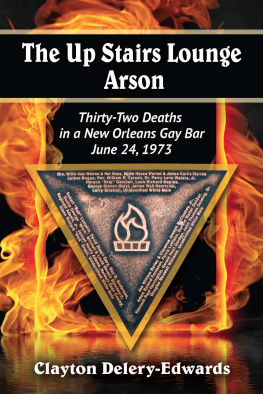

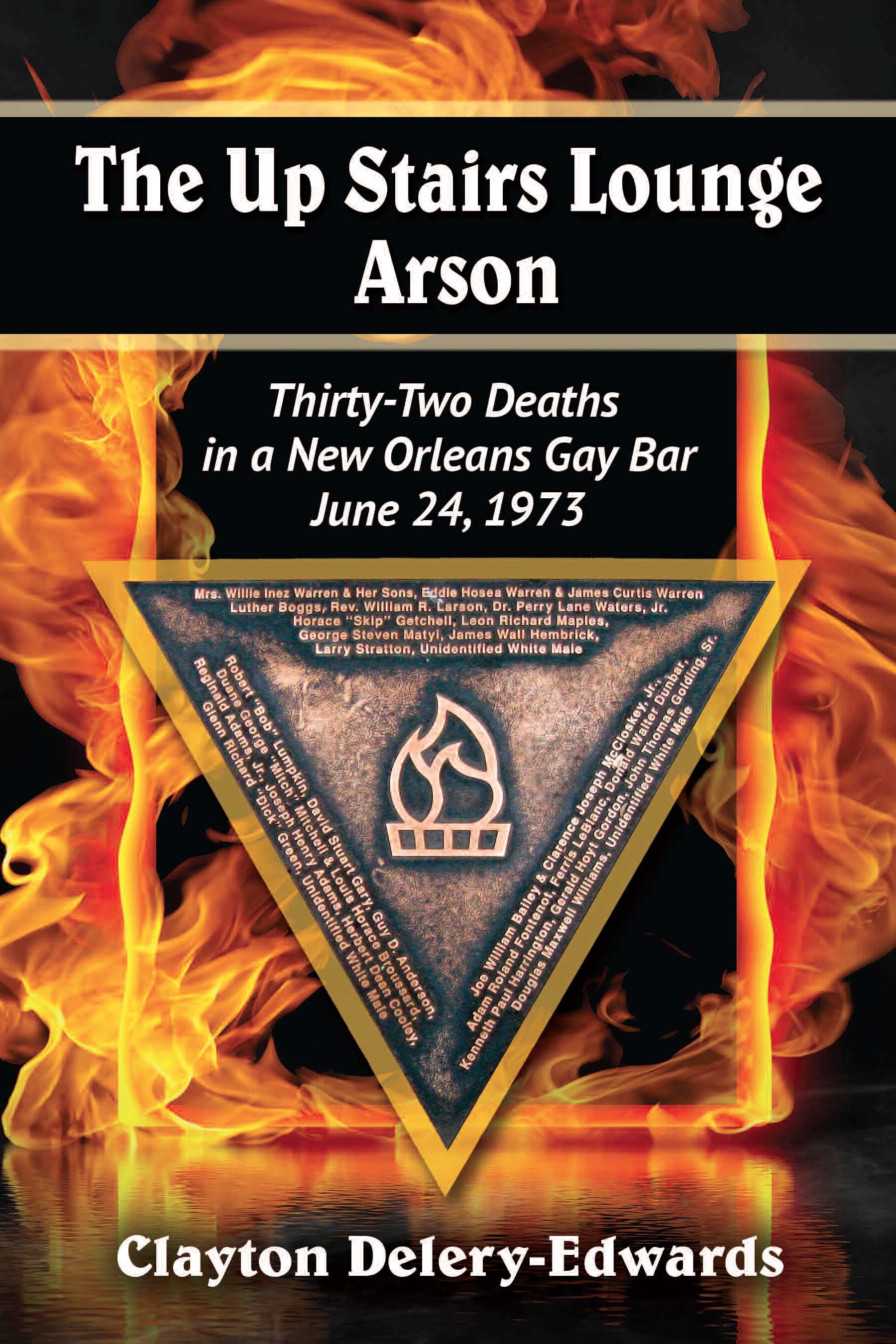

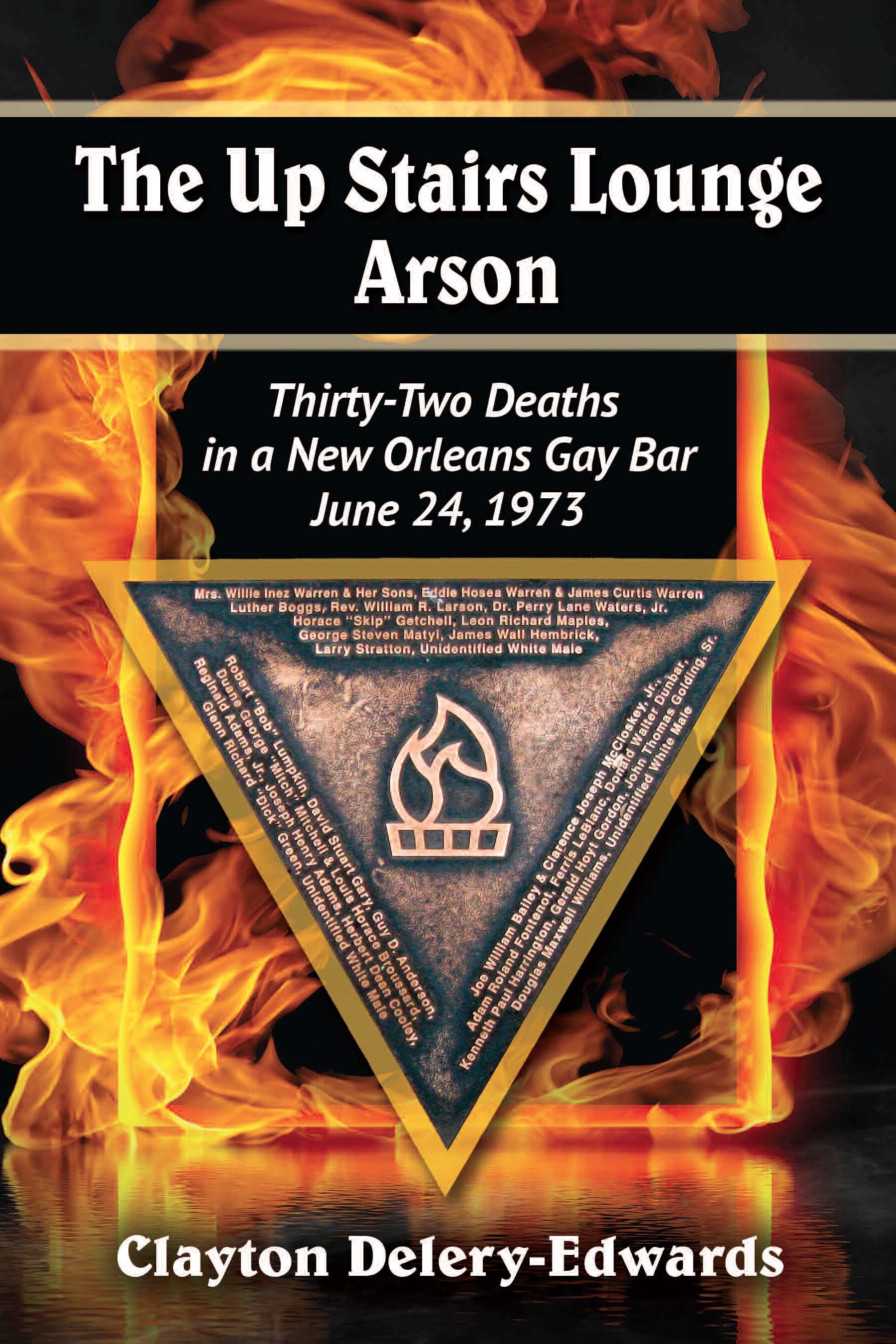

The Up Stairs Lounge Arson

Thirty-Two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973

CLAYTON DELERY-EDWARDS

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1720-6

2014 Clayton Delery-Edwards. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: plaque now on the sidewalk outside the Up Stairs Lounge, commemorating the fire (Clayton Delery-Edwards), background image iStockphoto/Thinkstock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To all those who died,

especially three unidentified males,

and Ferris LeBlanc,

who was identified, but never claimed

Acknowledgments

Writing can be an isolating enterprise, but it is also a surprisingly collaborative one, and I have many people to thank for their support and assistance.

I am extremely grateful to the people who agreed to interviews or who wrote to me, via mail or email, and shared their experiences. These people include former patrons of the Up Stairs Lounge, survivors of the fire, participants in the subsequent memorial services (particularly those on June 25 and July 1, 1973), as well as others whose experiences, research and expertise have become entwined with the story of the fire. Whether their words appear in the text or not, they have been instrumental in helping me make sense of what happened. My thanks to Regina Adams, Roberts Batson, the Rev. David Billings, the Rev. Dexter Brecht, the Rev. Paul Breton, Stewart Butler, Phillip Byrd, Jack Carrell, the Rev. Anita Dinwiddie, Clancy Dubos, Francis Dufrene, Steven Duplantis, Aaron Edwards, Skylar Fein, Vince Fornias, James Hartman, Carey Hendrix, Charles Kaiser, Henry Kenner, Paul Killgore, Crystal Little, Marcy Marcell, Jim Massaci, Jr., Toni Pizanie, the Rev. Troy Perry, Richard Pool, Lawrence Raybourne, Javier Sandoval, George Tresch, Steven Whittaker, and the Rev. Carol Cotton Winn. If I have left anyone out, I apologize for the oversight.

