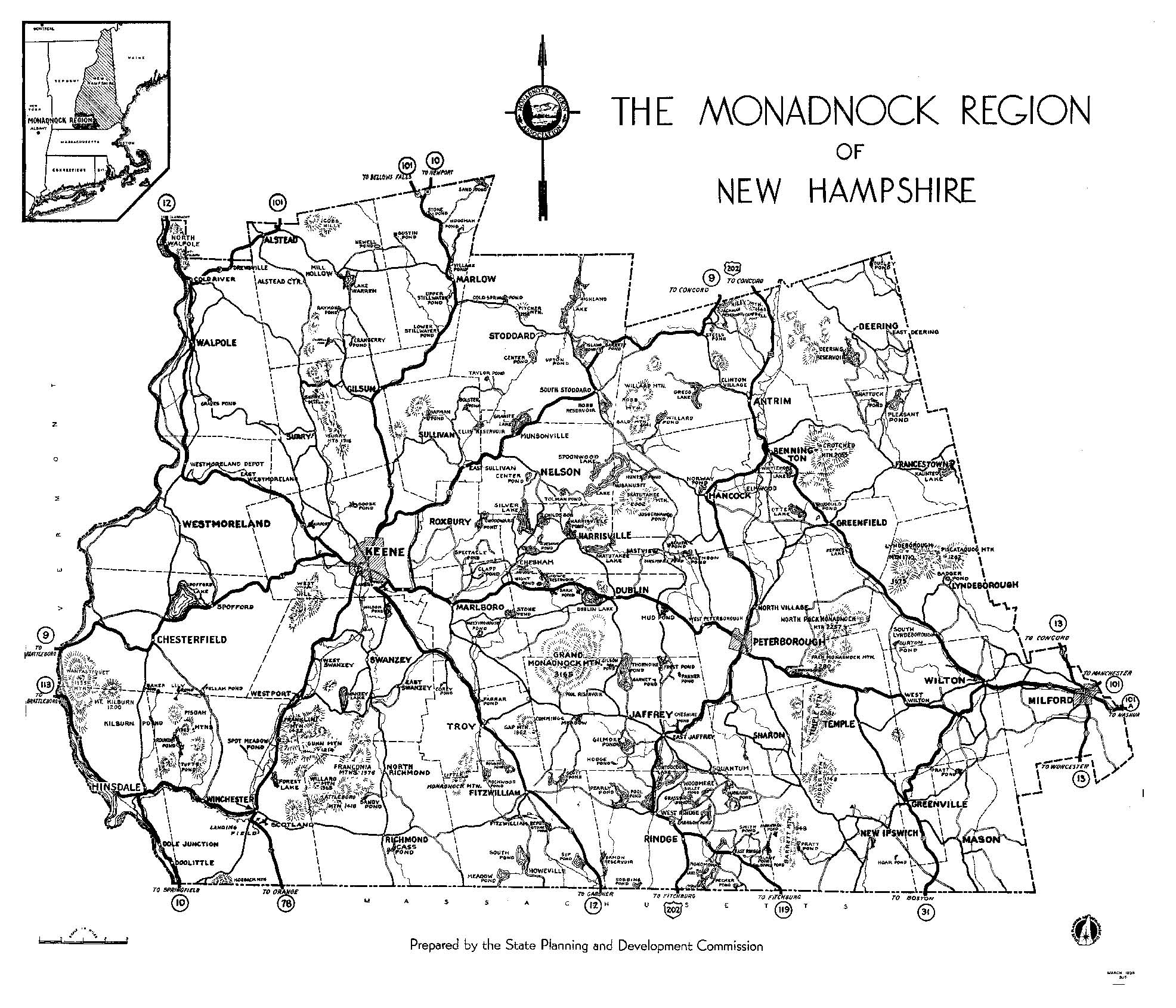

A map of the Monadnock Region prepared in 1936 by the New Hampshire State Planning and Development Commission. (RBS)

Introduction

Every historical society has a collection of old photographs. It may reside in a shoe box in the back of a cupboard, be nicely mounted and labeled in white ink in those black-page scrapbooks orone can only hopebe expertly catalogued, precisely dated, accurately described, profusely documented and permanently protected for posterity in archival quality folders (and, of course, stored at the proper temperature and humidity).

