Sharon Doyle Driedger - An Irish Heart

Here you can read online Sharon Doyle Driedger - An Irish Heart full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:An Irish Heart

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Irish Heart: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Irish Heart" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

An Irish Heart — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "An Irish Heart" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

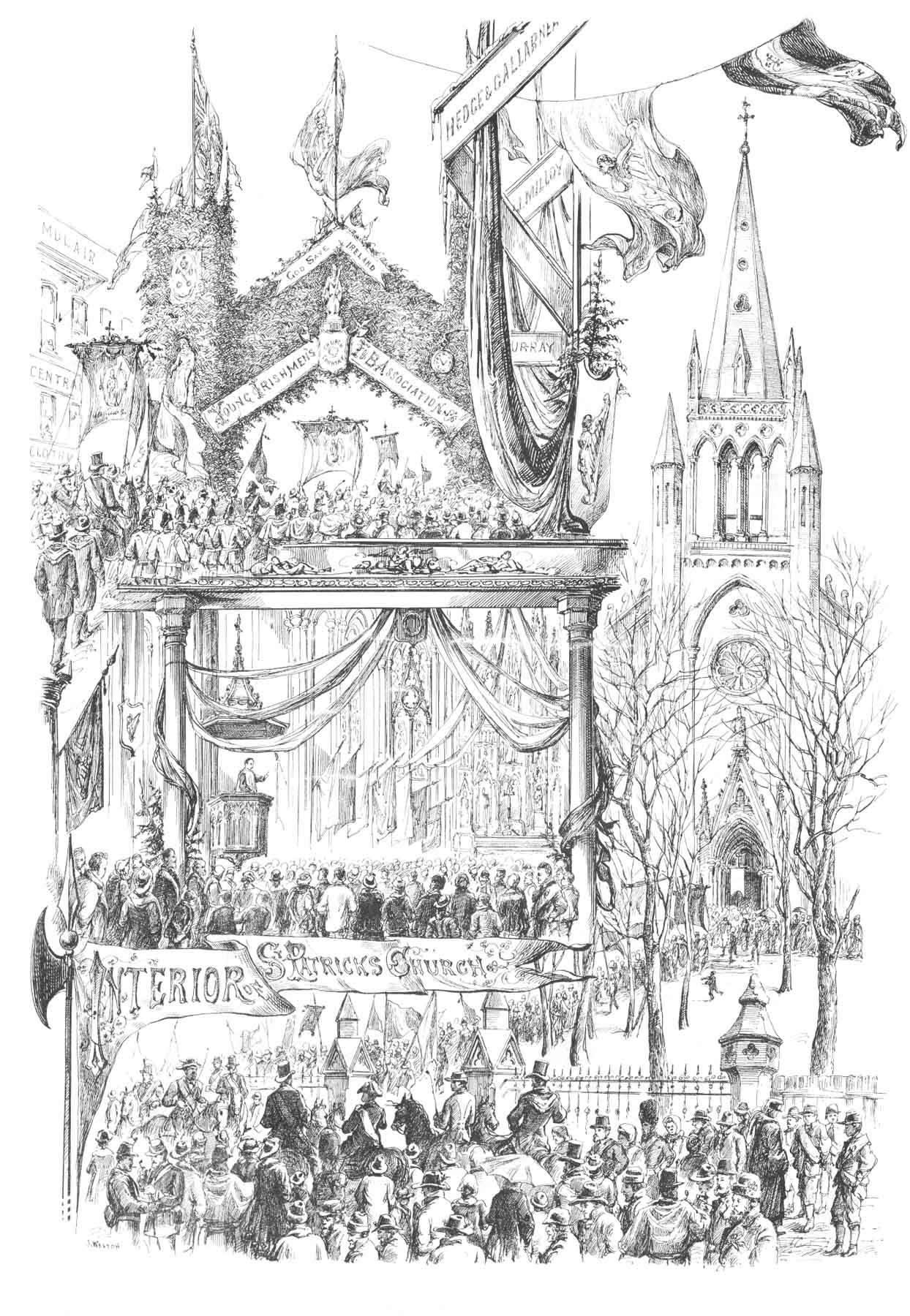

Canadian Illustrated News, March 29, 1879, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library (Toronto Reference Library)

For my family

and

in memory of my father and those who have gone before us

They are flying, flying, like northern birds, over the sea for fear;

They cannot abide in their own green land, they seek a resting here.

