Table of Contents

Play Time

FILM AND CULTURE SERIES

FILM AND CULTURE

A series of Columbia University Press

Edited by John Belton

For a complete list of titles, see

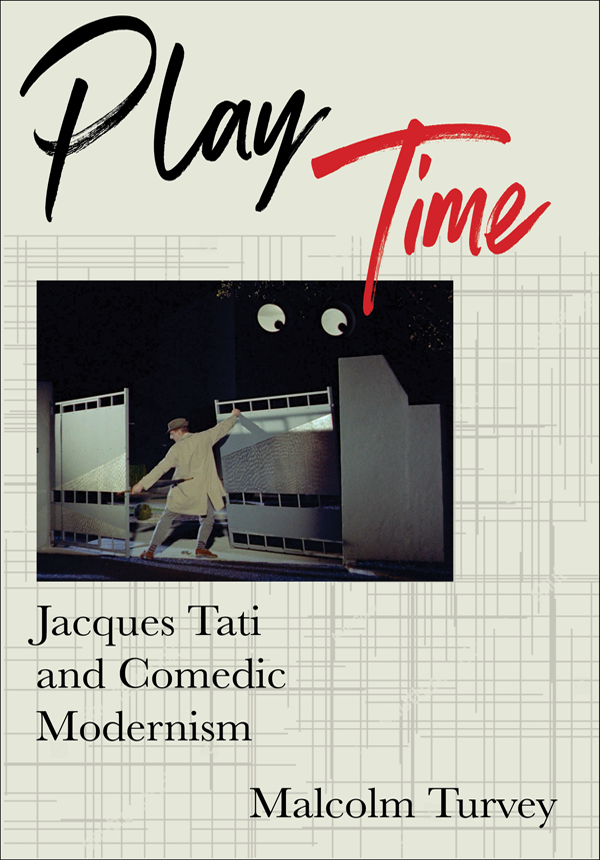

Play Time

Jacques Tati

and Comedic

Modernism

MALCOLM TURVEY

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55011-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Turvey, Malcolm, 1969 author.

Title: Play time: Jacques Tati and comedic modernism / Malcolm Turvey.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2019] | Series: Film and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019013487 | ISBN 9780231193023 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231193030 (paperback: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231550116 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tati, JacquesCriticism and interpretation. | Comedy filmsFrance20th centuryHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.T374 T87 2019 | DDC 791.4302/8092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013487

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER DESIGN: Julia Kushnirsky

COVER IMAGE: Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958)

Les Films de Mon Oncle

Specta Films C.E.P.E.C.

For Will

CONTENTS

W hen I was thirteen years old, my parents took me to see my first Jacques Tati film, Jour de fte (1949). It was the summer of 1982, the year Tati died, and Jour de fte was enjoying one of its many revivals at the recently opened Barbican cinema in the City of London. I wish I could report that I was a precocious teenager who experienced an epiphany while watching the film. Sadly, for the most part, all I remember is being mildly bored by it (although I vividly recall the boy skipping behind the cart of merry-go-round horses as the fair leaves town at the end). I mention my first encounter with Tati not because it made a huge impression on me, but because my parents knew and admired Tatis films enough to want me to see them. Although my father and mother loved the arts and independently pursued music and painting later in life, neither went to university nor received any formal training in arts appreciation. My dad came from a working-class family badly scarred, like so many others, by World War II. He left school at fifteen and took a number of low-wage jobs before completing his national service and working his way into a white-collar profession by attending night school. My mum hailed from a slightly higher class, but only stayed at school until she was sixteen. However, they were lucky enough to come of age in England in the late 1950s, the never-had-it-so-good years of social mobility and prosperity recounted in exhaustive detail in David Kynastons Modernity Britain, and by the time they took me to see Jour de fte, they were firmly middle class, if perhaps on the lower end. In later years they would often fondly reminisce about the jazz clubs they had frequented and the moviesone of which may have been Tatis Mon Oncle (1958), which played in the UK in 1959they had seen when going out in London in their twenties.

Tati is widely revered as one of the most innovative and challenging filmmakers in the history of cinema. In Fifteen Years of French Cinema, Andr Bazins retrospective essay which he first delivered as a lecture in 1957, the great French film critic referred to Tati and Robert Bresson as the two most original, and therefore unclassifiable, talents of postwar French cinema, When I, as a beneficiary of my parents hard work and entry into the middle classes, began learning about the cinema at repertory theaters and then at the University of Kent in my late teens, I would often ask them if they had heard of filmmakers such as Godard, and their answer was invariably no. But Tatis films they knew and loved, and after they died, I discovered a videocassette of Jour de fte among their remaining possessions.

In this book, I try to explain how it was that Tatis films appealed to people like my parentslovers of cinema, to be sure, but not educated cinephiles with any knowledge of elite film culturewhile being almost universally hailed as among the most original and audacious experiments in film construction of the postwar period by critics.. Tatis postwar films therefore continue an already established prewar tradition I call comedic modernism, although Tati inflected this tradition with the distinct concerns of postwar modernism, particularly the desire to democratize art.

The synthesis of modernism and comedian comedy in Tatis films is not the only reason for their widespread appeal. They also vividly express an attitude shared by many toward the rapid modernization that occurred in Western European societies after World War II as a result of renewed prosperity. This is not an antimodern or reactionary attitude, which has often erroneously been ascribed to Tati. Rather, it is much closer to what Alvin Toffler famously called future shock, which he defined as the shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time..

In writing this book, I have been standing on the shoulders of giants. Some of the greatest film critics and scholars have written about Tati, including Bazin, Jean-Luc Godard, Nol Burch, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Roy Armes, Michel Chion, and David Bordwell, and I often draw on their insights in what follows. In particular, I owe a huge debt to Lucy Fischer and Kristin Thompson, who both, in very different ways, have explored the connections between Tatis films and modernism. Fischers dissertation on Tati is one of the best dissertations I have ever read, and it is a great shame it was never published in full. Thompsons articles on Tati, two of which are collected in her essential Breaking the Glass Armor, are indispensable in understanding Tatis style. Even though I disagree with them sometimes, I would not have been able to write this book without their pioneering work. The same is true of Nol Carrolls groundbreaking article Notes on the Sight Gag, to which I repeatedly turn in the pages that follow. It is a clich that comedy is hard to analyze, but Carrolls article incisively identifies and elucidates the gag structures in classical comedian comedy. I use it to show that Tati drew on these structures while modifying, radicalizing, and adding to them in pursuit of his modernist goals. It is also a clich that, in analyzing comedy, one inevitably destroys it. I have never found this to be true, and it certainly isnt the case with Tati, at least for me. My deep dive into his comic style has only increased my appreciation for the enormity of his comic achievement, and my sincerest hope is that readers will come to share this appreciation.

This book originated in a paper I delivered at the annual conference of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image (SCSMI) in 2010. The enthusiastic response from audience members, especially David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, encouraged me to develop the paper into a book-length project. Although I consider myself more of a fellow traveler than card-carrying member of SCSMI, the society has been the closest thing I have to an intellectual home for twenty years, and I am grateful for the friends I have made through it, particularly Johannes Riis.