Contents

Guide

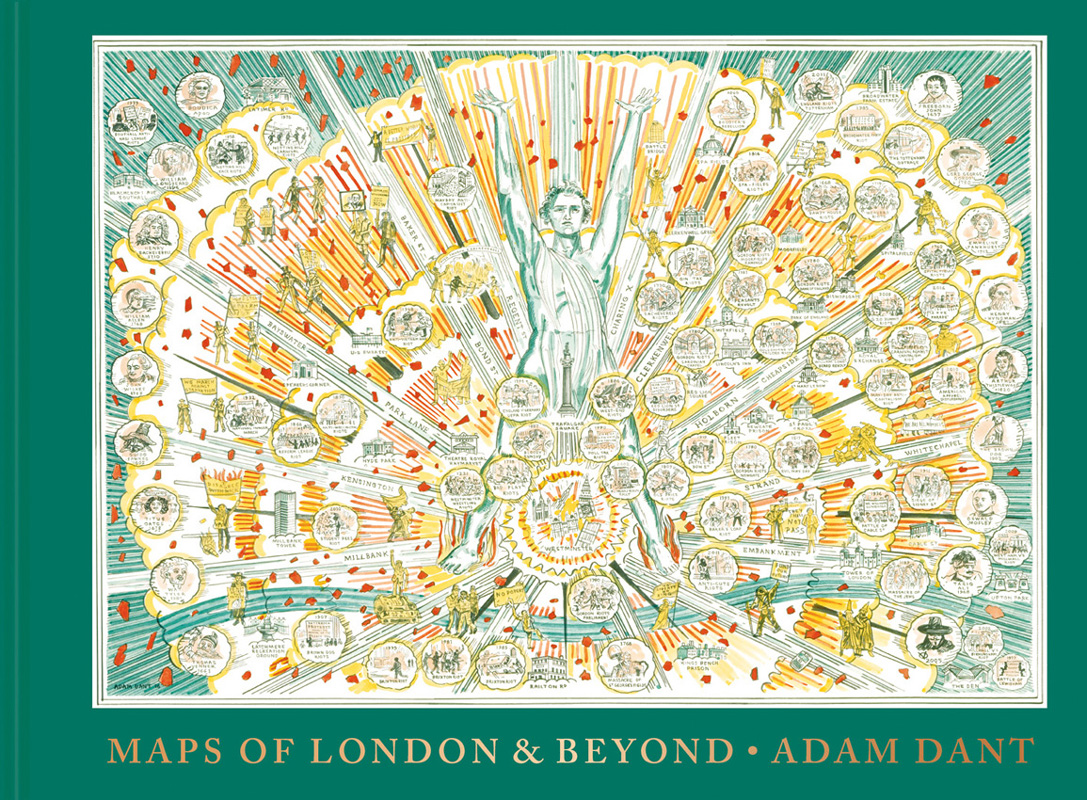

MAPS OF LONDON & BEYOND

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T he Gentle Author visited Adam Dant in his studio in Club Row off Redchurch Street in East London to learn about the origin of his fascination with maps and the pursuit of creative cartography.

The Gentle Author What brought you to the East End of London?

Adam Dant I came here in 1993, directly from Rome, where I spent a year as the Rome Scholar in Printmaking at the British School. I had often visited Brick Lane and Petticoat Lane markets in the past and, growing up in Cambridge, always entered London via Liverpool Street Station. The badly lit, derelict streets surrounding Spitalfields Market, where meths drinkers gathered around bonfires of orange boxes, seemed very dark and dodgy quite the antithesis of Cambridge with its culture of Reason, savoir faire and sandstone Gothic pinnacles. On the evening I returned from Rome, the artists Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas were hosting the closing party for their shop on the Bethnal Green Road, and I bought bottles of brown ale from The Dolphin pub on what seemed to be a very gloomy Redchurch Street, unaware that I would be moving to the neighbourhood within a few weeks.

The Gentle Author Tell me about your studio.

Adam Dant Before I moved in, this building was a minicab office, but it was forced to close because the massive aerial on the roof was interfering with the neighbours television signals. I used to take cabs from here, and I have a vague memory of walking past one evening and seeing it being attacked by a mob of angry, scaffolding-pole-wielding rival minicab drivers. Inside it was a mess: a filthy grey carpet with haphazardly trimmed edges and a couple of Space Invaders games in the corner. I lived here in my studio on Club Row for several years while I was a bachelor. When I moved in, I found I had inherited half a dozen phone lines and a stack of business cards with the words Tower Cars, Fully Insuranced. These fully insuranced owners had sawn all the bannisters off the staircase, which had a length of carpet nailed to it in a random fashion. Upstairs, an ancient water heater held together with dried-out masking tape was dripping in the corner, and chicken wire covered the windows.

