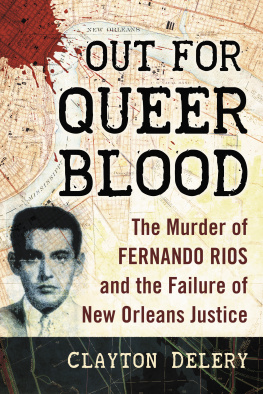

Out for Queer Blood

The Murder of Fernando Rios and the Failure of New Orleans Justice

CLAYTON DELERY

Foreword by ROBERT L. CAMINA

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2987-2

2017 Clayton Delery. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: (bottom inset) The only known photograph of Fernando Rios, published on October 2, 1958, in The Times-Picayune (The Times-Picayune Archive/Advance Media); (background) 1951 map of New Orleans (U.S. Geological Survey)

Exposit is an imprint of McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.expositbooks.com

To the memory of Fernando Rios

Acknowledgments

Nobody writes a history book without a lot of help.

For various personal, telephone, and email interviews, I would like to thank the following people: Roberts Batson, Milton Buras, Albert Carey, Angela Durden, Chase Edwards, Sean Farrell, Donald Carl Hodge, Jr., William McDermott, Bridgett Preau, Walter Preau, Allyson Prejean, and Steven Whittaker. Mr. Farrell told me about the man he knew his father to be. Other people who gave me interviews helped fill in my gaps about what life was like for gay men in New Orleans in the 1950s. Still others gave me the benefit of their expertise on psychological, medical, or legal issues. I am in debt to each and every one.

To Ms. Terri Guerin, who works in the office of the New Orleans Clerk of Criminal Court, I owe thanks for giving me permission to view the relevant docket files, and to Eddie Gonzalez, an employee of the Louisiana State Supreme Court, for doing the same.

I owe thanks to archivists and librarians at the New Orleans Public Library, the Howard Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University, the Earl K. Long Library at the University of New Orleans, and the Williams Research Center at the Historic New Orleans Collection. A special shout-out to Bill Stafford at the Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge, who has now helped me with several projects. Im sure he must groan when he hears from me, because he and his staff invariably wind up digging out dusty boxes full of uncatalogued or barely catalogued items, but they always do so with good cheer.

To the Cane River Writers, who have taught me so much about what makes good writing, I owe thanks for years of help: Bill Beier, Nahla Beier, Carolyn Breedlove, Joanna Cassidy, Carol Connor, Cedelas Hall, Katie Hanson, Julie Kane, and Mary Kay Waskom. Similarly, I owe thanks to Jordan Chauncy for being a reader from the next generation. Jordan helped me understand exactly how much background knowledge about the 1950s I needed to provide for people now in their teens and twenties. Jordan also reads with a very sharp eye for all kinds of errors, and his suggestions have been invaluable.

To Lambda Literary, Id like to express gratitude for choosing me to be a fellow at the 2016 Writers Retreat. The input I received from my teacher, Sarah Schulman, and from my colleagues in the Nonfiction workshop, proved invaluable as I was finalizing this manuscript. Plus, the retreat was a lot of fun!

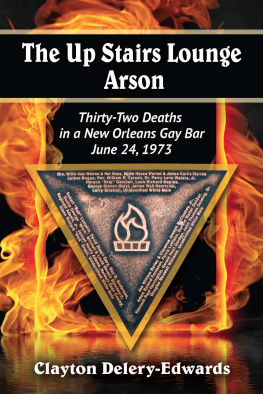

Finally, thanks to Aaron Edwards, who has suffered through the process of me writing two consecutive books about dead gay men from the past. I was not always able to detach from my work at the end of the day, and I was frequently dwelling on autopsies, police investigations, or courtroom procedure when he would have preferred to discuss just about anything else. These books have also meant that we were frequently living in separate decades, even when we were in the same room. Aaronthank you for your patience.

A Note on Language

Our use of language changes constantly. Slang words come and go, words that are considered acceptable in one decade are considered unacceptable in the next, and new words are coined to describe new concepts or things. In writing a book about events that happened nearly 60 years ago, I have encountered many gaps between current and past vocabularies, and have had to find ways to deal with them.

In contextualizing the killing of Fernando Rios, I have given extensive discussion to how various minority populations were seen in the 1950s. Because the crime took place in New Orleans, where black-white relations were fraught with tension in the 1950s, and when prejudice against Latinx people was at a high point, race became a recurring issue in the book.

Many words used to denote racial or ethnic categories (Asian, Hispanic, Negro) are routinely put in the upper case, so I have chosen to do the same when the words White and Black are used in the same way. However, when quoting source material, I have used the case that appears in the source. I apologize if this causes any confusion.

We still refer to Caucasians as White people. Today we often refer to Black people or African Americans, but the polite terms in the 1950s were Negro, Colored, or, occasionally, people of color, a term which has enjoyed a resurgence in recent years. In addition, there were various impolite terms which sometimes occurred in my source documents. When quoting, I have used the term that was used in the source; elsewhere, I have made contextual decisions about which terms to use.

Similarly, while today we generally refer to male homosexuals as gay, the polite terms in the 1950s included homosexual, pervert, deviate, and invert, and the impolite terms included fag, faggot, andmost prominently in this storyqueer. Though queer, like of color, has been reclaimed in recent years, it was distinctly derogatory in the 1950s.

Immigration from Mexico emerged as a theme, in part because Fernando Rios was a Mexican citizen visiting New Orleans at the time of his death. I have made several references to Operation Wetback, which was how one particular immigration initiative was known, and in one or two places I have quoted the term wetback when it was used in a source document. I apologize for any offense this may cause.

The term hate crime did not arise until the 1980s, and the legal concept of the gay panic defense or homosexual panic defense seems to have arisen in the late 1960s. Similarly, the concept of stochastic terrorism has only been in use for a few years. Because I am writing about the years 1958 and 1959, I have avoided using all of these terms until chapters six and seven, when I talk about their histories, then use them retrospectively to show how they applied to the Rios killing.

The rest of the book should speak for itself.

Foreword by Robert L. Camina

I consider myself an accidental activist. On June 28, 2009, police violently raided the Rainbow Lounge, a newly opened gay bar in Fort Worth, Texas, resulting in multiple arrests and serious injuries. In an unfortunate twist of fate, it occurred on the 40th anniversary of the raid of New Yorks Stonewall Inn, an event that is considered the launch of the modern gay rights movement in the United States. The parallels between the two raids were haunting. I had friends at the Rainbow Lounge on the night of the raid. The next morning, as details emerged, I was horrified, angry and sad. Alongside my friends and scores of LGBT citizens and allies in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, we immediately assembled for a rally. We called for a full investigation and demanded that the officers be held accountable for their actions and homophobic rhetoric. Outrage and intense activism led to many changes in Fort Worth, and the city affectionately referred to as Cowtown ultimately became a leader in LGBT equality. I am a filmmaker by trade, but the Rainbow Lounge raid was the genesis of my journey into activism and history preservation. I decided to produce a documentary about the raid and its aftermath so we could use the events as a tool to help educate and inspire. The result was