Thank you for downloading this Sourcebooks eBook !

You are just one click away from

Being the first to hear about author happenings

VIP deals and steals

Exclusive giveaways

Free bonus content

Early access to interactive activities

Sneak peeks at our newest titles

Happy reading !

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Books . Change . Lives .

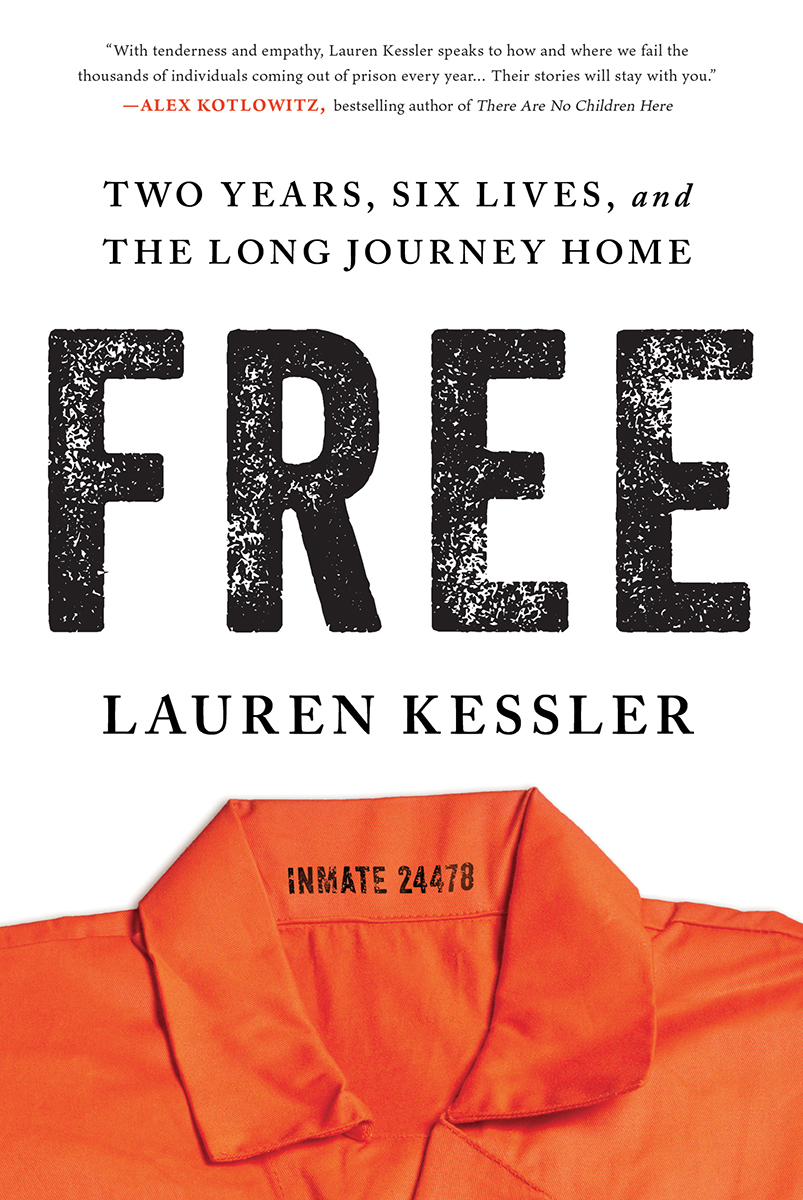

Copyright 2022 by Lauren Kessler

Cover and internal design 2022 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by Heather VenHuizen/Sourcebooks

Cover images Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

Published by Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kessler, Lauren, author.

Title: Free : two years, six lives, and the long journey home / Lauren Kessler.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks, [2022] | Includes

bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021052691 (print) | LCCN 2021052692 (ebook) |

Subjects: LCSH: Ex-convicts--Social conditions. | Ex-convicts--Services

for. | Prisoners--Deinstitutionalization.

Classification: LCC HV9281 .K47 2022 (print) | LCC HV9281 (ebook) | DDC

364.8--dc23/eng/20211105

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052691

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052692

Contents

For Cheryl, Karen, and Karuna

H ope is like the sun,

w hich, as we journey toward it,

c asts the shadow of our burden behind us

SAMUEL SMILES

Authors Note

This is a work of nonfiction.