Thomas DArcy McGee

Sail on, sail on, thou fearless bark,

Wherever blows the welcome wind;

It cannot lead to scenes more dark,

More sad, than those we leave behind.

Thomas Moore

T HE I RISH CALL IT THE H ARBOUR OF T EARS . From time beyond memory, countless thousands have sailed away from their beloved Ireland from the Cove of Cork, a rare natural harbour tucked into the wild, jagged cliffs of the southwest coast. And as if the land itself were reluctant to let them go, two arms of the River Lee reach inward from the cove, embracing the island city of Cork and caressing the long quays where so many have cried through anguished farewells.

Never did Corks harbour see more weeping and wailing than in Black 47. In that single, sad year, more than ten thousand men, women and children left famine-struck Ireland from that port alone, in an unprecedented exodus of more than a quarter of a million Irish to North America. Nearly half embarked for Canada, carried away on a haphazard fleet of decrepit cargo vessels. Thousands would perish on the grim voyage, their typhus-ridden bodies dumped into the sea. Thousands more would die within days and weeks of landing in the New World.

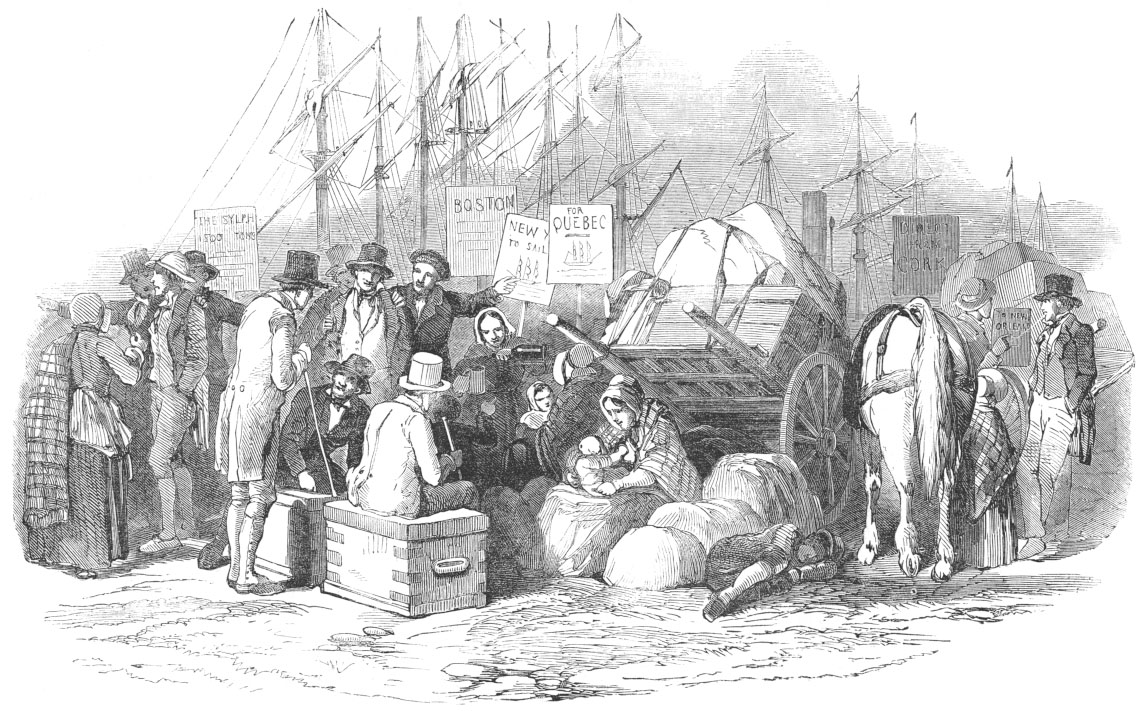

Emigrants bound for Quebec, Boston and other ports wait on a quay at Cork Harbour.

