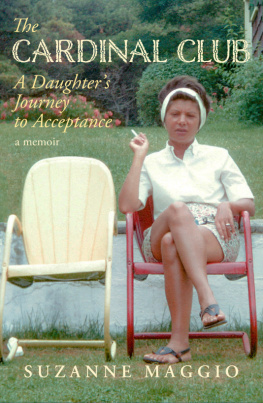

THE CARDINAL CLUB

THE CARDINAL CLUB

A Daughters Journey toAcceptance

A memoir

by

Suzanne Maggio

Adelaide Books

New York/Lisbon

2019

THE CARDINAL CLUB

A memoir

By Suzanne Maggio

Copyright by SuzanneMaggio

Cover design 2019 AdelaideBooks

Published by Adelaide Books, New York /Lisbon

adelaidebooks.org

Editor-in-Chief

Stevan V. Nikolic

All rights reserved. No part of thisbook may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without writtenpermission from the author except in the case of brief quotationsembodied in critical articles and reviews.

For any information, please addressAdelaide Books

at info@adelaidebooks.org

or write to:

Adelaide Books

244 Fifth Ave. Suite D27

New York, NY, 10001

ISBN-13: 978-1-951896-56-0

For my mother

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Although Ive spent more than thirtyyears helping families face the stories they could not face, Icould not face my own.

It was the fall of 1991. Iwas a young social worker, married for five years and pregnant withmy first child. While I tried to appear calm, my stomach was doingflip-flops, the way it so often did when I was about to speak mytruth. I tugged at the blue cotton sundress that stretched acrossmy growing belly and tightened my grip around the scroll of butcherpaper that lay in my lap. Was I ready toshare my story?

Id signed up for an advanced seminarin family therapy and the instructor had assigned us the task ofdrawing our genogram. It is a tool used in therapy, a visual imagethat illustrates the people and connections in a family. It is usedto help families share their history. This was the second time Iddone such an exercise. The first was early on in my social workcareer, when I was in graduate school, newly married and stillstruggling to find my way in the world. Strangely, few things hadchanged since then. Five years later, most of my grandparents werestill alive. My brother and his wife had two children, but not muchelse was different. I drew double lines to indicate the strongrelationship connections between my parents, grandparents andvarious sets of aunts and uncles. My grandmother Maggio had beendiagnosed with cancer a few years earlier, but most of the othermembers were healthy. I scribbled the word Italian above bothfamilies in bold letters.

My colleagues introducedus to their mothers and fathers, brothers, sisters andgrandparents. On the surface, the genogram drawing seemed simpleenough. A series of circles and squares, straight lines and brokenones. But images can be deceiving. It was behind the symbols thatthe richness lay. Stories of first dates, marriage and subsequentdivorce. Alcohol abuse, addiction and a struggle to recover. One ofmy classmates grew up an only child. Another, his family withbarely enough to eat. Still another emigrated from Mexico. Youcould barely hear a pin drop as she told the story of the coyote who guided herfamily across the border.

As we went around the room and sharedour stories, a knot began to form in the pit of my stomach. Icompared myself to the others. Id grown up in a middle classfamily. My parents were still married. We always had enough foodand Id had the best education they could offer. I took tennislessons and piano lessons and spent summers on vacation. There wasno doubt Id lived a privileged life. I felt lucky to have beengiven so much and I was grateful for all of it. Still, the pain myclassmates shared lent a richness to their experience, a depth Ilonged for. I found myself embarrassed, as though the financiallyabundant life Id led disqualified me in some way.

I neednt have worried. Although Icouldnt see it at the time, I too had my own share of pain. Hiddenbehind the almost perfect faade was a truth my family would notallow and did not recognize. Facing the whole of my own life wouldgive me all the lessons I would need. Clearly, I didnt know what Ididnt know.

Over the years I have been challengedby my tendency to see only what I wanted to see. I was taught to begrateful for what I had. To focus on what is comfortable. It wasnteasy to say the unpopular thing, to stand alone in my truth. Likemost of us, I wanted to be liked. To be accepted. In my own familyId often chosen to apply a thick layer of whitewash to cover overthe deep cracks and sharp edges, to ignore the hardships, thestrife and the difficult relationships. The truth was, there wereplenty of good things to focus on and I had been taught toappreciate them all. But ignoring the difficulties can make thegood things seem shallow and the experience feel like alie.

When my brothers, sister and I werechildren, my parents would take an annual Christmas card photo. Ona fall day in late October, when the leaves were just beginning toturn orange, red and golden yellow, wed dress in heavy woolsweaters and puffy parkas, don mittens and caps and gather aroundthe blue spruce in the front yard. Wed smile as my father snappedphoto after photo, pictures to be used for the homemade Christmascard my mother sent out each year. After my father finisheddeveloping them in his dark room in the basement, my mother wouldpick the best one and send it out to our family andfriends.

But behind that carefully craftedimage was another story. We hated taking the annual Christmas cardphoto. For one thing, it took hours. My mother arranged andrearranged our position around the tree as my father took dozensupon dozens of photos. The fall air was thick and we sweat underour winter clothing. As we shifted our bodies around the tree andtugged at our itchy wool sweaters, my mother criticized the way wesmiled. She chided us for closing our eyes at exactly the wrongmoment. Afraid to speak up, we swallowed our anger only to have itleak out when one or another of us began to cry. And yet, yearafter year, their friends commented on what a wonderful photo itwas.

It took a long time for me to have thecourage to see what I did not see back then. What I could not allowmyself to see. Behind the representational circles and squares ofthe genogram, behind the faade of a middle class life was thestruggle to be seen, to make a connection that all the money in theworld could not buy. Although my genogram lay out the structure,the real work was just beginning.

A year after my mothers death, I satin the living room of my friends house, tears streaming down myface. I felt knotted up inside, threads of grief, shame, guilt andsadness twisted around my heart. I was overwhelmed by her loss andI did not understand why, even after she was gone, I still clung tofeelings about her that no longer served me. I wanted to understandwhy Id struggled so with my mother. Why the hollow ache in myheart would not go away. Why I wanted her acceptance so desperatelyand why I felt so powerless to do anything about it. And so I beganto write.

Although I have traveled this roadwith hundreds of families, it was not until I chose to do it myselfthat I could learn the lessons I needed to learn. As I peeled backthe layers of my own life, I began to see things I had not seenbefore. I was forced to confront family myths that Id always heldto be true. I discovered that what Id believed to be the wholetruth of my family story was only partially true; that there werethings I chose not to remember. Stories that had been readilyaccepted. Patterns of behavior that were destructive and challengedthe image of the idyllic family life I remembered. Until I beganthis journey, I could not see the role Id played or the way thedecisions I made so long ago still impacted me.

Now I share those stories with mystudents. My classroom is filled with people from all walks oflife, people who come from families who are every bit as diverseand unique as the other. As I tell them stories about my own life,I encourage them to share stories of theirs. To ask questions, tobe curious, to learn to speak their truth. Stories, I tell them,have the capacity to connect us, to bridge the divides we feel andallow us to understand. As my students share their stories, theybegin to accept one another and as many times as I watch it happen,it always feels like magic. Because no matter how different weappear on the outside, inside we are all human.

Next page