A re you serious?

Are you sure?

How can you tell?

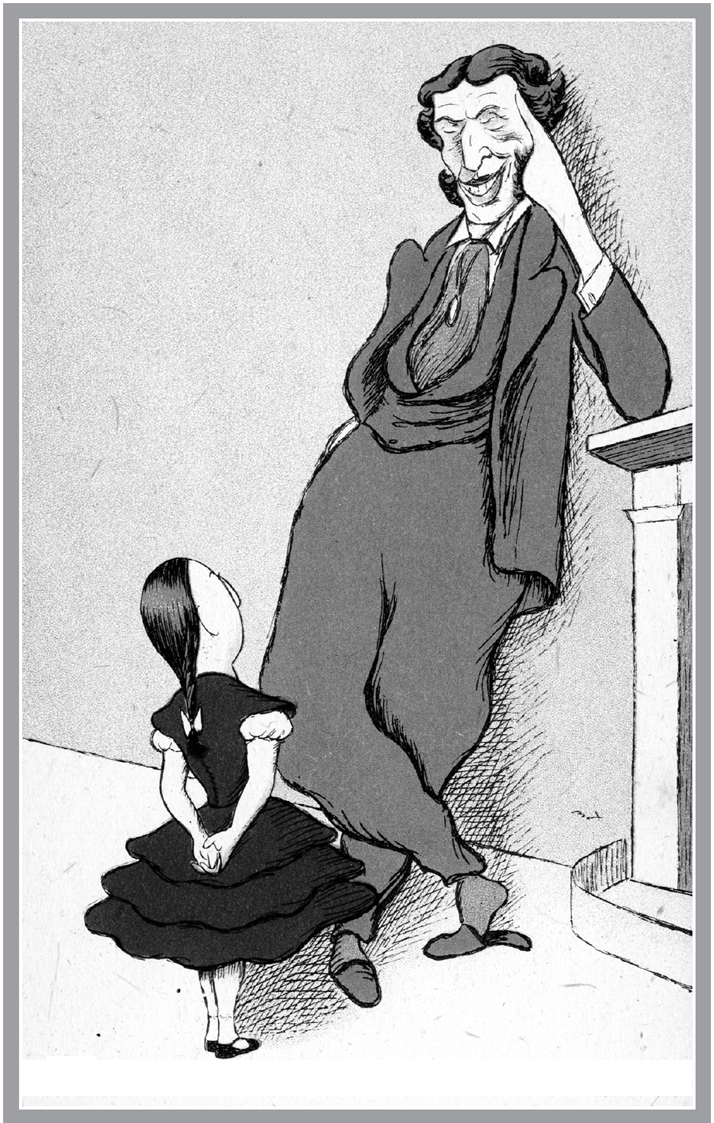

In 1904, the British humorist Max Beerbohm published a cartoon about his distinguished countryman, the poet and social critic Matthew Arnold. It depicts the renowned literary man leaning against a mantelpiece, one leg crossed in front of the other. Standing before him, her braid tied with a white bow, and attired in a red pinafore dress, is his tiny niece, Mary Augusta. She is looking up at her famous uncle. Arnold is wearing house slippers and has lifted his right foot up at the toes so that the rest of his foot lolls, mischievously, out of the slipper. He is smiling mischievously, too, with amusement and a hint of derision as he listens to the young girl. The caption has her asking: Why, Uncle Matthew, Oh why, will not you be always wholly serious?

The meaning conveyed by Beerbohms satire is part of the story told by this book. But before we can understand Beerbohms cartoon, we have to understand Arnolds idea of what he called high seriousness.

Matthew Arnold was considered one of the wise men of his age. In essays and books that he published throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, Arnold established his authority by developing a single powerful insight. Understanding that religion was under siege by Darwinist ideas and the forces of science and technology, Arnold prescribed a substitute for the waning faith in God. He called it high seriousness. Seriousness, Arnold believed, was the modern persons soulfulness.

Just as the church had been the seat of faith, Arnold located high seriousness in culture, poetry in particular. For Arnold, poetry was the supreme aesthetic achievement, and the essential condition, he wrote, for supreme poetical success... [was] high seriousness. He was nevertheless pretty vague about what high seriousness consisted of, saying only that it had to be a criticism of life. But Arnolds readers, steeped in religion and pained by its decline, knew exactly what he meant. They understood that high seriousness was the secular equivalent of religious belief.

