Erin Kimmerle - We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys

Here you can read online Erin Kimmerle - We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Erin Kimmerle: author's other books

Who wrote We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Know you what it is to be a child?

It is to be something very different from the man of today. It is to have a spirit yet streaming from the waters of baptism; it is to believe in love, to believe in loveliness, to believe in belief; it is to be so little that the elves can reach to whisper in your ear; it is to turn pumpkins into coaches, and mice into horses, lowness into loftiness, and nothing into everything, for each child has its fairy godmother in its soul; it is to live in a nutshell and to count yourself the king of infinite space; it is

To see a world in a grain of sand,

And a Heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour;

it is to know not as yet that you are under sentence of life, nor petition that it be commuted into death.

FRANCIS THOMPSON

This book is for my children,

Sean and Reid

T he Florida State Reform School opened January 1, 1900, and closed in 2011, under the name Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys. From its inception, it was supposed to be a school, not a prison. Although all children committed were supposed to have been convicted of a crime and sentenced by a judge, the laws were later amended to include non-criminal offenses such as truancy and incorrigibility, leading it to become the largest reform school in the country and obscuring the line between student and inmate. Until 1968, the reform school segregated into two completely separate campuses, or departments, for white and colored persons. Colored meant anyone deemed non-white.

Throughout this book, the terms white and colored are used when necessary, according to the historical records and documentation. Attendance ledgers showed that for many boys who had mixed ancestry or Latino backgrounds, administrators were uncertain where to place them and, at times, transferred boys between the two departments. This occurred because race is a social construction with no biological association that uniquely identifies one race at the exclusion of all others. The classification system used during the Jim Crow era affected the availability of written records, documentation, and associated burial information. Vital records such as birth and death certificates were less commonly given to people of color.

B efore the lawsuits and protests, before the ground-penetrating radar and DNA testing, before we were stalked and before the citizens of Jackson County tried to have me arrested, before we ever stuck a shovel in the red dirt of North Florida to exhume bodies, I stood in the womens restroom as the news media gathered in the large room outside and began setting up their cameras and checking their microphones and waiting for me to step before them and tell them what I had learned about the dead boys.

I did not want to do this.

I had spoken at a single press conference prior, years before, near a crime scene where I had been helping the local sheriff excavate the remains of a woman missing for ten years. The sheriffs office wanted me to give the press briefing, to deflect questions about the open homicide investigation toward the science of forensic anthropology. To tell the public what we were doing without saying anything about what we were doing. I can steel myself against unimaginable horrors, given my job, but reporters mean putting it all out there. I prefer to fly under the radar.

Im a forensic anthropologist, a scientist, an academic. Im not a showman. I strive for accuracy, and sometimes forensic science takes a lot of explaining. I dont think in sound bites. A peer-reviewed and long-winded scientific explanation is not what the television news reporters want, though. They want short, chippy, quotable sentences with strong verbs and hard nouns. They want the coach jogging off the field at halftime, summarizing the play so far and the strategy for the second half.

Here, now, I struggled with how to reduce a year of scientific investigation into a few punchy paragraphs to lead the nightly newscasts. They wanted me to address the mounting controversy around the clandestine cemetery on the property of the Dozier School for Boys, Floridas oldest state-run reform school, in the rural panhandle town of Marianna, where we had been searching for the truth. That meant Id spend the next day answering tough questions and trying to soothe hurt feelings. Not from reporters, though. From politicians, Marianna residents, university administrators, fellow academics, and lawyers. Facing the press, as scary as it was, would be the easy part.

I looked at myself in the mirror.

I paced.

I twirled my fingers on both hands two at a time in small circles, an old high school theater trick to help me focus. Thumbs first. Then forefingers. Then the middles, rings, pinkies.

Over and over.

Ten times each.

I thought about how clean and gorgeous this bathroom was, with its granite walls extended to the ceilings. The bathroom cost more than our forensic anthropology labs entire operating budget, and its beauty stood in such contrast to how I spent most of the past year, covered in mud and dirt.

The door swung open, and Lara Wade, the University of South Floridas director of media relations, entered. She asked me if I was hiding and laughed. I just smiled and then reached out and put the palms of my hands on the granite wall. It felt so cold.

This was her idea, putting us in front of the television cameras. Id invited two fellow faculty members to join our team, and they were gathering outside as well: Dr. Antoinette Jackson, a cultural anthropologist, and Dr. Christian Wells, an archaeologist. What was supposed to be two weeks of fieldwork for us and a few students had turned into a year of probing and research involving a growing group of experts across disciplines.

Lara knew the value. This would be a big boost in earned media exposure for my department and the university. She knew how important it was to keep the ball rolling. If we wanted to help the families, we had to be out front.

Lara had a calming effect; I trusted her. She started running through the details and rattling off a list of all the dignitaries gathered outside. She knew every reporter by name.

Then she stopped and looked at me in the mirror.

You have five minutes, she said. You got this.

I thought about what brought me to this moment, the rising tension from multiple sides. It all started simply enough: a friend had introduced me to a local reporter whod been working on a series of stories about the reform schools dark history, about brutal beatings and sadistic guards and mysterious deaths.

The stories raised questions about a purported cemetery on the schools property, and the reporter had hit a dead end. He had found the families of boys who died in custody and were buried at the school, families that had never found peace, for theyd never been given the opportunity to properly mourn. No one could point to the location of the graves where their brothers and uncles were buried. No state official had stepped up to find those burials.

This was my lifes work. Not a lot of people have this particular skill set, to find and identify the dead. It was easy enough to secure permission to go take a look around. Back then, in early 2012, that was essentially the scope of the project. To learn what I could about the deaths at a reform school that had been in operation for more than a hundred years on the edge of a warm and friendly Southern town. How hard could it be?

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection controlled half of the fourteen-hundred-acre reform school property, the half that had been the colored side until racial integration in the late 1960s. Thats where the old burial ground was located. The DEP gave us permission to document and research the historic site.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

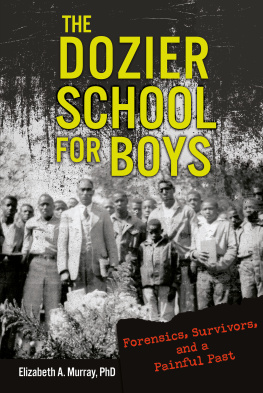

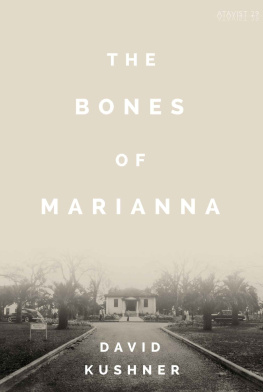

Similar books «We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys»

Look at similar books to We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book We Carry Their Bones: The Search for Justice at the Dozier School for Boys and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.