The photographic collections of the local historical societies in the Monadnock region do, indeed, run this gamut. All share, however, at least one quality: they tell us how things were in earlier times. Invariably, the old images Im most drawn to are the ones that pre-date me and are of scenes recognizable today. These are the ones that have lessons to tell. How did a street or a building change over time and was the change for the best?

Anyone who pores through hundreds of stereoscopic views of the 1860s and postcards of the 1930sand everything in betweenquickly realizes that certain themes recur frequently. That they do suggests what was thought noteworthy by our forebears: Mount Monadnock, of course; also the village and its mix of ingredients (the meetinghouse, the common, the post office and store, the inn, Main Street); work and play; public occasions and celebrations; catastrophe and disaster; and the ever-changing means of getting from here to there. The structure of this book simply reflects these recurring themes.

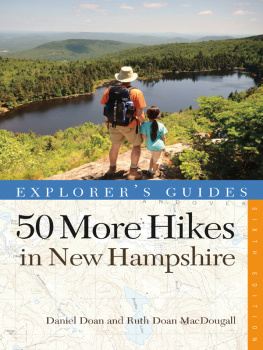

Regions are quite often artificial creations. The Monadnock region really is a region; its residents think of it as a region and refer to it as such. There are certain shared attributes relating to the landscape, history and culture of the area. The most obvious, of course, is the mountain itself, which, even if never climbed or not always noticed, is powerfully ever-present. Count the listings in the phone book if you doubt the spell of Monadnock. But its a region that has indefinite boundaries. It starts at the mountain and works its way outward, but where does it end? Its hard to say (in compiling this book, several more communities might easily have been added and with justification). Being part of a region and sharing certain characteristics does not necessarily mean uniformity, however. The towns of the Monadnock region each have their distinctive identities. There are differences in architecture and townscape, in the types of business and industry, in the interests and lifestyles of the citizens and particularly in such subtle things as character and sense of place. Three good examples are Peterborough, Jaffrey and Rindge; three neighbors, each with about the same number of inhabitants but very different in so many other ways.

For an area so close to the coastal cities of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, the Monadnock region was settled relatively late, in the mid-1700s, long after some areas further inland. In 1736 a township called Rowley Canada was granted by the Great and General Court of the Province of Massachusetts to soldiers or to their descendantswho had served in the Canada expedition of 1690. Most of the sixty-two grantees were from Rowley and neighboring towns, hence the name. When laid out, the township included much of what is now Jaffrey, Rindge and Sharon as well as small portions of Dublin and New Ipswich. Little in the way of permanent settlement resulted. Matters were clouded when the jurisdiction of Massachusetts over Rowley Canada was challenged by twelve prominent New Hampshire men, the majority from Portsmouth, who had purchased the original land grant made in 1620 by King James I to Captain John Mason. Known as the Masonian Proprietors, these twelve operated, according to the custom then, as a speculative land company. Most never saw the townships that resulted, which had the names Monadnock No. 1, No. 2 and so on. Later these future towns were to take on the names we know today: Rindge, Jaffrey, Dublin, Fitzwilliam and Marlborough (and some others as well). Although the dispute was settled in 1748 it didnt, in a sense, make a great deal of difference because virtually no permanent settlement had occurred up to then anyway. But soon things began to happen.

The history of how the region developed starting with the slow trickle of the Scotch-Irish pioneers in the 1750s and continuing through the boom of fleeing urbanites in the 1980s is a long and interesting one; too long to do justice to here. But the old photographs in this book perhaps give some sense of how it all happened, the difficulties encountered and the obstacles overcome.

Robert B. Stephenson

Jaffrey, New Hampshire

Note: The initials in parentheses at the close of each caption indicate the source of the photograph. Refer to the acknowledgments on page 128 for identification.

