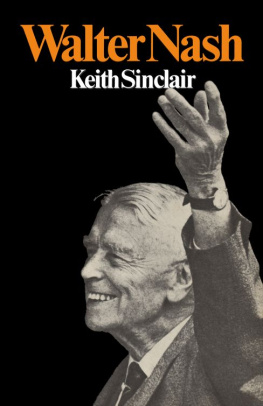

When Sir Walter Nash died in 1968 he left both a study and a very large garage full of the biggest collection of private papers yet known to scholars in New Zealand. The 3,000 or so bundles and boxes of documents, after being purged of newspapers and journals, still weigh several tons and occupy 700 feet of shelves in the National Archives.

I had, three years earlier, asked Sir Walter if I could write his biography. He declined, wishing to sort the papers himself, and hoping to write his own memoirs. After his death, however, his trustees asked me to write his lifenot the life, not an official life, but a life.

I began studying the Nash papers in 1970. In 1971 a generous grant from the Nuffield Foundation, to which I am very greatly indebted, enabled me to employ a research assistant, Mrs Alison Allen, who catalogued the contents of the bundles of papers, and helped my investigations in other ways. Her knowledge of New Zealand Labour history and her good humour made her an ideal assistant and co-worker.

Many people have asked how I could stand reading all these documents, but historians will understand their fascination. No other collection of papers affords a comparable view of New Zealand political history in this century. It includes a very large number of letters from other Labour leaders, including Harry Holland and Micky Savage and Peter Fraser. An extraordinary number of politicians, economists, public servants, academics, parsons, and public figures make their appearances on Nashs stage.

Most of the important episodes in Nashs life are richly and extensively documented in his papers. While he was a cabinet minister he kept his own copies of correspondence relating to any topic he thought significant. Consequently, except in relation to a few topics inadequately covered in his papers, it was not necessary for a biographer to try to follow Sir Walter through the labyrinths of files of the departments which he once headed. However, extensive research was necessary in British archives, chiefly in the Public Record Office, London, to discover the British point of view during Nashs various negotiations with the British government. Some records in the United States, notably the minutes of the Pacific War Council (in the Roosevelt Papers), revealed something of American attitudes towards Nash and New Zealand. In a few cases where it was necessary to seek official New Zealand records, the author was permitted to read them but not to cite his sources. A certain cloudy reticence was in such places necessary.

Nashs papers document, to an extraordinary degree, his personal participation in the life of New Zealand since 1909. The problem which has so often worried the biographer, of how far his book should be a life and times, scarcely arises with the life of someone as continuously active in public events as Nash was. His life was inextricably involved in many of the important events of his time.

If one were writing about a major politician in Great Britain or the USA there would be many published works on the political parties, and on other leaders, as well as the memoirs of the great, for background reading. In New Zealand there are very few such books on modern politicsthere is, for example, no thorough study of any government of this century, nor has any politician of the first rank published his recollections. I have had the good fortune to have some very able research studentsindeed, fellow studentsto carry out parts of the necessary background work. Each year since 1970 several students have spent endless hours Nashing in the National Archives. Mr Bob Hill was, in effect, a collaborator as he worked away at the theology of the guaranteed price. Miss Elizabeth Hanson wrote an excellent account of the political origins of social security. To them, to other students, and to several colleagues who are mentioned in footnotes, I am greatly indebted.

I owe a great deal to Mrs Jane Thomson, who worked as a research assistant, especially in searching the pages of the MaorilandWorker and other newspapers. Mrs Judy Brooker assisted with enquiries into Nashs Anglican connections and Mrs Margaret Thompson by checking references for me. Dr R. M. Dalziel helped with checking references and the bibliography . The Chief Archivists, Miss Judy Hornabrook, and her predecessor, the late John Pascoe, and their staff, were invariably helpful. Many other people assisted in various ways. The sharp editorial eye of Dennis McEldowney saved me from many solecisms and errors. Miss Olive Johnson made the index. Mr Richard Northey was an unfailing source of Labour lore. The late Dr R. M. Campbell and his friend, the late Professor A. G. B. Fisher, took a keen and helpful interest in my work. Mr J. A. D. Nash and Mr L. Nash and other members of Sir Walters family were frank and helpful in answering my queries. The Rt Hon. Harold Macmillan and Sir George Mallaby kindly gave me permission to quote from their published memoirs. Acknowledgements are made to the British Library of Political and Economic Science for permission to quote the Dalton diaries, and to Miss Judy Elphick, who searched them for references to Nash. The University of Auckland gave me leave to visit Great Britain to follow in the footsteps of my subject. I am very grateful to the Advisory Trustees of the Nash estate for making this biography possible.

Professor Roger Louis of Austin, Texas, generously provided a copy of the minutes of the Pacific War Council and other documents from the Roosevelt Papers. Mr John A. Lee kindly gave me access to sections of his papers not open to public. Professor P. J. OFarrell generously gave me a copy of his summary of Labour Party Head Office papers destroyed since he read them.

In the course of studying Nashs life I interviewed the surviving cabinet ministers from the first three Labour ministries and some ministers from the last two, several senior public servants, and former assistants and friends of Nash. Much information and many insights into his personality are derived from their remarks, though these are not always what any one person said. Conflicting opinions might be thought of as triangulating or fixing a position in his personality.

Keith Sinclair

UniversityofAuckland

Contents

AJHR AppendicestotheJournalsoftheHouseofRepresentatives.

N Nash Papers The numbers of bundles and files are prefixed by the letter N: e.g. N1170. Some of these bundles are not yet open to general inspection.

In references to letters etc. Sir Walter Nash is referred to as WN and his wife as Lot.

PD NewZealandParliamentaryDebates.

Reflections of an Elder Statesman Typed notes for a radio interview with Miss Pam Carson of Wellington, in the possession of Mr J. A. D. Nash of Lower Hutt. Miss Carson has a tape.

The Old Country

18821909

Walter Nash was born in England on 12 February 1882, in a small two-storied brick cottage at 93 Mill Street, Kidderminster. Of his ancestors nothing much is known. One of his grandfathers aunts, Sarah Nash, married Francis Lycett, who made a fortune in gloves and was knighted for it. His grandfather died of sickness after returning from the Crimean War, leaving his widow, Margaret, with one baby son, Alfred Arthur. Her son married Amelia Randle who came from the nearby town of Bridgnorth. The young couple lived elsewhere in the town, where three or four of their five sons were born, Ernest, Will, Albert and perhaps Arch, moving to Mill Street in 1880 or 1881.

One of the towns most famous sons, Josiah Mason, who had died in 1881, had been born in the same street, probably on the other side of the road and further up the hill, though Nash always believed that they had been born in the same house. Masons biographer began his book by saying that he was in all respects, a self-made man. He had no advantages of birth, or connexions, or education, or means. So far as regarded the probability of wealth or of personal eminence, no life could have begun in a manner less promising. He made a considerable fortune in Birmingham from split key-rings, steel nibs, and then electroplating, and founded orphanages, almshouses, and a Science College in Birmingham. Its admission policy was to be as liberal as possible, to help poor students. In time Mason College became the building for the University of Birmingham.