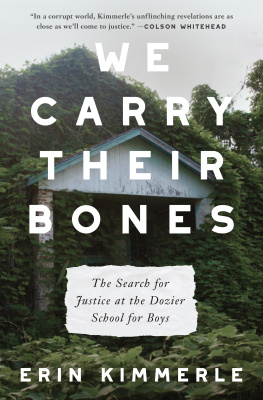

This book was written to honor and support all who suffered at the Dozier School for Boys, including those who came forth to tell their stories and those who could not. It is my hope that in relating the accounts of the men of Dozier, I can help convey the power of abuse and the power of truth telling. Although reading the heartbreaking accounts of the Dozier survivors is difficult, it was an honor to write this story and promote their cause. I hope they someday find peace and justice. I also dedicate this book to my grandson, Sam; may he grow to be wise and strong and work to promote justice and healing.

My sincere appreciation goes to my four-time editor, Domenica Di Piazza. She sure has a way with my words! I am also grateful to all the fellow authors who have written about Dozier, from the survivors to the journalists, especially Carol Marbin Miller, who took the lead from the outset and made things happen.

Text copyright 2020 by Elizabeth A. Murray

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Twenty-First Century Books

An imprint of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

Main body text set in Adobe Garamond Pro Regular.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for The Dozier School for Boys: Forensics, Survivors, and a Painful Past is on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-5415-1978-7 (lib. bdg.)

ISBN 978-1-5415-6269-1 (eb pdf)

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-44314-34560-2/25/2019

Contents

Chapter 1

Reforming Wayward Youth

Chapter 2

Sunup to Sundown

Chapter 3

The White House

Chapter 4

We Were Just Kids

Chapter 5

Making Themselves Heard

Chapter 6

Closed without Closure

Chapter 7

Digging for the Truth

Chapter 8

The Bones Still Cry Out

Chapter 1

Reforming Wayward Youth

T he fire began on the ground floor of the Florida State Reform School dormitory in the early hours of the morning. When the fire was first discovered at three thirty, about one hundred boys and several employees were asleep in their beds on the third floor of the building. When the night watchmans calls awakened them, they realized they were trapped. The upstairs fire escape doors were locked, and flames blocked the main stairway. The buildings wooden floors had recently been painted with oil-based paint and were burning rapidly. The residents scrambled frantically to get out. Many ran to an alternate stairwell and escaped. Others were not so fortunate. One boy and two employees near the fire escape fell to their deaths through the collapsing floor. Others died elsewhere in the building, most likely from smoke inhalation. The dormitory burned completely to the ground. The charred remains of several bodies were recovered from the fires residue and were buried in Boot Hill, the school cemetery. The cause of the fire and the number of dead were never confirmed and are still debated.

