Laura Secor - Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran

Here you can read online Laura Secor - Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Riverhead Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran

- Author:

- Publisher:Riverhead Books

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Laura Secor: author's other books

Who wrote Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2016 by Laura Secor

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Verses from Mohammad Mokhtari, From the Other Half, in English translation are reprinted by permission of Arcade Publishing, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

eBook ISBN 978-0-698-17248-7

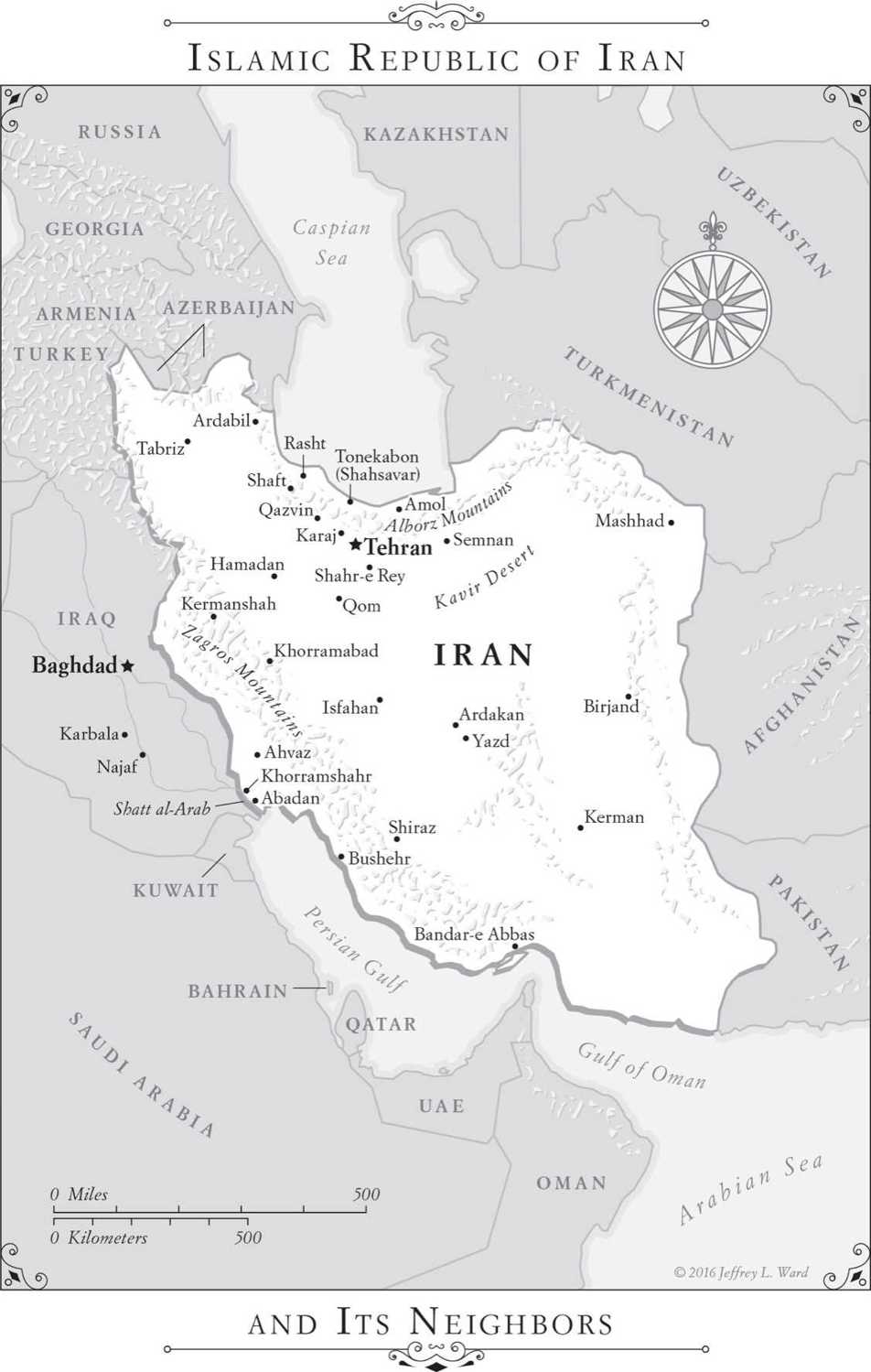

Map byJeffrey L. Ward

Version_2

F OR G EORGE, C HARLIE, AND J ULIA

I WAS A CHILD when Iranian students overran the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took its personnel hostage for 444 days. It was the first international news event to enter my consciousness. On television, Tehran appeared to be a city of unmoving traffic and mobs of very riled-up young people burning American flags. I had urgent vocabulary questions. What was an embassy? What was a hostage? But the images and emotions I understood. Somewhere on the other side of the world, there was a forbidden country entangled deeply and inextricably enough with my own to produce a hostility that stunned the anchors of the network news.