The Gentle Author Was the whole street like that in the nineties?

Adam Dant Almost everything in the neighbourhood had become a crumbling wreck while under the charge of dubious landlords who were too parsimonious to spend any money on buildings that seemed of no more value to them than burdensome elderly relatives, despite their hidden charms and bountiful legacies.

In one attic, an entire wall wobbled dangerously when I leant against it. Dont worry, theres a few more years left in that, the landlord told me reassuringly, meaning, If you think Ill be spending any money on this place, dream on. Once I stood with a neighbour and his landlord in an ex-sweatshop, watching flames from a pre-war ceiling-mounted gas heater singe a mildewed flap of wallpaper. Yes, I think the burner seems to be working fine, he reassured us, before stepping over a missing floorboard and walking downstairs to his waiting Bentley.

The building adjoining my minicab office was left derelict and empty for eight or nine years following my arrival. Every few weeks, the owner would appear in a van and throw bundles of leather trimmings through the doorway. Rats lived among the crumbling bin bags and mouldering strips of leather inside. During dinner at my neighbours flat, one of the rats pushed a loose brick from the wall and stuck his furry face through the gap, which rather spoiled the cheese course. Yet despite regular enquiries, none of these people either wanted to sell or restore their collapsing assets and, even today, some of these buildings have received no attention since the Blitz.

At the time I was working at Agnews, the Old-Master picture gallery on Old Bond Street. Some Irish labourers came into the gallery one afternoon and asked if anyone wanted to buy some oak floorboards. They had been using them as ramps for their wheelbarrows while gutting the old Barclays Bank that was to become a handbag shop. I persuaded them to deliver these concrete-spattered planks to my studio the next day for 100 in cash, and I planed and sanded the hefty, wide boards and fitted them upstairs. Downstairs served as The Gallerette for a year. I laid a smart parquet floor to improve the acoustics for an audio exhibition, which sounded muffled without it, and I painted the ceiling in the style of Romes Palazzo Altieri one rainy Bank Holiday.

The Gentle Author Did you find yourself part of a community?

Adam Dant Yes, the community I had entered and which coalesced around me was quite tight, due in part I think to the geography of the neighbourhood, which felt like a walled enclave. It was called The Boundary. The Bengali people who lived on the Boundary Estate worshipped at two mosques on Redchurch Street, and ran the butchers shops, grocers and garment factories, sometimes socializing at St Hildas, our local community centre, where I went to play badminton and run off pamphlets on the ancient Gestetner printing machine.

Here on Redchurch Street, my neighbours worked mostly in creative fields. There were furniture designers, a stained-glass artist, a saxophonist, a gang of Italian lesbian anarchists who drove round in a Fiat Cinquecento painted in pink leopardskin, a playwright, a documentary filmmaker, a rubber garment maker and many more. They lived in the curious collection of abandoned warehouses, shops and offices, and were to be found every night in the Owl and Pussycat, an ex-dog-fighting pub, where the areas history was a frequent subject of discussion. Everyone had read Arthur Morrisons A Child of the Jago and knew the exact location of Shakespeares original Theatre. They spoke about the arcane origins of the street names, claimed that a ley line ran directly through the nicest house, and on towards the bandstand at Arnold Circus. I painted a map that was an aerial view of the area for my friend James Goff who had pioneered this neglected neighbourhood even before the artists arrived in Shoreditch.

The Gentle Author How did your map-making evolve?

Adam Dant The second map I made of my neighbourhood was an attempt to encapsulate the history and the lore of the place as a world unto itself. The area had quite distinct edges, so I depicted Shoreditch literally as a distinct world, wrapping the streets around an imagined globe a reference to Shakespeare, with his theatre and characters populating the streets of my map.

After this, I wanted to create a map of the area in the present day. The idea of creating a map of Shoreditch as it appeared in the dreams of residents came from hearing friends in the Owl and Pussycat describe how, in their nocturnal reveries, they had all shared visions of Shakespeares theatre at New Inn Yard. Pursuing Carl Jungs concept of collective dreaming, I visited the Association of Jungian Analysts in Hampstead for a symposium on this notion. It was hilarious. A young German woman with a severe haircut and a clipboard took notes as the assembled ragbag of North London Jungians, unaware of just how much they were revealing, described incidents from their dreams.