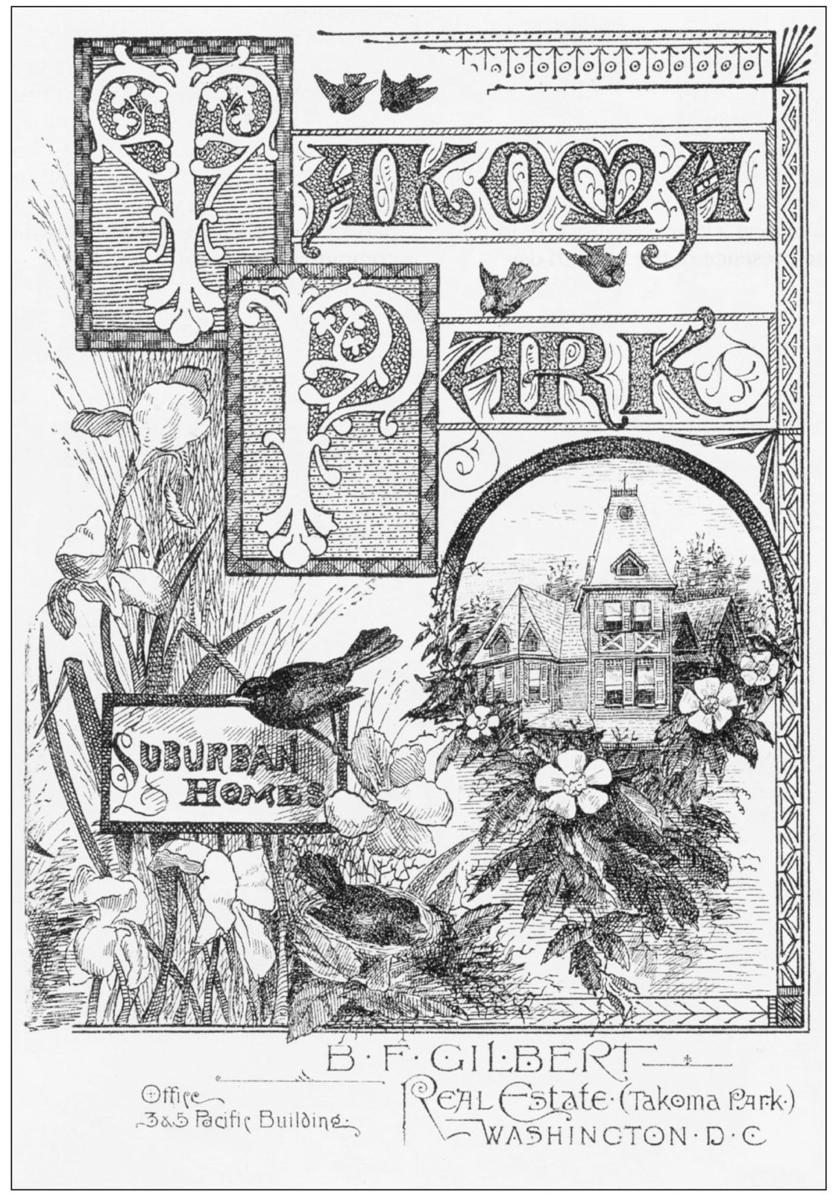

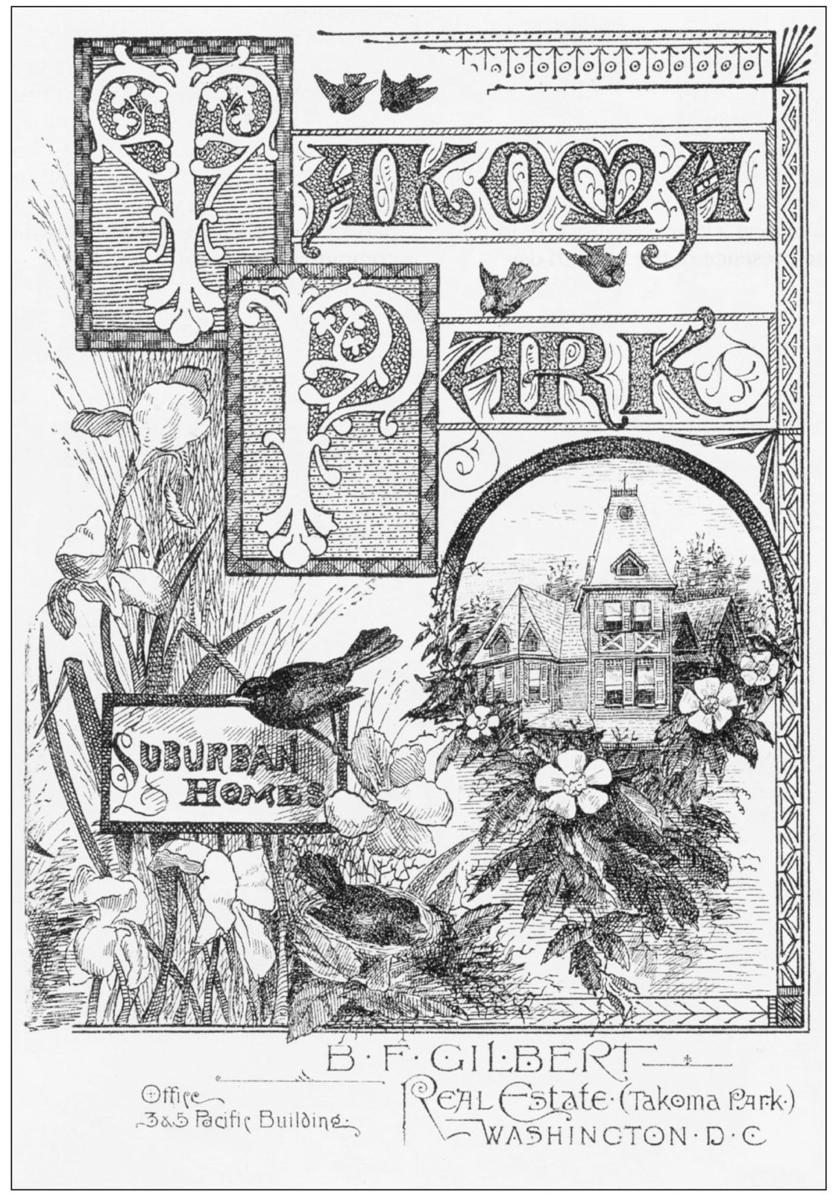

This artwork graced the cover of the 1888 marketing brochure created by Benjamin Franklin Gilbert to attract new residents to the sylvan suburb he founded on the railroad line north of Washington, DC. The house pictured here was Gilberts own residence, lost to fire in 1915. Today, this graphic remains the iconic image of early Takoma. (Courtesy of Historic Takoma.)

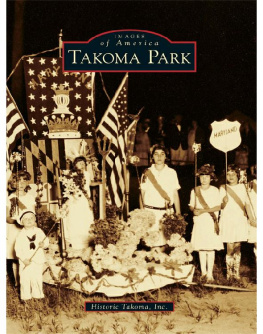

ON THE COVER: Takoma Parks most enduring tradition is its annual Independence Day celebration. As this color guard float from the 1920s illustrates, children have played a prominent role in the parades since the early days. (Courtesy of Historic Takoma.)

Takoma Park

Historic Takoma, Inc.

Copyright 2011 by Historic Takoma, Inc.