Illustrated London News, May 10, 1851, courtesy of the TPL (TRL)

On Thursday, May 20, 1847, in a gentle Irish rain, Michael Daley and Mary Walsh of Kilbany Parish, Limerick, with their twelve-year-old son, Michael, boarded the barque Avon, bound for Quebec. Thomas Reilley and Mary Barry, of Cork Parish in County Roscommon, went too, with their daughters, Mary, 5, Bridget, 7, and Helena, 12. So did Margaret and John Brien of Mondaniel Parish, County Cork, with their children Ellen, 15, Patrick, 14, and William, 12. By the time Captain Michael Johnston signalled the mate to pull anchor, 552 passengers, all but two of them in steerage, were crammed into the dangerously overcrowded vessel.

The Avon, built in Boston in 1831, would prove to be one of the deadliest of the coffin ships. But as the boat slipped down the River Lee, hope flickered in the exiles sunken eyes. The Avon would take them awayfar from the stink of potatoes rotting in black fields; from the feel of freshly-dug tubers collapsing into slimy mush in their hands; and from the sight of emaciated bodies lying dead by the road, half eaten by rats.

Gaunt and threadbare, the passengers pressed together on the open deck, trying to keep their footing in the swaying vessel, taking in the noise and bustle of the busy port, the shouts and banter of the busy crew. The barques imposing canvas spread to the wind and the Avon heaved forward, past the tightly packed buildings along the quays, past the marshes, out into the cove. On shore, people and cattle in coastal villages went silent, then faded into the misty distance. Past Mizen Head, out into the Atlantic. One last look at Ireland: a thin flat line on the horizon. Then down into the hold, clutching boxes and chests containing a few humble possessions, holy water and a clump of turf or shamrock tucked in for God and good luck.

The misery trailing in their wake had yet to surface.

