an illusion, nor the representation of the real. Reality does not disappear under a scrutinizing eye; it just tells us its story. Lets listen to it.

It was with more than a little trepidation that I boarded the IranAir 747 at Londons Heathrow Airport bound for Tehran in spring 2007. A group of fifteen British sailors and marines had just been released by the Islamic republic after having been captured by Iranian forces just two weeks earlier in the mouth of the Shatt al Arab waterway that separates Iran and Iraq (they had been accused of illegally entering Iranian waters). It was yet another diplomatic crisis at a time when tensions over Tehrans nuclear ambitions were already setting up the potential for an armed conflict.

Having been named a member of the axis of evil in U.S. President George W. Bushs State of the Union address in 2002, having seen what had already happened to another member of the triumvirate, Iraq, and having witnessed the rhetoric going on between North Korea and the United States, how would the Iranian citizenry feel about an American traveling freely around their country, especially one armed with professional photographic equipment? Several Americans of Iranian descent were already being held in the country, accused of spying for the United States.

I had previously traveled to North Korea, in 2005 and 2006, with a similar goal in mind. I wanted to document scenes of daily life little seen or understood by the West at a time of heightened tension, when it seemed all the more important to see what peoples lives were like in a country whose future was likely to be played out in a geopolitical chess game. President Bushs declaration that states like these [Iraq, Iran, North Korea], and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world, gave me an inescapable sinking feeling that the United States was sliding into a very deep chasm from which it would be difficult to extricate ourselves.

Iran is among the eighty countries I have had the good fortune to explore with my camera, hopefully with an open mind. I have been in many other areas of political conflict, including the former Soviet Union, East Germany, Vietnam, Cuba, Lebanon, Israel, the two Irelands, and the two Koreas. Ive been surprised every time by what I have seen and experienced.

After landing at Tehrans Mehrabad Airport, I spent several weeks traveling 7,000 miles on the ground, emerging from Iran with a very different impression from the one I had going in. Life on the streets was much more vibrant and open than I had expected. While many peopleboth in Iran and in the outside worldsee the chadors and burqas as a physical manifestation of oppression, the business and social interactions I witnessed between the sexes did not quite match up. I was surprised to see women running restaurants and acting as contractors on construction sites. To be sure, the difference was more marked between the cities and the remote areas of the country (from which the ruling mullahs draw much of their support), where women were dressed more conservatively, but this distinction in itself was something of a revelation to me, and I wanted to learn more.

On my first visit to Iran, I explored the heart of the country, including the historic cities of Qom, Kashan, Shiraz, Isfahan, and Yazd, and the ruins of Persepolis. I returned several months later to retrace some of my steps and to cast farther afield, traveling to the Persian Gulf, the Caspian Sea, and the Afghan and Iraqi border regions.

Iran is a socially and politically complex country of some 70 million people, with a long, rich, and complicated history. I hope that this book will in its way contribute to a more engaged curiosity about and perhaps a better understanding of this fascinating place in the world.

A truck at a gas station near Kashan displays Irans colors: green representing Islam, white standing for peace, and red symbolizing courage. The words written in Arabic are There is no God but Allah.

CHAPTER 1

TEHRAN

MORE THAN 14 MILLION PEOPLE LIVE IN IRANS SPRAWLING CAPITAL CITY, 4,000 FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL IN THE SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS OF THE ALBORZ MOUNTAIN RANGE.

A view of Tehran including the Milad Tower, part of Tehrans international trade and convention center, from the top floor of the Laleh (tulip) International Hotel.

Tehran, like the rest of Iran, is not how we see it typically depicted in Western media. Since the takeover of the U.S. Embassy in 1979 and the ensuing hostage crisis, we have been exposed to pictures of anti-American murals, women trolling the streets covered in black chadors, and the occasional street execution. This is a small part of a much bigger picture. What we do not see are the throngs of young people hanging out in teahouses, pizza parlors, and shopping malls, or commuting to and from school and work, or mothers and fathers interacting with their childrenin other words, scenes of daily life.