One

The Mountain

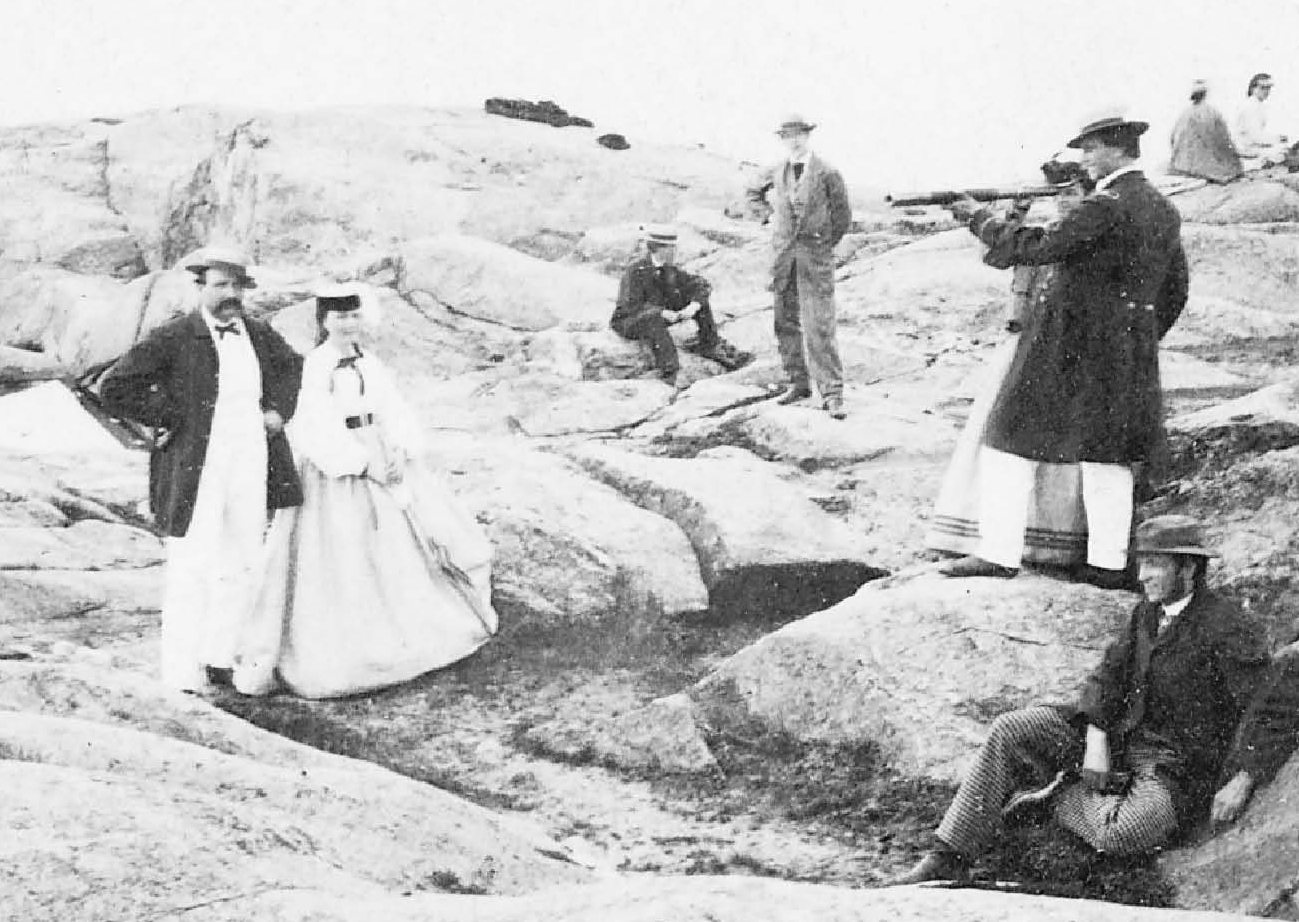

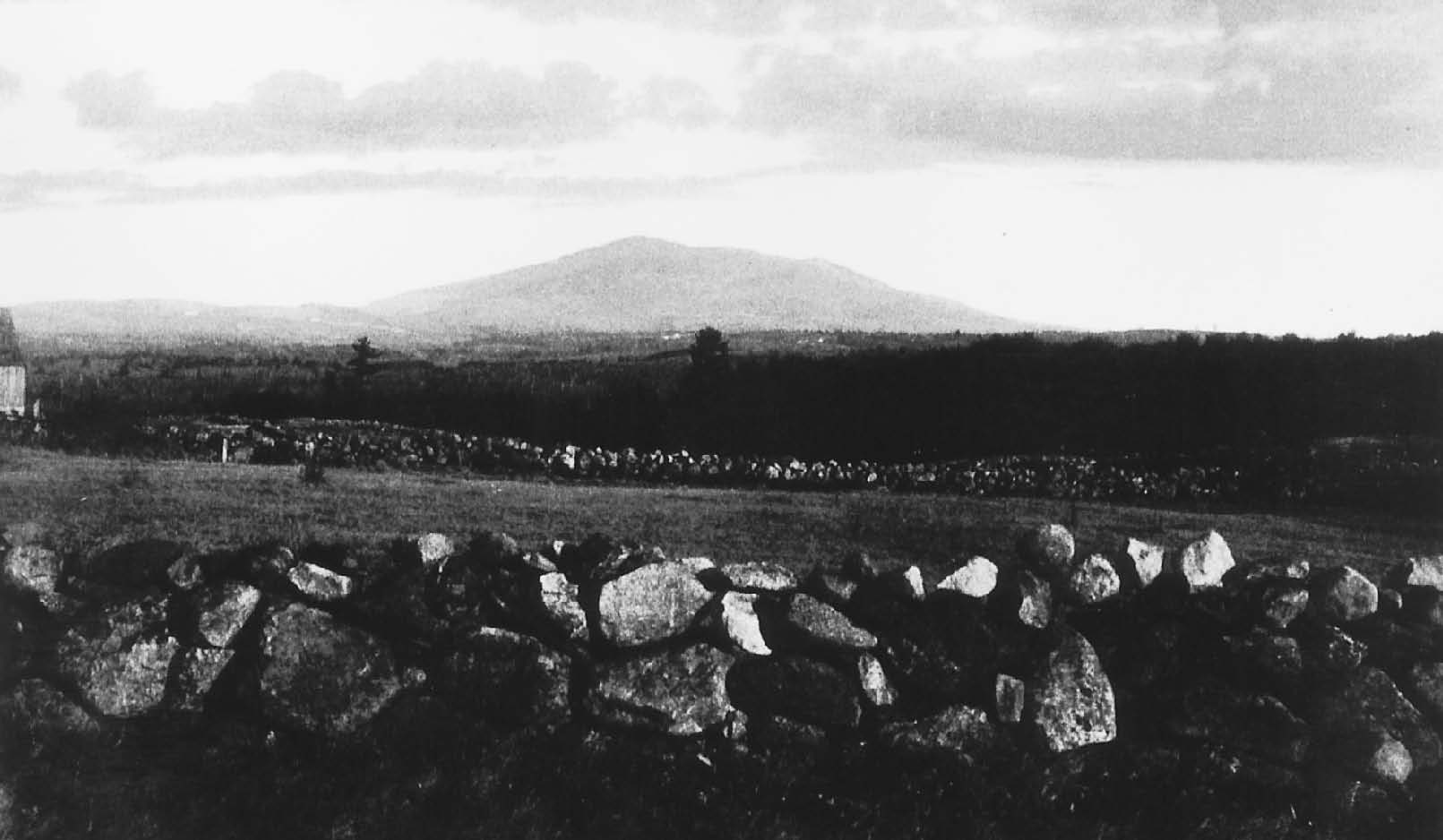

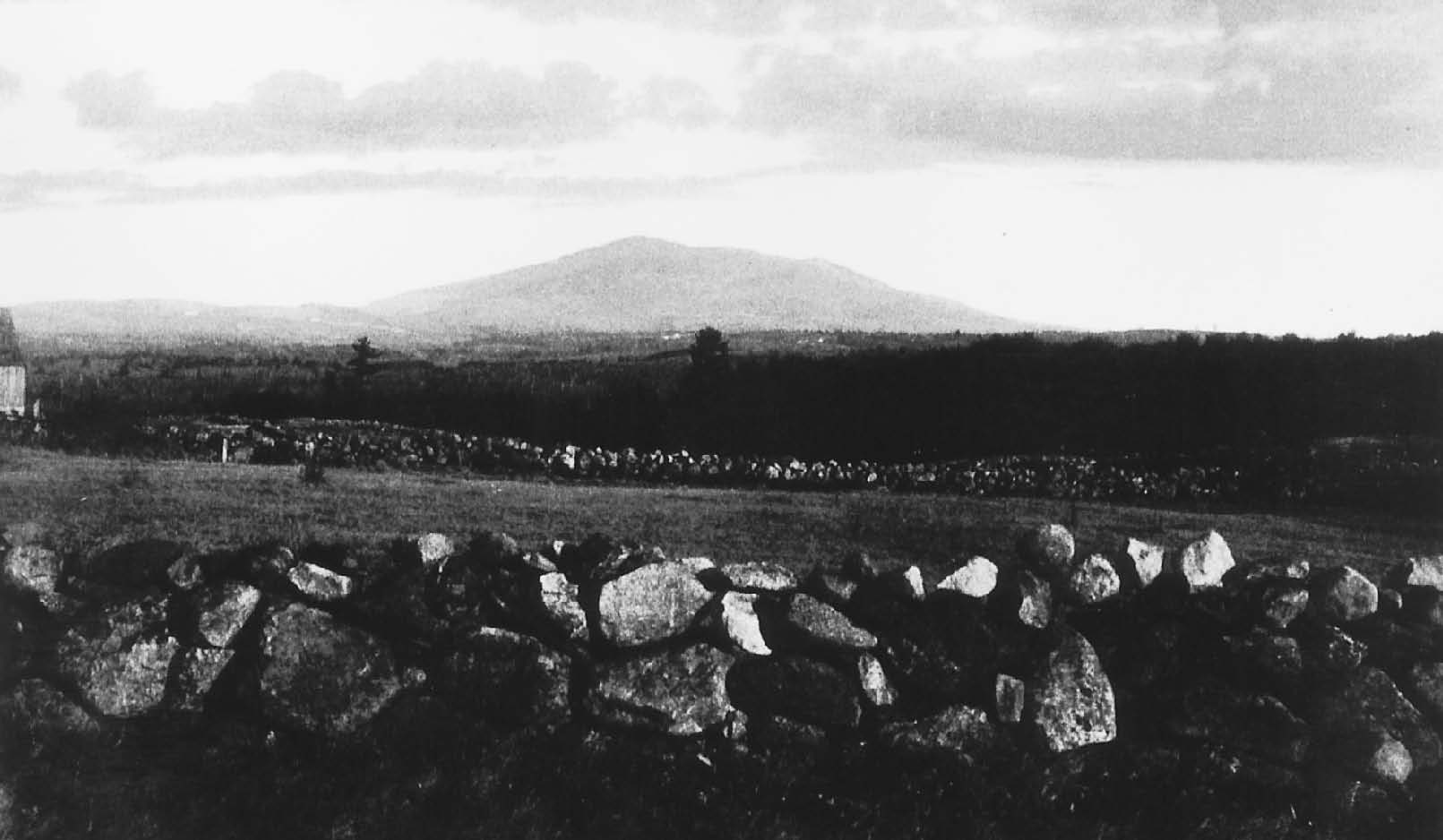

Mount Monadnock is what gives the Monadnock region in southwestern New Hampshire its name. Even before the earliest settlements in the eighteenth century it was a strong physical, spiritual and symbolic presence. The name is Algonquin in origin but there is little agreement about its translation. One source gives it as the place of the unexcelled mountain. Monadnock has many historical and literary associations: Thoreau, Emerson, Twain, Whittier and Kipling all knew the mountain and referred to it in their works. It is, of course, a favorite of hikers, to such an extent that it is considered the most climbed mountain in the world. This view of Monadnock from Perrys Hill in Fitzwilliam is from a time (1898) when the forests had yet to reclaim the fields and meadows of an agricultural age. (FHS)