This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781407097329

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Arrow in 2006

Copyright Tom Harper 2005

Tom Harper has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the products of the authors imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Century

The Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be

found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099454762

The Random House Group Limited makes every effort to ensure that the papers used in its books are made from trees that have been legally sourced from well-managed and credibly certified forests. Our paper procurement policy can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/paper.htm

Typeset in Minion by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Polmont, Stirlingshire

Printed in the UK by CPI Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

About the Author

Tom Harper is also the author of The Mosaic of Shadows and Siege of Heaven.

He studied medieval history at Oxford University and now lives in London.

Visit Tom Harper at www.tom-harper.co.uk

For my parents

who gave me afterward every day

For lo I raise up that bitter and hasty nation,

Which march through the breadth of the earth

To possess the dwelling places that are not theirs.

They are terrible and dreadful,

Their judgement and their dignity proceed from themselves.

Their horses are swifter than leopards,

And are more fierce than the evening wolves.

Their horsemen spread themselves, yea,

Their horsemen come from afar.

They fly as an eagle that hasteth to devour,

They come all of them for violence;

Their faces are set as the east wind,

And they gather captives as the sand.

Habakkuk

(adapted C. V. Stanford)

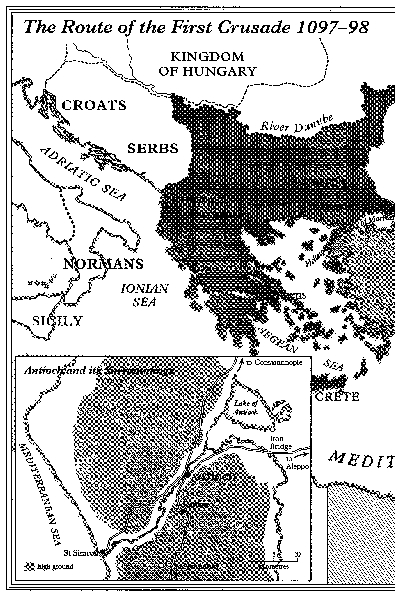

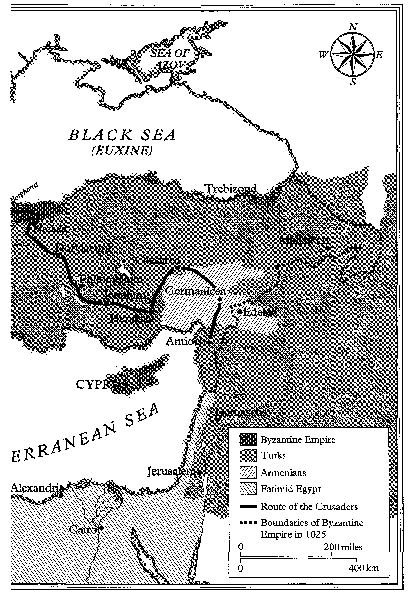

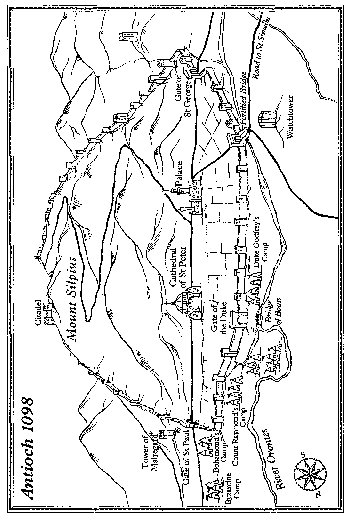

Having sworn allegiance to Byzantium, the army of the First Crusade crossed into Asia Minor in May 1097. At Nicaea and Dorylaeum they won two resounding victories against the Turks, capturing their capital and opening the road south towards Jerusalem. Through July and August, in the face of burning heat and hunger, the crusaders swept aside all resistance as they marched almost a thousand miles across the steppes of Anatolia. Outside the ancient city of Antioch, however, their progress halted: the Turkish garrison was all but impregnable, and as winter drew on the army was devastated by rain, disease, starvation and battle. By February 1098 they had suffered five months of attrition to no discernible gain. Rivalries festered between the different nations of the crusade Provencales from southern France, Germans from Lorraine, Normans from Sicily and Normandy, and Byzantine Greeks. Fractious princes grew jealous of each others ambitions, while the miserable mass of foot-soldiers and camp-followers seethed at the failure of their leaders to deliver them. And in the east, the Turks began to assemble an army that would crush the crusade once and for all against the walls of Antioch.

KNIGHTSOFTHE CROSSTom Harper

Historical Note

The battle for Antioch is perhaps best understood as the Stalingrad of the First Crusade. In both cases, invading armies made rapid progress across enemy territory before becoming mired for months outside cities too large and tenaciously defended to be taken. In both cases, the besiegers were then themselves surrounded, with the crucial difference that the crusaders were eventually able to break out and raise the siege. Had they failed, Pope Urbans vision of conquest would have foundered as surely as did Hitlers in 1942. It is hardly surprising, then, to discover the catalogue of greed, intrigue, treachery and extraordinary violence that attended the siege. In general facts and chronology, as well as in the characters of the leaders, I have tried to be as faithful as possible to the (often contradictory) sources. The privations that the army suffered, the sudden taking of the city two days before Kerbogha arrived, the finding of the Holy Lance, and the extraordinary victory against overwhelming odds in the final battle, all happened much as I have described. Contemporary chroniclers could find no explanation other than the miraculous, and modern historians offer few more solid answers.

The one area where I have taken substantial liberties with history is in the matter of the heretics. The sources make no reference to the appearance of heresy among the crusaders as you would expect from a group of clerical chroniclers glorifying the papacys great achievement but we know that the crusaders did encounter local heretics en route. There was a strong puritanical element among the mass of non-combatants, and it frequently voiced itself in opposition to the decadence of their leaders. Given how disastrously awry those leaders seemed to have led the crusade during the terrible winter of 109798, and how impossible it was to disentangle the spiritual and political spheres in the medieval mind, it seems entirely plausible that social protest would naturally have led some pilgrims to more radical theologies. In a group of exceptional piety, enduring extraordinary suffering and finding themselves beyond all bounds of their known world, it seems reasonable to suppose that some would have looked beyond the confines of orthodoxy for relief particularly in the spawning ground of faiths that was and is the Middle East. The heterodox beliefs I describe are based on ideas that were both contemporary and enduring, but are not meant to reflect the precise tenets of any particular sects.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

In trying to make sense of the tangled history of the First Crusade, I have relied principally on the judgements of two clear-thinking historians: Steven Runcimans A History of the Crusades (Penguin) and John Frances