This moral perspective was what Arnold meant by criticism of life. He was thinking of the content and tone of the Bible. He might have had in mind Pauls lines in the First Letter to the Corinthians: When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face. The idea that, spiritually, adulthood is an incomplete phase of human development is a criticism of the way the worldly pressures of self-interest and practical necessity may cloud our perception of the truth. In Arnolds eyes, literature attained high seriousness when it offered just such sensitivity to the ways life fell short of its potential fullness. And like religious sentiment, high seriousness had to be expressed with what Arnold called absolute sincerity. Seriousness implied a trustworthy personality, just as faith in God once implied a trustworthy soul.

Arnolds conversion of religious sentiment into culture and taste held a special appeal for Americans. The high seriousness of high culture was just right for a country that lacked the rich artistic and intellectual heritage of Europe and frowned on impractical conceptualizing. Reading Arnold made the American businessman feel elevated; it inspired the American artist and intellectual to feel less alienated. Most consequential of all, Arnolds belief in arts salutary effect on morality was just right for a country whose exuberant capitalism, unrestrained by custom or convention, wasalong with science and technologywearing away the influence of religion.

Yet Arnold had nothing to say about seriousness in life. For him it abided only in culture. He made no room for the ultimate seriousness of the firefighter or the policeman, for the seriousness of the doctor, scientist, parent, teacher, friend, or lover. Nor did he embrace the seriousness of practical matters. I wonder what Arnold would have made of one contemporary businessman saying to another about a third man, Hes a serious guy. By that, the businessman means the man he is referring to is someone absolutely sincere about satisfying the interests of the people he does business with, or about sticking to his word, or about following through on what he sets out to do.

None of the forms of seriousness that are found in everyday existence has anything to do with high culture. But they are serious nonetheless.

There is another deficiency in Arnolds exaltation of high seriousness. He left out the importance of levity. Arnolds exclusion of wit or fun as an essential element of seriousness is what Beerbohm was getting at in his shrewd little cartoon. Beerbohm regarded Arnold as, in fact, more serious than the latters solemn notion of high seriousness let on. In Beerbohms depiction, Arnolds seriousness itself drew its power and sincerity from inner reserves of irony and mischief. Without the leavening presence of wit, Beerbohm seems to be saying, seriousness is merely the performance of seriousness. Only a child would be silly enough to expect seriousness to be always wholly serious.

But Beerbohm was expressing something even more important. Don DeLillo captures it well in his 2010 novel, Point Omega . Why is it so hard to be serious, asks one of the novels characters, so easy to be too serious? Beerbohm recognized that there exists a point at which seriousness stales and needs to be refreshed by new experiences and new insights. There comes a moment when what is considered serious by culture and society has to give way to a new seriousness or it tips over into a caricature of itself. The harder it becomes to be serious, the easier it is to be too serious. Seriousness then declines into the silly impersonation of seriousness.

Which brings us to our contemporary American life. Like Arnolds fellow Victorians, we also yearn for the ballast that religion once provided. But instead of religious faith, we now say that we are searching for meaning . In our daily lives, being serious is the equivalent of living meaningfully.

It is extraordinary how frequently the words serious and unserious are now used as moral categories. Serious and unserious have become the critical antipodes by which we navigate through our days: serious is the highest praise, unserious the worst insult. President Obama was elected, even by people who did not share his political values, because he was widely believed to be a serious person who honestly addressed the bare facts. I supported Obama because I thought he was a serious man, declared the conservative writer Christopher Buckley. Under the headline A Hero for Our Time, an absolutely sincere Garrison Keillor wrote in the Los Angeles Times that during Obamas campaign Americans realized that we were done with the flummery and balloon juice, and the country saw its new president: a serious man for serious times. The eloquent Obama himself sometimes displayed his seriousness in Arnoldian fashion, using it to express a criticism of life in old-fashioned religious terms. We remain a young nation, he said in his inaugural address, but in the words of Scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things. His detractors use the same criterion to evaluate him. He was not serious, declared Peggy Noonan about Obamas January 2011 State of the Union speech. The Columbus Dispatch likewise pronounced the speech breathtakingly unserious.