Because the line between fact and fiction has recently become blurred in ways many of us could never have imagined, I want to be clear: All the people in this book are real. None are inventions or fabrications. There are no composite characters. I have not knowingly changed any facts or details about them or their lives, with the following exception: I did change the names of the characters I call Vicki (as well as her partner and children) and Dave. Unlike the others whose reentries are chronicled here, these two lead private lives, and I chose to protect that privacy.

All the events you will read about are real. All the conversations are real. I have chronicled these as faithfully as I know how. Many I directly heard and witnessed or participated in. Some are the products of multiple in-depth interviews. A few were gleaned from audio, video, or text records kept by others.

Any liberties I have taken are liberties not of fact but of interpretation. I saw these people, these events, through my own eyes and filtered them, as all nonfiction writers do, through my own sensibilities. I mean to respect these people who let me into their lives. I mean to shed a light on their journey. I mean to tell truths both factual and emotional.

Prologue

When she was eighteen, Belinda was convicted of stabbing her pimp. She hadnt meant to kill him, just hurt him. Shed been on the streets since she was fourteen, when her mother stopped the car and told her to get out, and she had learned to take care of herself. Or at least stay alive. She spent the next twenty-two years behind bars. The day she was released from the Coffee Creek Correctional Facility, it was raining. She was wearing sweatpants a size too large and a cheap nylon jacket, clothes brought in by a friend the day before. She was lit up, like a girl rushing out to meet her prom date. There was no prom date. There was a clutch of late-middle-aged women from a faith-based group that had connected with her in prison. There was a dog. It was one of the dogs she had helped train as part of a prison-run canine companions program. She briefly hugged the women then got down on one knee and nuzzled the dog for a long moment. The dog remembered her.

The ladies knew exactly where Belinda wanted to go. In two cars, they caravanned to the nearest Starbucks, less than two minutes away. Shed heard about this Starbucks from someone inside, a woman whod come to prison more than a decade after Belinda. Belinda hesitated at the door. Two of the ladies walked in. A third stood next to her, waiting, silent. Then she gently laid a palm on Belindas back and ushered her in. They found a table. They ordered for her. She wanted a caramel Frappuccino. Someone had told her about caramel Frappuccinos. When she took that first sip, she closed her eyes.

***

A month later, Belinda and I sit in a booth at a chain steak house. She had allowed me to witness her release that day because we had connected while she was still inside. I had interviewed her about her experiences with the prisons hospice unit, where inmate volunteers sat with the dying as their lives ended behind bars. It was part of my research on incarcerated life that became my first book about life inside prison, A Grip of Time . I liked Belinda. She was tough. She had to be. But the hospice work had, I thought, touched a place inside her that maybe had not been touched before. I wanted her to do well on the outside. I thought I owed her at least a dinner for the time she spent answering my questions, for her honesty. And so I had proposed this get-together.

Now, sitting across from her, I take note that she has ordered the most expensive item on the menu plus three extra sides. The food on the plates in front of her could feed a family of four. Belinda hardly touches it. She has not looked up from her phone since we sat down. A month ago she had never held a smartphone in her hand. Now she is nonstop texting with her thumbs. She had gotten the phone three weeks before. She had acquired a boyfriend a week later.

She was in the throes of what sociologists call asynchronicity. While Belinda was in prison, her age cohort moved on. Inside, time was frozen. Outside, other young women acquired (and dumped) boyfriends or girlfriends, went to concerts, got (and lost) jobs, maybe went to college. On the outside, other young women moved to new apartments, new towns, new countries, had adventures, changed their look, had career aspirations that worked out or didnt. On the outside, other young women grew into their thirties, found their place, lost it, reinvented themselves, settled in. They had children. Inside, Belinda had experienced a lot, but none of this. At forty, she was still in many ways a teenager. She was a teenager with a new phone texting a new boyfriend.

I watch her. Her hair is dyed matte black. Her eyes are thickly rimmed with black eyeliner. I can see a light etching of crows feet in the corners of her eyes. She has that hard look women have when theyve spent a lot of time in prison. She looks her age, maybe older. Prison does that to you. But she acts like a high schooler. I wonder what this disconnect might mean for her reentry. That night I offer to mentor her, be a sounding board, listen to her stories, take her out to lunch or dinner every few weeks. She agrees.