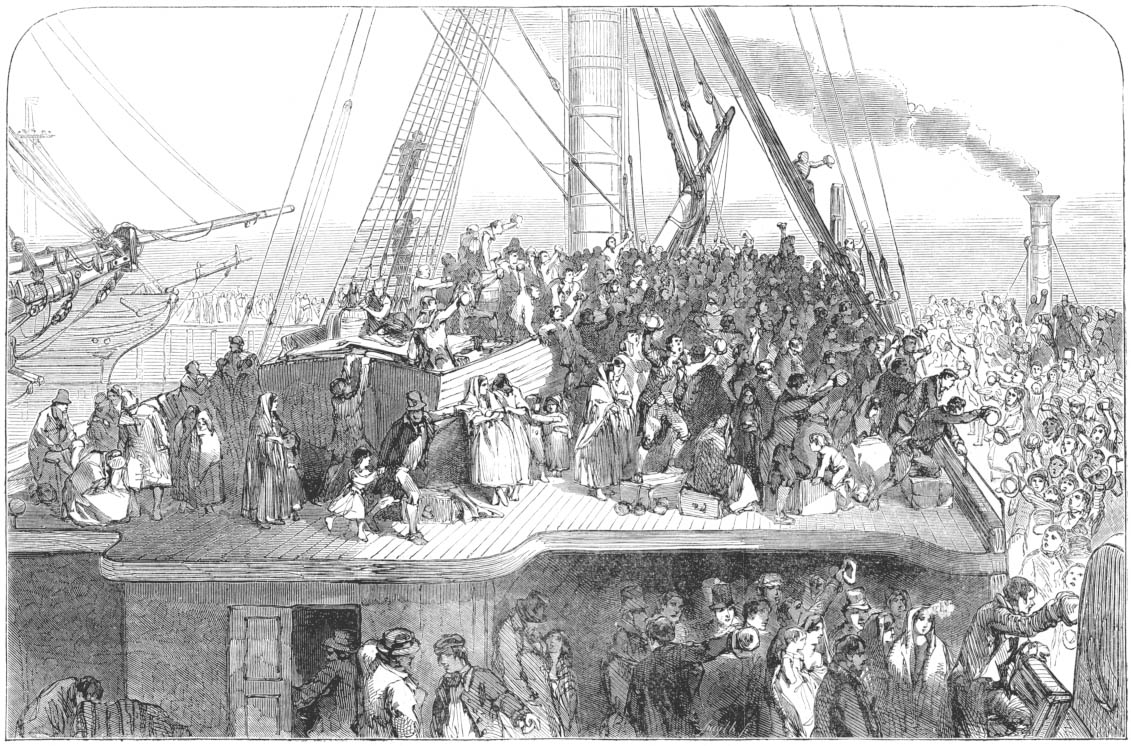

Passengers press onto the upper deck as an emigrant ship leaves Liverpool, port of departure for thousands of Irish.

Illustrated London News, July 6, 1850, courtesy of the TPL (TRL)

A DVENTURE AND AMBITION HAD ALREADY PROPELLED hundreds of thousands of Irishmen across the sea to Canada. The first Hibernian migrs arrived long before the Great Famine, landing in the colony of Newfoundland, the Maritimes and settlements along the St. Lawrence, centuries earlier, with the French and the British, rivals competing for control of North Americas lucrative fur trade and fisheries.

The Irish started spending summers at Newfoundland fishing stations in the early 1600s. Each spring, British fishing boats en route to the Grand Banks would stop at Waterford, Cork and other ports in the south of Ireland, to take on provisions and to hire young Irishmen to work for the season in Talamh an EiscGaelic for land of the fishthe Irish name for Newfoundland.

The wanderlust that had led the Irish to Newfoundland prompted many to move on again; and they gradually fanned out into Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Anticosti and the Magdalen Islands. A few Irish sailed directly to Halifax in 1749, with some 2500 settlers sponsored by British authorities who were eager to establish a fortified town on the Nova Scotia coast. And they were soon joined by indentured workers from the Newfoundland fishery, trying to escape their harsh contracts. Within a decade, their numbers had increased to nearly three thousand, enough to lead one British resident to complain that the common dialect spoke at Halifax is wild Irish.

Irishmen had begun to trickle into Quebec in the seventeenth century. OSullivan, Casey, OBrennan and other Irish names appear in land documents and census records as early as 1625. Nearly one hundred of the twenty-five hundred families registered in the parishes of New France in the late 1600s originated in Ireland. By then, members of the legendary Irish brigade known as the Wild Geese had made their way to the French colony.

The Irish Catholics soldiers had found a ready ally in France, after their exile from Ireland in 1691. They had lost the infamous Battle of the Boyne on July 1, 1690, a turning point in an epic struggle for the English crown. The war, fought on Irish soil, had pitted supporters of the deposed Catholic King James against those of King Billy, the Protestant William of Orange. The Irish army, largely Catholics, had resisted their oppressors for more than a year after their bitter defeat at the Boyne. But the soldiers were forced out of Ireland en masse after the Battle of Limerick in 1691a Protestant victory that would usher in centuries of oppression of Irelands Catholics under increasingly severe Penal Laws.

Irish emigration to Canada began in earnest after the French lost their hold on North America. Louisbourg fell to the British in 1758, followed by Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760. Almost as soon as the hostilities ended, British entrepreneurs looked to the colonies for business opportunities. And the Irish came streaming in behind them, encouraged by the British who were eager to populate their newly acquired territories with loyal subjects.

So many sons of Erin had settled in the Maritimes, that when the British decided to carve a new colony out of Nova Scotia in 1784, William Knox, the provinces Irish-born undersecretary of state, proposed naming it New Ireland after his native land. King George III demurred, choosing instead to call it New Brunswick in honour of a German prince.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «An Irish Heart»

Look at similar books to An Irish Heart. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book An Irish Heart and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.