I owe a great debt to Johnny Townsend, author of the only other book on the Up Stairs Lounge, Let the Faggots Burn. Although Mr. Townsend and I have never met in person, we have emailed each other throughout the past five years, and he was kind enough to grant me permission to draw upon his book. He might logically have regarded me as a rival, but in an early email he wrote, In regard to this fire, all I ever wanted was that the story be told. Let the Faggots Burn is based heavily on interviews with patrons and survivors of the Up Stairs Lounge conducted in the late eighties and early nineties. By the time I began my book in 2009, many of these people had died, and many others, tired of reliving such a traumatic experience, were no longer willing to speak. Johnny Townsend was also good enough to send me a treasure trove of photographs he has collected, which help bring visual life to the story.

Aside from Johnny Townsend, there is a small but very collegial group of writers, composers, artists and filmmakers documenting the Up Stairs Lounge: Royd Anderson, Robert L. Camina, Jim Downs, Skylar Fein, Frank Perez, Wayne Self and Sheri L. Wright. They have all been generous in sharing thoughts, contacts, photographs and illustrations, documents, and support. Of special note is the Rev. Paul Breton, who was good enough to share with me the journal he kept in 1973 as he helped give comfort to the survivors and plan memorials for the dead.

I spent many hours investigating the news coverage and the paper trail from the various investigations into the fire, and doing so meant that I haunted several libraries for days or weeks at a time. My thanks to the Louisiana state fire marshal, H. Butch Browning, for giving me access to the records of the arson investigation, which are held in a special collection in the Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge, and my thanks to the staff at the Louisiana State Archives for helping me go through boxes of un-indexed files so that I could locate the records. Thanks also go to the reference, microforms and archival staffs of the following libraries: the Edith Garland Dupre Library at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette; the Troy H. Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge; the Louisiana Collection of the New Orleans Public Library; the Howard-Tilton Library at Tulane University, New Orleans; Watson Library at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana; the Earl K. Long Library at the University of New Orleans; the Williams Research Center of the Historic New Orleans Collection; and the One National Gay and Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles, California.

Once I acquired hundreds of pages of notes, transcripts, photocopies, articles and emails, I had to put them in some kind of order. There were thousands of details to consider, each significant in its own way, leaving me with the difficult job of deciding which to include and which to omit so that I could present a fair and comprehensive narrative without confusing or overwhelming the reader. For their assistance in critiquing and editing my drafts, I thank the members of the Cane River Writers: Nahla and Bill Beier, Carolyn Breedlove, Joanna Cassidy, Carol Connor, Cedelas Hall, Julie Kane, Stephanie Masson, Margaret Pennington, Frank Schicketanz, and Mary Kay Waskom.

Finally, for listening to me talk about this project for several years before saying, Just write the book already! I thank my beloved husband, Aaron Delery-Edwards, who encouraged me at every step and who was poorly rewarded by having to endure many weeks when I was more fully alive in 1973 than in the present. Sweetie, youre the best.

Preface

The 1973 fire at the Up Stairs Lounge is the deadliest fire in the history of New Orleans. This is not an easy distinction to achieve. The city has had many notable fires in its nearly 300-year existence, including two in the eighteenth century that both came close to destroying the struggling young settlement. The Up Stairs fire was brief; firefighters extinguished the blaze only 16 minutes after getting the call. The damage was limited to a single building, which survived the fire and still exists. Even so, that quick blaze killed 29 people within minutes, and three more later died of their injuries. Arson was immediately suspected and, though a likely suspect was soon identified, there was never an arrest or a trial.

The fire received extensive newspaper and television coverage, both locally and nationally, but the story died down sooner than one would have expected. Sooner, frankly, than some people thought was appropriate, or even decent. Leaders from the government, church, and community were surprisingly silent regarding the event. To most people today, the reasons seem simple: the Up Stairs Lounge was a gay bar, and nearly all who died were gay men. In the early 1970s, journalists didnt really know how to treat issues regarding LGBT people, and public officials were often either hostile to this population, or embarrassed to support it too openly.

Because there was never an arrest or a trial, many questions have remained officially unanswered, creating a perfect environment for rumor, speculation, and conjecture. The fire is often reported as a hate crime. There are stories of a gasoline-soaked shirt being found at the site, and of Molotov cocktails being thrown in the windows as victims died inside. Because the suspect was never arrested, there are rumors of conspiracies, some involving a hostile police department that just couldnt be bothered solving a mass-murder of gay men, and some involving the Mafia wanting to protect the culprit from prosecution. Some people argue that the fire became the New Orleans equivalent of the Stonewall riots in New York, which took place four years earlier, and say that the Up Stairs fire fostered the birth of gay activism in the city. Some people say that it had no effect on the social or political culture of New Orleans at all.

Next page