ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks firstly to Neil Hanson, my co-writer, without whose full commitment and skills this book would never have been written. Likewise to Mark Lucas, our literary agent and The Soho Agency, and to Ian Marshall, Frances Jessop, Kerri Sharp and the rest of the brilliant team at Simon & Schuster for their skill, enthusiasm and whole-hearted commitment to the story. Thanks also to my wonderful parents, Gerald and Rosemary Anderson, my fabulous siblings Bridget, Anthony and Stephen, and my civil partner, Jon Turner, all of whom have encouraged me in never giving up on this project.

In researching and writing this account of the trial of Andrei Andrusha Sawoniuk, we have been helped by numerous individuals and organisations who gave unstintingly of their time and knowledge. My good friends John Kelsey-Fry QC and Russell Jacobs were unfailing sources of support and wise advice, and Russells sister, Beverley, provided expert translations of Hebrew documents. Were grateful also to Shulem Deen for his translation from Yiddish of the almost illegible recollections of Saul Furleiter. Agnes Grunwald-Spier, a Holocaust historian and a survivor herself, has been an invaluable guide and friend. My history schoolmaster, the late Tony Corten, whom I miss very much, was also an inspiration. Thank you also to Gina Carter, David Burns and David Cummings who helped me to grapple with this endeavour, particularly in the early stages.

Lady Potts and her sons Jacob and George kindly gave us exclusive access to the court transcripts annotated by her late husband, the trial judge, Sir Humphrey Potts. Other leading figures in the trial, including Sir Johnny Nutting QC, Bt, Bill Clegg QC, and defence solicitors Martin Lee and Steve Law, all shared their recollections with us. Thank you also to Sir Adrian Fulford QC and HHJ Mark Lucraft QC, for their very kind assistance and encouragement, and to Chris Watson, Charles Rifkind, Stephen Auld QC, Johnny Levy, Neil Calver QC, Lord David Wolfson and Baroness Scotland, whose enthusiasm has been unstinting. There are many more in the legal community who have provided assistance and support; they know who they are.

We are also grateful for access to the testimonies of Ben-Zion Blustein, Benni Kalina, Saul Furleiter, Miriam Soroka, Michael Omelinski and other survivors of the Holocaust preserved in the Yad Vashem archive in Israel and the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, and the help of the staff at both institutions is much appreciated.

Among many others, we were also privileged to conduct exclusive interviews with Ben-Zion Blusteins son, Shalom and his wife Hanna, and grandson, Ben; his friend and biographer, Margalit Shlain, author of One of the Sheep; Benni Kalinas son Meir; Jack Pomeranc and his son Larry; Sara Omelinsky; and the families of the late Meir Bronstein, Boris Greenstein and Abraham Edelstein, all partisans who fought alongside Ben-Zion in the forests of Belarus.

Professor Chris Browning, who gave expert testimony about Nazi plans and hierarchies at the trial, gave us his insights and reflections, and our thanks to David Hirsh whose chapter about the Sawoniuk trial and support were early motivators. Thanks also to Charlie Moore, a detective with the War Crimes Unit and his wife Jane McCallum Moore who served in the same unit. Charlie shared his insider knowledge of the investigation, and were also grateful for the input of their colleagues Jill Murray and Maggie Newberry, and other former and current Met policemen, including Eddie Bathgate, Richard Blewett, Mike Charlton, Norman Inniss and Matt Shalders. Dr Martin Dean, the WCUs Senior Historian, gave us invaluable insights into the files that he and his fellow historian Alasdair MacLeod had uncovered in archives across the world.

The comments and research papers of Ian Hepburn, for many years the senior crime reporter on the Sun newspaper, have also been invaluable, and were grateful for the help of photographer Ray Collins, and many other reporters, photographers and broadcasters who covered the trial and the historic jury visit to Domachevo. Mike Hookway and some of Sawoniuks other former co-workers and neighbours also shared their memories and opinions of him.

The friendly co-operation of all these people and many others is very much appreciated. Any errors are ours alone.

Further details on the story of The Ticket Collector from Belarus can be found at www.theticketcollector.com

AUTHORS NOTE

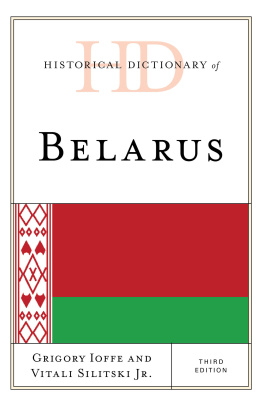

In the course of its modern history, the country that is now Belarus has been known by several other names: White Russia, Byelorussia, Belorussia and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, and was also part of Poland between the wars. To avoid confusion, its modern name has been used throughout.

CHAPTER 1

The story of Great Britains first and only successful war crimes trial is also the tale of the intertwined lives of two men. Childhood friends in Domachevo, they were on opposite sides after the German invasion, with one fighting against the Nazi atrocities that the other was helping to inflict. For over half a century after the war, they lived thousands of miles apart, each unaware that the other had even survived, but fate was to bring them together again, in Court 12 of the Old Bailey in London, in February 1999, where one would face possible retribution, while the other sought some vindication at last for the suffering and loss he had endured.

Ben-Zion Blustein was born in Domachevo, then part of Poland, in 1924. His father died from TB when Ben-Zion was just ten months old, and with his older sister and, later, a sister and little brother seven and eight years younger than him, he was raised by his mother, Shaindel, who ran a grocers shop, and his stepfather, Noah, a furrier. One of his first memories was of his mother wrapping him in a thick wool blanket, putting him on a sledge and pulling him through the snow to the schoolhouse so that the rabbi could begin teaching him Hebrew. She asked him first to teach Ben-Zion to say Kaddish the prayer of remembrance for the dead so that he could recite it over his fathers grave on the fourth anniversary of his death.

Belarus had been part of the Russian Empire until the October Revolution in 1917, and under the old Tsarist laws, Russian Jews had been forbidden to live in cities or agricultural communities, or own land. That forced them to move to villages and small towns like Domachevo where, since they were not allowed to farm, many became merchants, artisans and shopkeepers. They remained there after the Tsars were overthrown and Domachevo became part of the independent Poland, which existed briefly between the First and Second World Wars, and many grew to be relatively prosperous.

There was no ghetto then, no walls or barbed wire separating the communities, but the Jews, who formed the majority of the towns population, lived separately from the Gentiles, in wooden houses with steeply pitched roofs to shed the winter snow, wide verandas at the front and neat gardens at the rear. On Friday and Saturday evenings, every family dressed in their best clothes and, in a Jewish equivalent of the Spanish paseo, promenaded along the main street to see and be seen, exchanging greetings with friends and neighbours, while their teenage sons and daughters swapped furtive glances.

There were two synagogues: the Great, in the marketplace where the wealthy businessmen and merchants prayed, and the Small, in a side street for workers and tradesmen. The two rabbis matched their congregations. Reb Yankel, who presided over the smaller synagogue, had the powerful build of his tradesman father. The other, Leizer Wolf, was a tall, thin, ascetic man who earned his living as a rabbinical judge and studied day and night until he was claimed by TB. His wife, a much smaller, stooped woman, took care of their more fundamental needs, having secured the monopoly of selling yeast for the