For Americans of my generation, Iran was the object of fearful caricature, the worlds first Islamic theocracy, with a dour ayatollah at the helm. Iran was a foreign policy conundrum to be solved and a black box whose contents were all but unknowable. After 1979, Americans seldom traveled there, and press reports of any depth were surprisingly rare. When I became a journalist, such places intrigued and compelled me. The privilege of being a correspondent, after all, was to go places where one didnt belong. Iranian visas were notoriously difficult to come by; in 1999 a New Yorker story by the journalist Robin Wright portrayed Iran as a country so compelling that I realized Id one day have to try to get one.

I knew that Irans recently elected president, Mohammad Khatami, had pledged to reform the countrys autocratic regime. But I hadnt imagined that behind the frozen images from 1979 lay a vibrant, soul-searching country. Student activists, who still used looted American embassy letterhead for copier paper, defended newspapers from censorship, and philosophers reached for new theories to reconcile liberal rights with an Islamic state theyd helped coax into being. One of the lead hostage takers in 1979 had become a proponent of democratic reform and now devoted his time to traffic issues on Tehrans city council. It was as arresting a reversal as it was unlikely. Revolutionary ideology had limits, the city councilman explained. It could not solve mundane urban problems. Behind this simple assertion, I was certain, was a universe of context: two decades of experience in the life of a nation and the life of that man, but surely also a shift in the intellectual climate that made it possible to speak of democratic change and of the city council as its humble instrument.

I had never been to the Middle East. I was a writer and editor at Lingua Franca magazine, which covered intellectual life and academic politics, and at the time I was working on a story of my own about the former Yugoslavia. The dissident intellectuals in my piece had followed what seemed the opposite of the Iranian trajectory, from reformist critique within communism to a ferocious and exclusionary nationalism that tore their country apart. Here again was a country after my heart, as I had come to know itone where ideas mattered, and where history was so compressed as to be indistinguishable from the biographies of the people who made it. I was pretty sure my editor at Lingua Franca had read the New Yorker piece, too, when he looked up from editing mine to remark offhandedly that he expected the two of us to reconvene in his office one day to work on a story about Iran.

I started to collect all the scholarly books about Iran that crossed the magazines transom. There would be time, and other subjects, before I got to them, but Iran was the dream story for a writer who loved the things I loved.

I STARTED VISITING I RAN IN 2004. The atmosphere was more oppressive than Id imagined. The excitement over reform had obscured the conditions that rendered such political relaxation so necessary. What I encountered probably would have been familiar to anyone who visited the old Soviet bloc in days gone by, and it was undoubtedly less severe than in many neighboring countries. Still, this was a closed country, and no honest accounting for its politics could fail to acknowledge the fact.

Even ordinary Iranians made the practical assumption that their phones were tapped and e-mails read. Sensitive meetings were best arranged through elaborate chains of in-person contacts. Some of my interview subjects were routinely followed; others received harassing phone calls or were forced to report continually to the men whod interrogated them in prison. A merchant I met in the bazaar slipped me a note to see him privately, which I did, on a busy street corner, where, sotto voce, he explained the layers of political control within his workplace.

Anxiety was a way of life in Iran, and you couldnt report on the country without sharing in it. Iran was not a place where one undertook any kind of opposition, even loyal opposition, lightly. And yet, to my never-ending amazement, this was also a country with a civic spirit that refused to die. The engagement of the Iranian citizenry, against all odds and in the face of pervasive surveillance and often violent repression, suggested lessons for the complacent democracy from which I came.

By the time I started going to Iran, the reformist experiment was apparently over. Many Iranians I met spoke of people like the hostage takers turned reformers and the outgoing President Khatami with bitter disappointment, as vehicles for little more than dashed hopes. I would spend the next ten years and five visits trying to piece together the story of how reform had coalesced, fallen apart, and surged forth as the Green Movement in 2009what it stood for, where it fit into the stream of the countrys consciousness, and what Iran was left with in its wake. This was a story that spanned the revolution itself as well as the three convulsive decades that followed. What Iranians lived in that timewhat they channeled through their intellectual salons and prison letters, their dreams and childhood memoriesfelt to me like an epic novel, replete with calamities and reversals, crescendos and epiphanies, and a sweeping arc of history that cut through its core.

In Tehran in June 2005, I met a young blogger who had recently been released from a harrowing stint in prison. I wrote about Roozbeh Mirebrahimis ordeal with the Iranian justice system in TheNew Yorker that fall. When he arrived on American shores a year later, speaking not a word of English, he came to live with my husband and me until he got settled and his wife, Solmaz Sharif, also a journalist, could join him.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran»

Look at similar books to Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Children of Paradise: The Struggle for the Soul of Iran and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.