9781439641453

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010924654

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail sales@arcadiapublishing.com

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

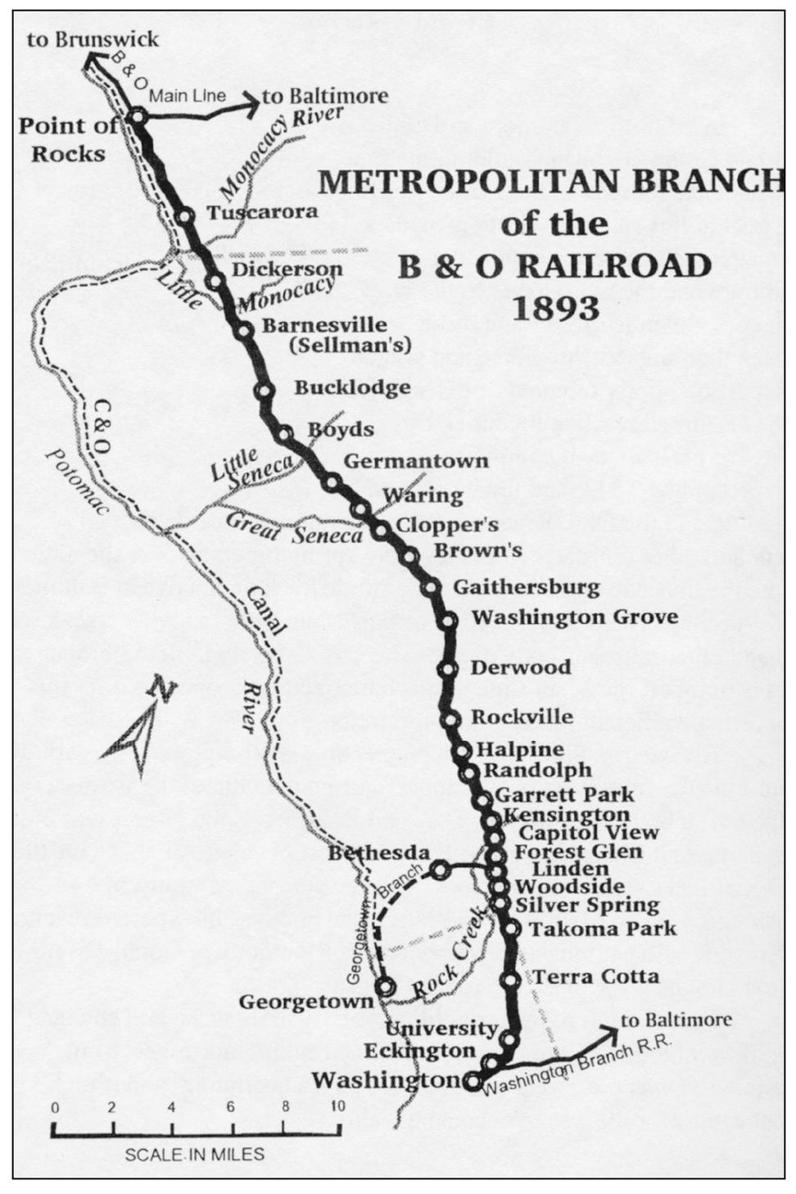

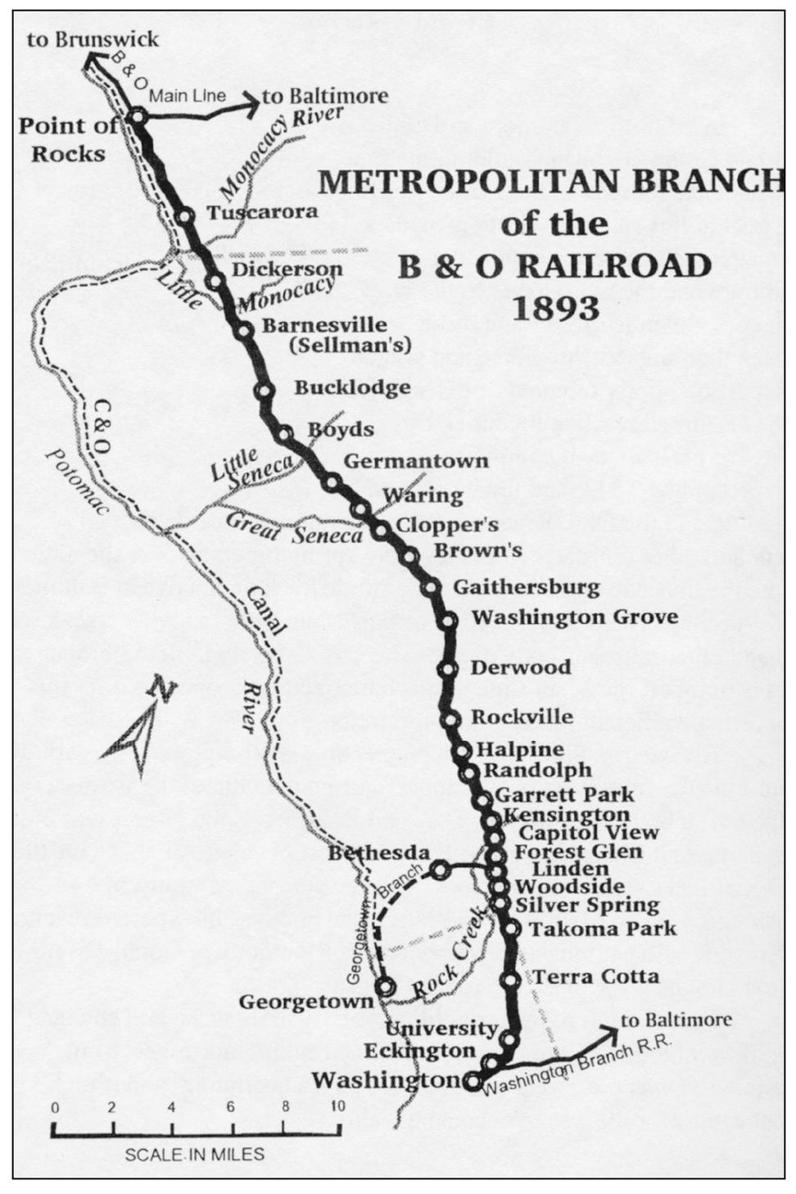

The 1873 opening of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Metropolitan line gave Gilbert an opportunity to create a new community where downtown workers could enjoy the benefits of country living. The new line stretched from the heart of Washington, DC, north to Point of Rocks near the West Virginia border. Gilbert chose the point where the railroad tracks crossed into Maryland as the site for Takoma Park. Many of the names on this 1893 station map are familiar as Metro stops today. (Map from The Met: A History of the Metropolitan Branch of the B&O Railroad by Susan Soderberg, published by the Germantown Historical Society.)

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book celebrates B.F. Gilberts vision and the many individuals who have sustained it over the years. We thankfully acknowledge the early historians and chroniclers whose legacies enrich this record: Dr. William Hooker, Charles Heaton, Frank Skinner, and John Coffman, as well as photographers Morris Bien and Arthur Colburn.

We are also grateful to the numerous archivists whose generous assistance enabled us to include material from important public and private collections, especially Faye Haskins (Washingtoniana Division of the Martin Luther King Library of the District of Columbia), Tim Poirier (Ellen G. White Estate Archives), Greg Gohlke (Review and Herald Publishing Association Archives), Lydia Parris (Washington Adventist Hospital), Lee Wisel (Washington Adventist University), Maureen Feely (Bliss Electrical School), Donna Guiffre (Montgomery Blair High School Archives), Angela Todd (Hunt Institute, Carnegie-Mellon University), Steve Whitney (Coolidge High School Alumni Association), and Richard Singer (Herald and Review Collection).