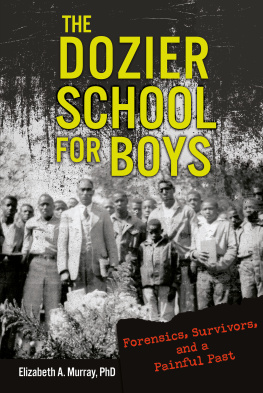

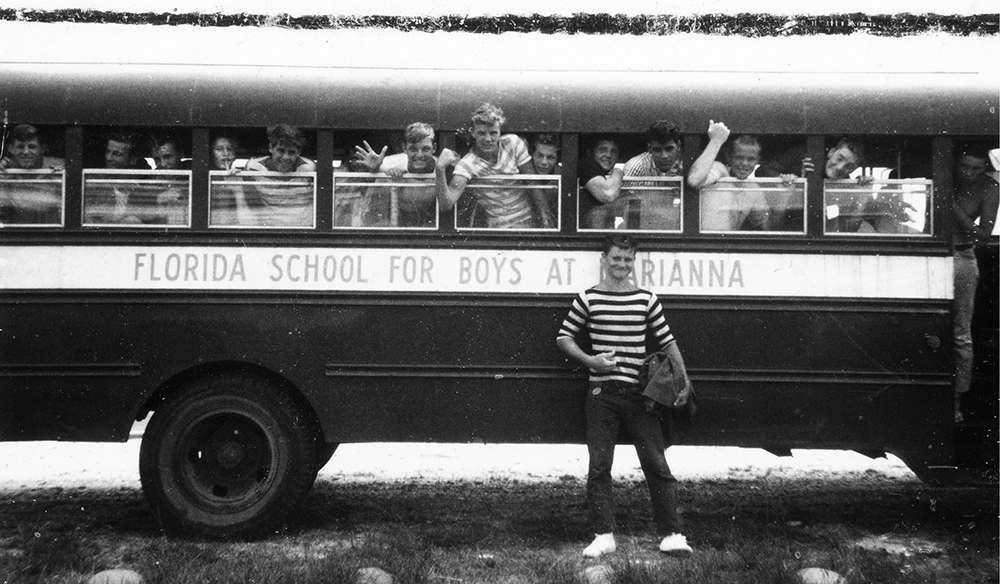

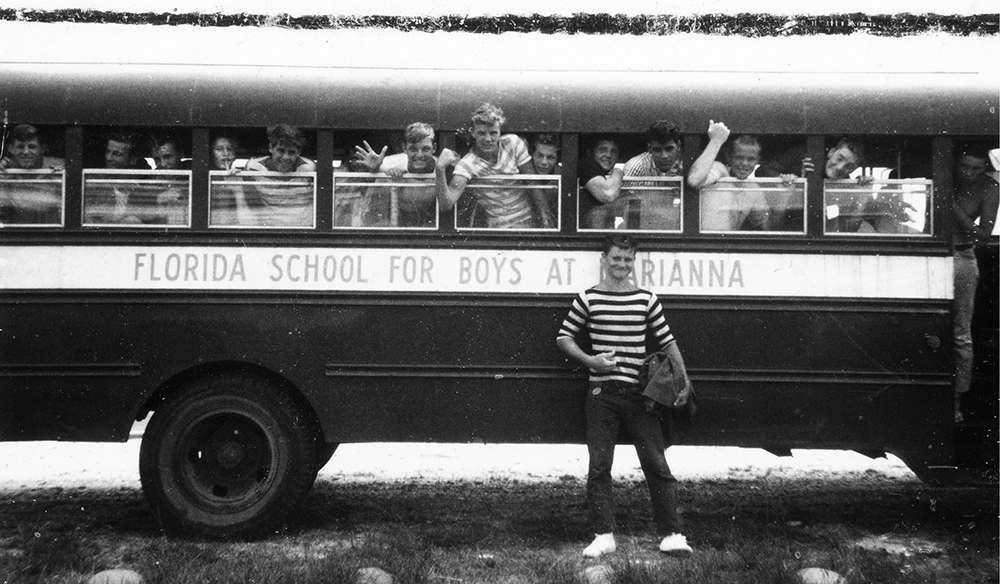

The Dozier School was founded to house troubled and lawbreaking youth. Its goals were to help them learn skills and build character before being released back into society. From the outside, the school appeared to be a cheerful environment, as in this 1957 photo of boys arriving at Dozier by bus. But the school held dark secrets of abuse and suffering.

Character Fitting for a Good Citizen

The Florida State Reform School was a juvenile incarceration center established by Florida law in 1897. Located near the town of Marianna in Jackson County, the schools mission was to be an institution that was not simply a place of correction, but a reform school, where the young offender of the law, separated from vicious associates, may receive careful physical, intellectual, and moral training, be reformed and restored to the community with purposes and character fitting for a good citizen, an honorable and honest man, with a trade or skilled occupation fitting such person for self-maintenance.

By 1914, the year of the fire at the school, the United States was a prosperous nation. The Industrial Revolution of the previous century had brought machine-based manufacturing to Europe and the United States. The new technologies were mechanized and powered by steam-based, coal-powered engines. Transportation, communication, and farming industries no longer solely relied on animal and human hand labor. They were becoming more reliant on machines built by workers in factories.

Thousands of Americans migrated to cities, hoping for jobs in the factories. But instead of prosperity, many found poverty and despair. Without labor laws to protect them, children worked twelve- to sixteen-hour shifts in factories for only one or two dollars a day. And because they were small, children also worked in narrow, underground mine shafts, digging up coal to power the engines of steam locomotives and factories, and to heat homes and other buildings. Women, too, worked long hours in factories for little pay. Men often worked into old age because Social Security and other financial support for retirement did not yet exist. Nonetheless, most Americans believed that a strong work ethic was the key to success. They held to an old saying that idle hands are the devils workshop.

At this same time in US history, ideas about education, criminal justice, and civil rights were shifting. New theories in the fields of psychology and sociology were beginning to influence family life and public institutions, including the legal system. Reformatory schools came out of these new ideas. The schools were places to house juvenile offenders. Before this time, juveniles and adult criminals served their sentences together. At the reform schools, youth would receive an education and training in the technological skills needed for the new manufacturing era. Also known as industrial schools, reformatory schools began to emerge throughout the United States to house and reform delinquent children.

Establishing Order

The Florida State Reform School opened its doors on January 1, 1900. It was originally set on 1,200 acres (486 ha) in northwestern Florida and later grew to 1,400 acres (567 ha). At one point, it was the largest reform school for youth in the United Statestoo large to be fenced in. The schools original main building was beautiful and white. It sat on a hill, nestled in farmland and approached by a lovely tree-lined road. Workers put up additional buildings over time, including dormitories and dining facilities.

According to the law, residents of the schools were to be boys and girls under the age of sixteen who had been convicted of crimes, either felonies or misdemeanors (less serious wrongdoings). The children could be sentenced to the reformatory for not less than six months and not more than four years. In addition, any court in Florida could commit children who were incorrigible (uncontrollable) or who engaged in vicious conduct to the school for guardianship, as long as they were between the ages of ten and sixteen.