Table of Contents

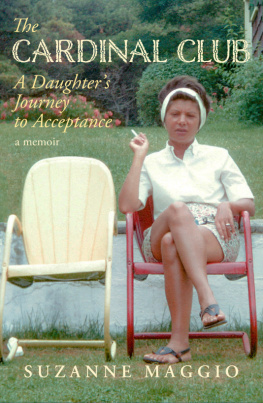

For all the wives and mothers left behind

Authors Note

These pages embark on a gritty and absurd journey. My telling of divorce is probably not for the squeamish or the morally impeccable. If you are any of these things, put this book back on the shelf. Do it right now.

Ive changed plenty of details and events too squalid and banal to inflict upon both you and the innocent.

It should be noted that my son and I are well and happy... he and his father are quite close. So there is hope, even though there is also despair and the destruction of hope. I consider divorce the most ugly word in the English language and it set me free.

l

Denial

We do not see things as they are.

We see things as we are.

Anas Nin

Flight

By the time N left, running out of the house one evening with nothing but the clothes on his back and a voluminous gym bag, I had loved him for seven years. The die was cast.

I see it now as if it is freshly happening, the two of us facing off on a stage set, each in our appointed place for a major scene. It was a cold Friday night, the end of the week, a time primordially loaded for endings and therefore immaculate, befitting. My husband was methodical about everything he chose to do. He also had the trick of making set plans seem spontaneous.

I am wearing a fitted white shirt rolled at the sleeves, black cigarette pants, and red lipstick. Im also wearing shoes with spike heels, something I normally dont do around the house. I want height. I am aware that Ive been waiting for him, have recently started to prepare for his homecoming as I would prepare for a first date.

In our builders grade kitchen, I am alone yet still conscious of posture and makeup, makeup I now wear every day, a dubious bow to vanity. Putting on my Face, my mother, Bunny, calls it. War paint is what I thought as I applied sheer foundation and eye pencil, brushing my eyebrows upward in small, intense strokes. My hands shake and I dont know why. The walls shimmer, too white; my fault: Ive never been good at discerning shades of color. Makeup seems to complicate this problem, engage it. I stay with neutral tones. I check my lipstick in the chrome toaster. I am distorted, but the lines are all there.

Precisely at 6:10, he walks through the rain-spattered oak door and kisses my cheek. I breathe the scent of his neck and something else, some nascent excitement or fear. As he kisses my cheek, his sinewy hands are already on the martini shaker, mixing himself a drink. I take two chilled glasses out of the freezer, placing them next to a bucket of crushed ice. I spear olives (three) onto red plastic toothpicks; drop them into the clear icy liquid just as he is pouring out his first cocktail. He tells me I look beautiful and walks swiftly downstairs to our bedroom to change his shirt, though we have no plans that I am aware of.

I have been greeted and kissed in the smooth normalized way of a television show housewife. I am now waiting for some form of recognition that I exist beyond the second dimension, that we both exist together. The fact that it has come to this is not outside my consciousness, but it seems to be muffled. I love N and he loves me, although not as much as I love him; I accept this. We have A, our toddler son, and I am playing it through.

And yet here he comes, here it comes.

He capers up the carpeted stairs; slung over his arm is a charcoal wool blazer, his best. It is then I feel the fear itself, a small, ghastly tapping at my right shoulder.

I hand him an oversize frosted martini glass, his second in ten, maybe five, minutes. He takes it with one hand, the other busily buttoning his fresh dress shirt, tearing out the paper collar stay, and letting its ragged length fall with uncharacteristic carelessness to the floor.

In my mind this is the formal beginning of the end: his visibly urgent need for fresh attire, the copious vodka, his odd pheromones, the unauthorized appearance of the blazer. Yet I know that this is not the real beginning of the end, this is illusion, a false start. It is only my primitive marking in time. The real genesis is forbidden to me, vis--vis Ns inability to confess even the mildest transgressions. His beginning of all this, both psychologically and physically, has been sliced with great precision from my wifely vista. Theoretically, he wants his way without inflicting pain or suffering, this I know.

Yet he is saying something, my husband, actually several things at once, each more shocking and flamboyantly absurd than the last, like watching dozens of clowns exit a Volkswagen.

Were different people....

I stand with a jar of garlic-stuffed olives in hand, motionless, waiting for exactly how, in his estimation, different we were, and why he is speaking to me as if someone else, a third party, were listening. Outside the kitchen window, redwoods loom silent and apart. A master shot would establish a simple wood-shingle house perched atop Madrone Canyon in the town of Larkspur, population 12,014. A split-level hodgepodge of bright rooms and jutting decks, a vase of calla lilies splayed like a white hand at the kitchen windowsill. Through three large bay windows we see a robust male and a statuesque wife and mother meeting companionably at the end of the day in Marin County, home of an elite group of perpetually concerned wealthy Californians who materialize en masse at the Sausalito Art Festival each Labor Day, purchasing signed lithographs, Zen fountains, and wind chimes. Our house is modest by county standards; it is small but well appointed with a two-car garage. There are no illegal rental units, no recreational vehicles, and no aluminum siding or driveway mechanics. Everything is up to Code, although our refrigerator is leaking. I can see a small pool of ice water at its base. I have to stop myself from cleaning it up as he stands there.

I DESERVE HAPPINESS, N said, raising his voice.

Escalation. Oh, dear. N orates with a large, clear martini glass passing through my airspace, vodka sloshing onto the carpet in a gesture of freedom. Yet I was lulled by his predictabilityonce again, without preamble or rational discussion, he was stating his inalienable human right to have happiness in his life. By now this was a popular theme in our home, Ns Happiness, a kind of precious yet difficult pet. It had become repertoire and had lost some of its original force. Although Id never said so, it all sounded as whimsical as a lost pinwheel. He (we) have everything... gainful employment, a home, health, a sound child. Food, warmth. It ought to be enough; he shouldnt force us all to go delving on some quixotic hunt.

Its his happiness, I thought, slightly hysterical by now. Therefore he should find it on his own. Had he looked everywhere? I almost laughed; a small titter escaped my lips. From this brittle emotion I stepped off, as if from an unseen curb, into a different life.

I hear N say Divorce; and then the word Lawyer coming at me, a javelin.

I put down the olives and place my hands in my hair, tugging at its roots to create a counter sensation. I am not crying yet, but my throat burns. Updike claims if you talk about divorce it will happen. Yet we were not talking about it; I was being informed, and he was leaving at once. Intellectually, I knew this was often how it was done: quickly, like a careful exchange of hearts, a swift transplant. A heart can stop beating for a while, one can still live.