In addition, we salute the willingness of local residents to share their personal and family photographs, including Nancy Abbott-Young, Lois Chalmers, Karen Collins, Kay Daniels-Cohen, Dolly Davis, Cathy Fink and Marty Marxer, Robert Ginsberg, Tina Hudak, James Jarboe, Kathie Mack, Patricia Matthews, Chris Simpson, Jeanne Skinner, Saul Schniderman, and Bruce Williams. Eric Bond and Julie Wiatt of the Takoma Voice also deserve a special nod, along with David Lanar of Boy Scout Troop 33 and Jo Hoge of the Takoma Park Presbyterian Church.

We are especially indebted to the work of Ellen Marsh and Mary Ann OBoyle, coauthors of the 1983 centennial history Portrait of a Victorian Suburb , and to archivists Karen Fishman and Ann Juneau for organizing the Historic Takoma collection.

This book has been a complicated project as we sought to gather photographs and to document previously untold stories and shed new light on old ones. We thank our Arcadia production team for their patience. We are grateful to Brian McGuire for his copyediting skills. Finally, we dedicate this effort, with esteem and affection, to Dorothy Thomson Barnes, Historic Takomas resident historian, indispensable fact-checker, and on-the-scene observer since 1922.

Diana Kohn, Caroline Alderson, and Susan P. Schreiber,

on behalf of Historic Takoma

info@historictakoma.org

INTRODUCTION

The land that became Takoma Park lies six miles north of the Washington Monument. Even after the Civil War, the capital city proper had not yet reached beyond Florida Avenue, and much of the woods and farmland to the north was still in the hands of the old colonial families who had established plantation-sized holdings.

When Confederate general Jubal Early advanced on Washington in July 1864, his troops marched through the future Takoma Park and adjacent Silver Spring (the compound of the Blair family). The two-day Battle of Fort Stevens, which just barely succeeded in deterring the Confederates from capturing the Union capital, was fought in the backyard of our future suburb.

The Union emerged from the war victorious, and in the heady days that followed, Washington continued the expansion begun in wartime. Speculators came to make quick money, artisans to work on large building projects, and young men were eager to fill government clerk posts. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company opened the Metropolitan Line in 1873, linking the federal city with points north and setting the stage for the creation of suburbs like Takoma Park.

Developer Benjamin Franklin Gilbert was not the only one who saw the opportunity to create towns at the train stops, but he was the first to act on it. The land he purchased in 1883 lay on the boundary line between the District and Maryland.

A gifted promoter, Gilbert rapidly gathered energetic and forward-looking settlers ready to carve a community out of the woods. Within a year, there were five finished houses, and by 1888, there were 1,000 residents. By the time the town was incorporated in 1890, there was a prominent train station, a school, a church, and an Independence Day celebration on its way to becoming a tradition. Although only the Maryland side became the town of Takoma Park, for the most part, the community ignored the boundary line as the town developed.

The optimism of the boom years was tempered by financial panics that constrained Gilberts ambitions, but the town continued to attract new residents. Most notable were the Seventh-day Adventists, who arrived in 1904. Within a decade, the Adventist world headquarters, publishing house, hospital, and college were dominant features on the landscape, with Adventists constituting almost a third of Takoma Parks population. Among the residents were a small number of African American families whose occupancy predated Gilberts subdivisions.

The addition of two trolley lines expanded the options for Takoma Parks early rail commuters. A healthy commercial district evolved around these connections and substantially survives to the present day. For a time, Takoma Park was the largest town in Montgomery County.

From its inception, B.F. Gilbert encouraged citizens to contribute and come together to address community issues. This can-do attitude fostered Takoma Parks political and social activism and also, perhaps, its reputation as one of the most vibrant and progressive communities in the area of metropolitan Washington, DC.

In the early decades of the 20th century, residents took an active hand in organizing their community life. An array of clubs appeared, including early scout troops, a volunteer fire department, a library, and additional churches. As local young men marched off to World War II, residents opened their homes to an influx of wartime workers, such as nurses at Walter Reed Hospital, just across Georgia Avenue, and government girls who came to Washington to work in wartime government agencies. Residents planted victory gardens, kept watch for enemy planes, and installed blackout curtains.

Next page